Downtown L.A.’s private City Club strives to attract younger members

Born in reaction to other private clubs, the City Club recruited women and minorities and touted its diversity. Now it hopes to bring in more people under 50.

Just before his 40th birthday, Todd Seligman got an invitation into a world where he was certain he didn't belong.

"Why don't you come down?" the woman on the other end of the line asked. "We'll give you lunch and show you the club."

The locale in question was the City Club, a members-only spot downtown. The kind of place with dark wood paneling on the walls, waiters who address you by name as they refill your coffee and men in suits. Seligman was a former pro BMX biker who produced action-sports videos and showed up to work most days in jeans and a Volcom hoodie.

"I was like, 'private club?' " Seligman said, scrunching his upper lip toward his nostrils like he'd just smelled something rotten. "But then I was like well, whatever. Free lunch? OK."

At first glance he saw the hints of old money he expected when he initially called to find out about booking a space at the club for his birthday. But then he noticed a few other things: its easy vibe and diversity. There were purse hooks at the bar, and not everyone was white and nearing retirement age.

He wanted to come back sometime and bring his wife.

But when he pitched the idea to Sian — a thick-framed-glasses-and-bright-red-lipstick-wearing urban farmer — she shot back: "You know I'm an Asian woman, right?"

The BMX biker and the urban farmer. The most unlikely members, they thought, and yet, a couple of years later, they spend three or four days a week at the club, shelling out $280 a month for a membership that doesn't even include a gym.

They used to call them "gentlemen's clubs," places where the who's who of (white male) Los Angeles rubbed pinstriped shoulders. Even today, two of the oldest private clubs in the city, the Jonathan Club and California Club, have a no-jeans policy. But in the 21st century, as the economy tanked and start-ups changed what wealth looks like, some in the old guard realized that they needed to change.

Like its counterparts, the City Club fell on hard times during the recession, even though it had already tried to diversify beyond the white male base. In 2011, when Westwood's members-only Regency Club closed its doors, City Club General Manager Larry Ahlquist took it as a reminder of how hard the club would have to fight for relevance.

He knew that the old club had too much dark wood to lure younger members. He compared it to the tchotchkes and old smell of Grandma's house.

They had to kick the stuffiness to get a new kind of diversity: age.

A visitor is seen through the frosted door from inside the City Club. More photos

The City Club got its start at the tail end of the go-go 1980s building boom in downtown. Every year, it seemed, a new mirrored monolith popped up on Bunker Hill or in the Financial District. A bank. A law firm. Another bank. And every new building brought with it an extra skyscraper full of briefcase-carrying suits.

It was an elite world, and one already catered to by the Jonathan and California clubs, which opened in the late 19th century.

They had a 100-year head start on the City Club and a legacy as the hideaway of L.A.'s power players. But they also had recently tarnished reputations, the result of membership restrictions that sparked legal and political battles. So when the City Club opened in 1989 — a few years after the other spots had started to admit women and African Americans — it branded itself as a hub of diversity.

In a story that ran a few months after its opening, a Los Angeles Times writer described the City Club as a place that "touts itself as a little United Nations among private clubs." About 17% of City Club's members were women that first year, according to the piece, which pegged the Jonathan Club's female membership at 3% and said the California Club didn't disclose the figures.

Since then, corporate downtown has slumped. A series of mergers and consolidations in the 1990s and 2000s brought the exodus of big businesses like Security Pacific Bank, First Interstate Bank and ARCO. A different downtown emerged, a go-to spot for foodies, artists and after-work tipplers.

"I mean, 5 o'clock and there wasn't an asset in L.A," Ahlquist said of the downtown he remembers from 20 years ago.

It was time to change. First up on the agenda: Move from the dark paneling of the Wells Fargo Building on Bunker Hill to the walls of glass on the 51st floor of the City National Bank Building.

Todd and Sian Seligman join City Club General Manager Larry Ahlquist, right. More photos

As the elevator makes its way from the first floor to the 51st, your ears pop, reminding you, it seems, that you're not going to the club, you're traveling there. The doors slide open and soft jazz fills the atrium. A brunet with her hair in a neat bun greets you with an easy smile. She's the Director of First Impressions. And then there's Ahlquist, wearing a pinstripe suit and peering out the floor-to-ceiling window.

"You can see the ocean where it starts to glimmer," he says, lifting his eyebrows like an exclamation point.

He zips down a hallway past a room with wallpaper that looks like graffiti. It's for when you need to think outside the box, he says. On the other end of the club, a 138-inch flat-screen TV, which hangs above a shuffleboard, plays CNN in the mornings. In the evening, it turns into a bar — one with Eagle Rock Brewery beers on tap to cater to a generation that treats beer like Ahlquist's treated wine.

"I remember when ... a premium beer was Michelob," he said. "One of my favorites is Heineken, but you go in places now and they don't even carry them. Now they've got all these different craft beers."

After stopping to chat with a member visiting from a sister club in Seattle, Ahlquist makes his way through a doorway and into a dining hall with tiny bonsai trees on every table. It's called the Arbor Room and it's the only place in the club where you can't wear jeans and a jacket is still required.

The City Club ditched its more buttoned-up dress code for a (mostly) denim-friendly one recently, Ahlquist said, because now even the founders of booming companies wear jeans to work.

"All the dot-com places," Ahlquist said. "The cool places."

The club has a Twitter account, which it uses to send out pictures of a young, tattooed DJ who sometimes spins at the bar (granted, at the not-exactly-clubbing hour of 6 p.m.). It also has a Facebook page, where it punctuates posts with "#loveourmembers" and promotes its catchily named social media seminars: "All About Twitter" in February and "Power of Pinterest" in March.

It has also implemented age-based discounts. A membership package that a 50-year-old would pay $345 a month for costs $208 a month for the younger-than-30 crowd.

The average member is in his (or her) mid-40s, Ahlquist said, skewing almost a decade younger than what was once the norm. Membership is at 1,227 now, he said, up from a low of 1,030 during the recession.

You're seen much more as having value than being some young whippersnapper."— Todd Seligman,

City Club member

Although some of the Seligmans' friends still give them a hard time — using air quotes and an accent that sounds vaguely British when they mention "the club" — the couple say the perks of the pricey fees are worth it for them.

For Todd, who works out of a warehouse, it meant he could stop renting the office he used for client meetings and conduct them at the club instead. And for Sian, who runs a company called Sow Swell out of their Eagle Rock home, it gives her a home base in downtown. It's a place for morning coffee and evening cocktails. A place to make connections and to be treated like someone worth making connections with.

"You're seen much more as having value than being some young whippersnapper," Todd said.

And, in a way, you're paying for prestige.

On a recent trip to Las Vegas, when Todd and his buddies couldn't find any restaurant with less than a two-hour dinner wait, he called ClubCorp, the City Club's parent company, to see if it had any connections in the city. It told him to head to Capital Grille, a fancy steakhouse on the Strip.

Visitors take in the view from the City Club. "You can see the ocean where it starts to glimmer," General Manager Larry Ahlquist says. More photos

When they showed up, the person at the door said there would be a wait. When Seligman mentioned his membership, the person cut him off: "Oh, I'm sorry, Mr. Seligman. Yes, right ahead."

Back on the bank's 51st floor a few weeks ago, the leaders of the City Club's myriad committees — next year Todd will lead the Wine and Spirits Committee and Sian the one in charge of social events — gathered in a ballroom that overlooks Staples Center.

The club's chef prepared a coddled egg with mustard sauvignon sauce and fried Brussels sprouts. The members took turns complimenting one another and offering toasts over the success of their grand opening at the bank tower a week earlier. Someone joked that the only thing that could have made the night better was more alcohol. Impossible, a woman shouted. Then someone else chimed in: "I already had a hangover."

Ahlquist laughed and took a swig of his Heineken.

Follow Marisa Gerber (@marisagerber) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

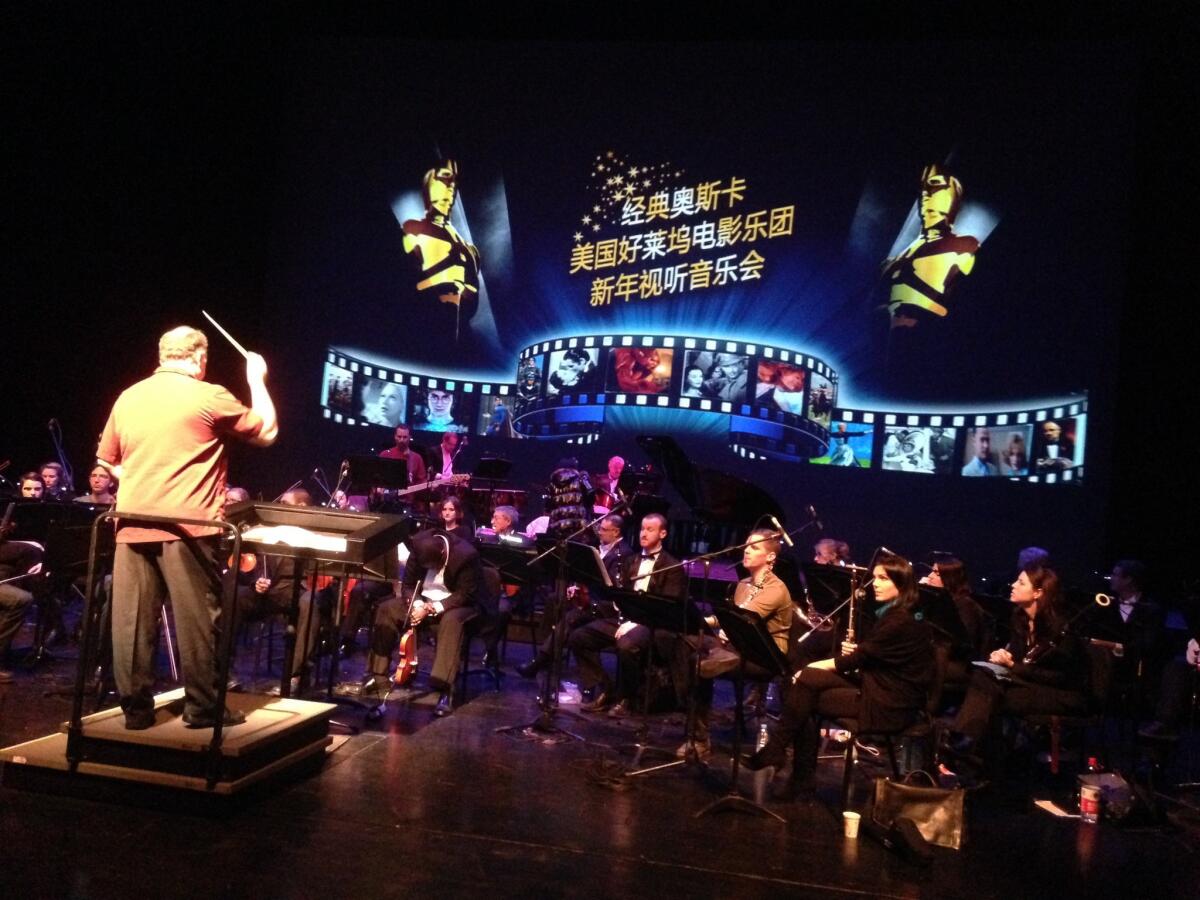

An atypical orchestra offers music for China's masses

When we got there to rehearse the day before, they were still building the bathrooms."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.