A haunted Vietnam vet finally looks back in order to move ahead

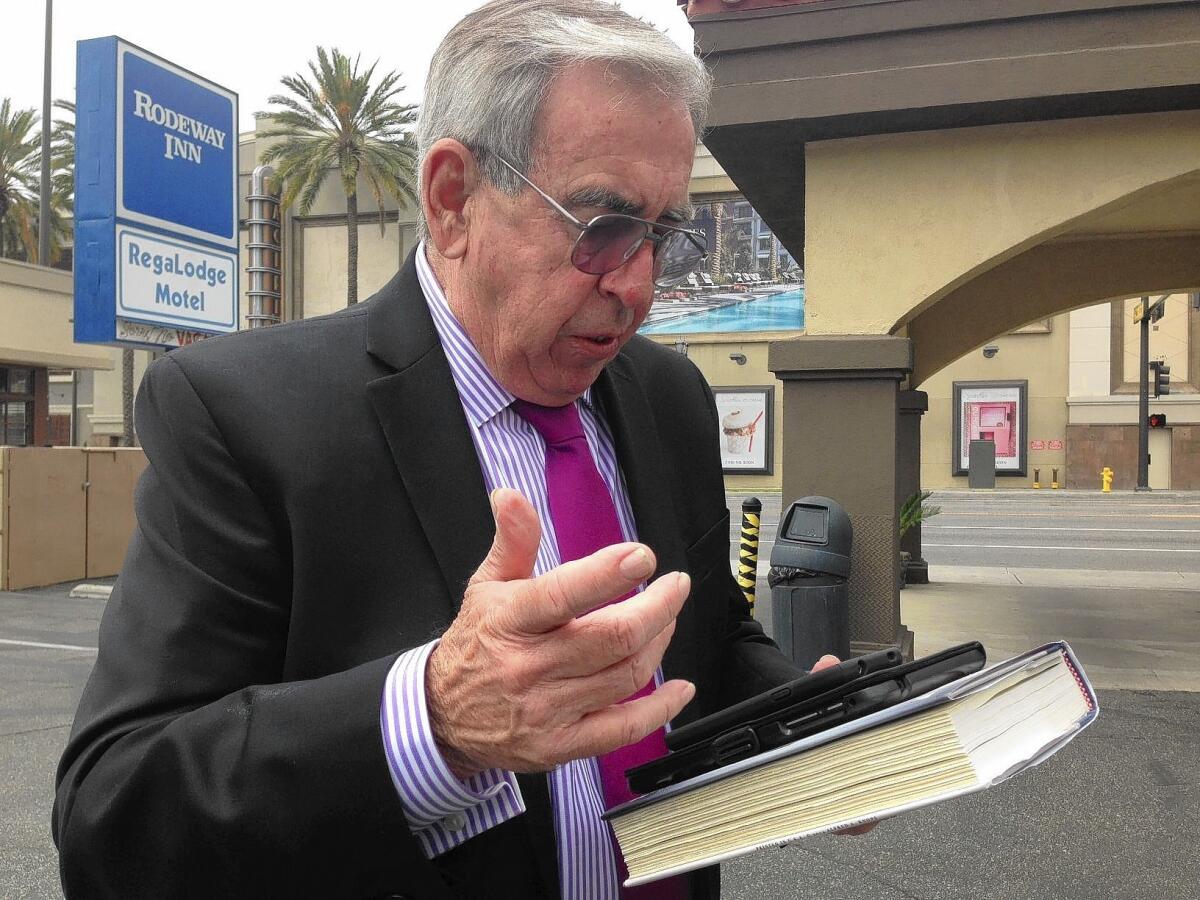

For nearly two decades, Rick Ramage lived in a Redondo Beach bicycle shop owned by his longtime buddy. Both were Vietnam veterans. But Ramage, a Marine with H Company, 2nd Battalion, 5th Regiment, didn’t like talking about his tour of duty — particularly not the events of late 1967, when he was squad leader of a kill team in Quang Nam.

After the war, Ramage dealt with the past the way many veterans do. He left it there, as best he could.

But he drank too much, lost a job and a wife, and at times, even his will to go on.

Once, he put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger.

“It had a broken firing pin,” Ramage says.

Another time Ramage, now 68, tried taking his life with prescription drugs. On another occasion, he laid out his dress blues and prepared again to end it all, but that attempt was thwarted when someone came by to check on him. When he lost almost everything and had nowhere to go, he began working in the bike shop and sleeping on the floor after closing time.

Some veterans of the Vietnam War became politicized in one way or another, either defending the cause for which they sacrificed or speaking out against the massive human cost of what was arguably an ill-conceived campaign from the beginning.

Not Ramage.

“I was just doing a job,” he says of his service, and he was content to leave political analysis to others as he tried to get on with his life.

Once a Marine, always a Marine, Ramage says. So he didn’t talk about the nightmares, the guilt, the regret, the shame, the pride or the grief. He gave some of his medals, including two Purple Hearts, to friends or relatives, along with a piece of shrapnel removed from his body.

It wasn’t until the bike shop closed a few years ago, and Ramage found a nonprofit housing and recovery program in Long Beach called U.S. Vets, that he began to consider the possibility that he might never move forward without first looking back.

“Someone in their 60s who’s been carrying it around for 45 years, not talking about it, keeping it contained, is going to do some damage,” said Todd Adamson, Ramage’s psychologist at U.S. Vets.

The natural instinct is to bury painful memories, Adamson said. But that only makes things worse.

As part of Ramage’s therapy, Adamson asked him to write about the very events he was trying to erase from memory. Reluctantly, Ramage pushed himself back to Quang Nam, when he was a 21-year-old kid from Glendale, and sketched out the details of the night that would haunt him for decades.

“At approx. 1600 on the afternoon of Dec. 19, 1967, Lt. Lambert … sent for me … and advised that he wanted me to take out a 6-man kill team that evening,” Ramage wrote in what is a chillingly dispassionate account of unimaginable carnage, as if he still can’t quite let himself feel and react to the events of that day.

Ramage’s squad hit a booby trap and a mine exploded.

“After making sure I hadn’t lost my foot I began to move towards my men to check for injuries,” Ramage wrote.

One “was gone from the waist down.” Another had lost an arm, and yet another took shrapnel between the eyes and was dead. Ramage went to the aid of a Marine screaming for help, reached under his vest to check his wound, and realized he’d just placed his hand inside the dying man’s chest.

“At this point I’m covered in blood…. I can taste, smell, and feel blood.”

Ramage and one other man in his squad made it out alive. In all, 12 Marines died that day in the same vicinity. Ramage was hospitalized, recovered and returned to combat, only to be injured again.

After writing his account of Dec. 19, Ramage was instructed to read it aloud every day for 30 days, as well as share it with others. None of that was easy, but he thinks it may have helped.

“It was hard to believe he had just been carrying that with him all these years,” said his son, Matt, who never knew the details of his father’s ordeal.

Ramage’s drinking and depression landed him in a VA hospital more than once, but because of bureaucratic bungling and his own inaction, he did not begin receiving disability benefits until a few years ago. He was recently upgraded to 100% disability pay for PTSD, traumatic brain injury, depressive disorder and physical wounds.

At a time when the VA is under the spotlight for scandalous delays in treating veterans, one can only wonder if Ramage might have endured less hardship over the last few decades if he had either received or demanded more care. But he isn’t one to point fingers or ask for sympathy.

His struggles are far from over, but in June he’s moving out of U.S. Vets into his own place. To begin this Memorial Day weekend, he took a train to Glendale to watch his granddaughter graduate from high school with honors. And in August, he plans to attend an H Company reunion and see the lieutenant who sent him on that mission in 1967.

“Rick was very cool under fire and had a lot of maturity for his age,” Michael Lambert, himself a Purple Heart recipient, told me by phone from Georgia. “He was a good leader but also very concerned for his men.”

It’s a humbling experience, talking to men like Lambert — who has triumphed over his own demons — and Ramage. After they’d told me their stories, I could think of only one thing to say to each of them.

Thank you for your service.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.