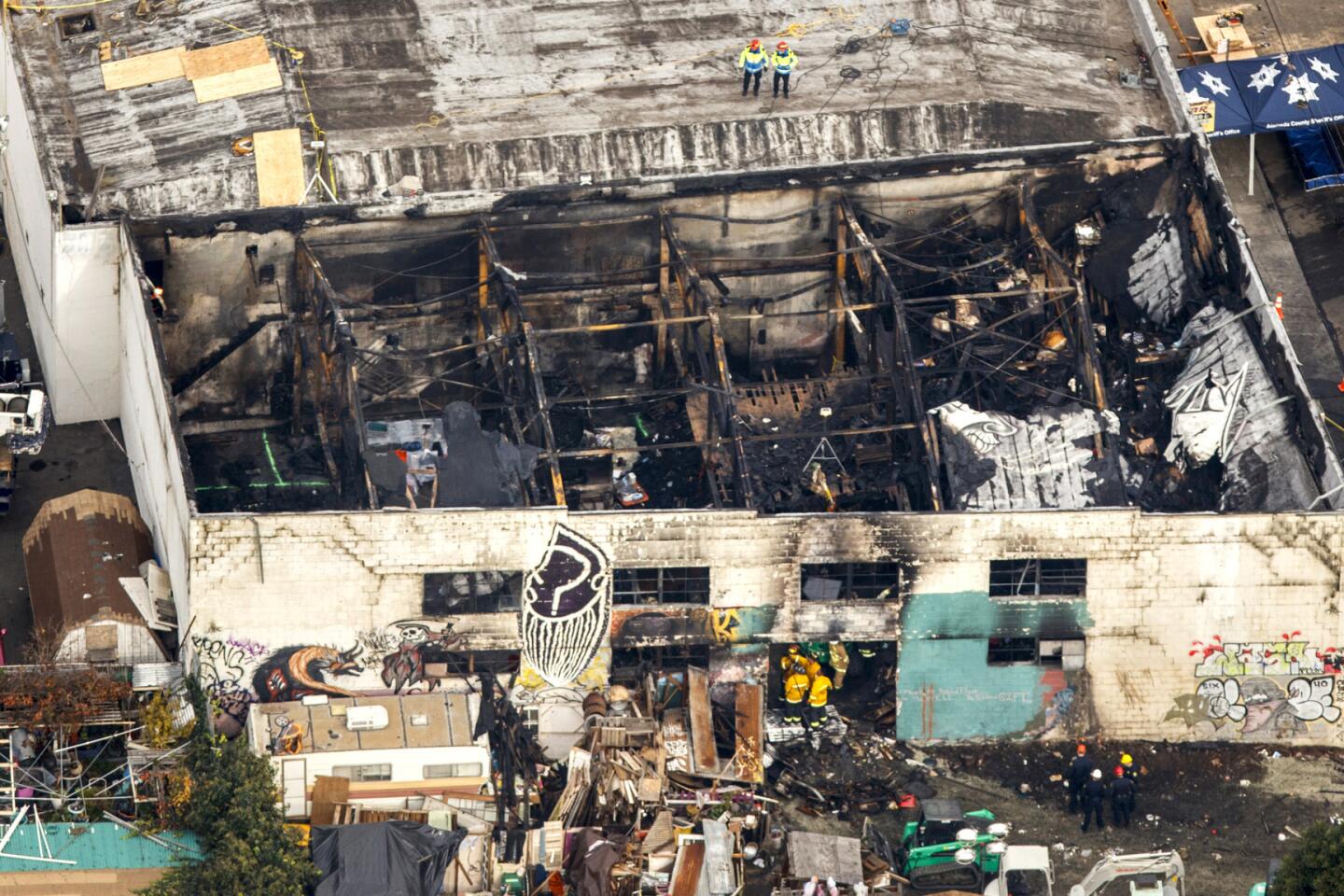

Oakland warehouse was a cluttered ‘death trap’ filled with pianos, RVs, but no fire sprinklers, former residents say

The Oakland warehouse where at least nine people were killed at a late-night concert was a deadly blaze waiting to happen.

People who previously lived there recalled a building that lacked fire sprinklers and had a staircase partly made of wooden pallets. Partygoers recalled a rabbit warren of rooms crammed with belongings — pianos, organs, antique furniture, doors and half-finished sculptures.

“It was a tinderbox,” said Brooke Rollo, 30, who did not attend Friday’s event but had gone to parties there previously.

Firefighters who responded to Friday’s blaze described the interior as a labyrinth. And an Oakland building official said organizers of the warehouse concert never obtained a permit for the event, preventing city workers from inspecting exits, fire extinguishers and other vital safety features.

Still, the nearly 10,000-square-foot building on 31st Avenue, known to many as the Ghost Ship, had been a subject of complaints well before Friday’s fire.

The city was contacted three times in the last two years about trash and debris piled up outside the warehouse. On Nov. 14, inspectors with Oakland’s Planning and Building Department began investigating an allegation of illegal construction inside the building.

Darin Ranelletti, the department’s interim director, said inspectors attempted to enter the warehouse three days later but failed to gain access.

Ranelletti said his department had also received reports that people were living in the warehouse illegally. Inspectors were still investigating before the fire broke out, he said.

The Oakland warehouse is one of several properties owned by Chor N. Ng, according to her daughter, Eva Ng, 36. She was adamant that the warehouse was being leased as studio space for an art collective and not used as residences.

Eva Ng said she had not been to the building for a year and saw no evidence someone was living there. She said she had been reassured by the lease holder that nobody lived in the building.

“They confirmed multiple times. They said sometimes some people worked through the night, but that is all,” Ng said.

Still, one former tenant told The Times that he remembered at least 10 people living inside the warehouse. Bradley Evans, who moved out in August 2015, said the man who collected the rent lived in the building with his wife and three children.

The man instructed tenants to tell the landlord they were working on art projects and not living there full time, said Evans, 21. The landlord “came by once a month to collect the money and didn’t ask any questions,” he added.

Shelley Mack, who lived in the warehouse from October 2014 to February 2015, said the building had no fire alarms or fire sprinklers. Five or six mobile homes were parked inside the warehouse and were rented out, she said. At one point, residents used “an illegal hookup” to get their electricity from the building next door, said Mack, 58.

“It’s a dump and a death trap,” she said.

Ng said she believed the building had smoke detectors and two second-floor exits, both wooden stairs. She was not familiar with a report by authorities and others who had been inside the building that one of the stairs was at least partly made of pallets. But she was aware that there had been parties in the building.

“It’s Christmas, after all,” she said.

The warehouse was leased to a collective, Ng said.

An organization housed at the venue called itself the Satya Yuga Collective, a group of artists and musicians who described themselves on social media as “an unprecedented fusion of earth home bomb bunker helter skelter spelunker shelters ...”

The collective had been run by a man who identified himself as Derick Ion. His wife, Micah Allison, declined to talk about conditions at the warehouse, including whether there was a sprinkler system and whether people lived there. She said she was focused on finding a hotel for the night and getting emergency clothing for her children.

“I’m not going to speak to anybody about that kind of stuff,” Allison said. “I’m going to have to speak to my lawyers before I answer any questions.”

Cities in California typically require a special permit for one-time-only events — such as weddings, art openings and concerts — in buildings not constructed for such activities, said development consultant Hamid Behdad, who supervised L.A.’s effort to convert commercial buildings to lofts and apartments.

To secure those permits, an owner must show fire and building inspectors where the exits are, the locations of the fire extinguishers and how the building will be illuminated in case of an emergency, he said.

Behdad also said the state’s building code prohibits the use of wood and other combustible materials for staircases in buildings that stage events with more than 49 people, he said.

“Wood stairs, my God,” he said. “Any way you look at, this was a recipe for disaster.”

Photos on the warehouse’s Tumblr page show a maze of rooms, with walls and dividers made from pianos, boxes, salvaged doors and other materials. Wooden rafters were adorned with hanging lanterns, holiday lights, bicycles, stereo equipment and exposed wiring.

Ben Brandrett, a mental health researcher living in San Francisco, attended a performance at the warehouse about seven or eight months ago and noticed that a staircase didn’t have a banister.

“I remember thinking, ‘This seems sketchy,’” he said.

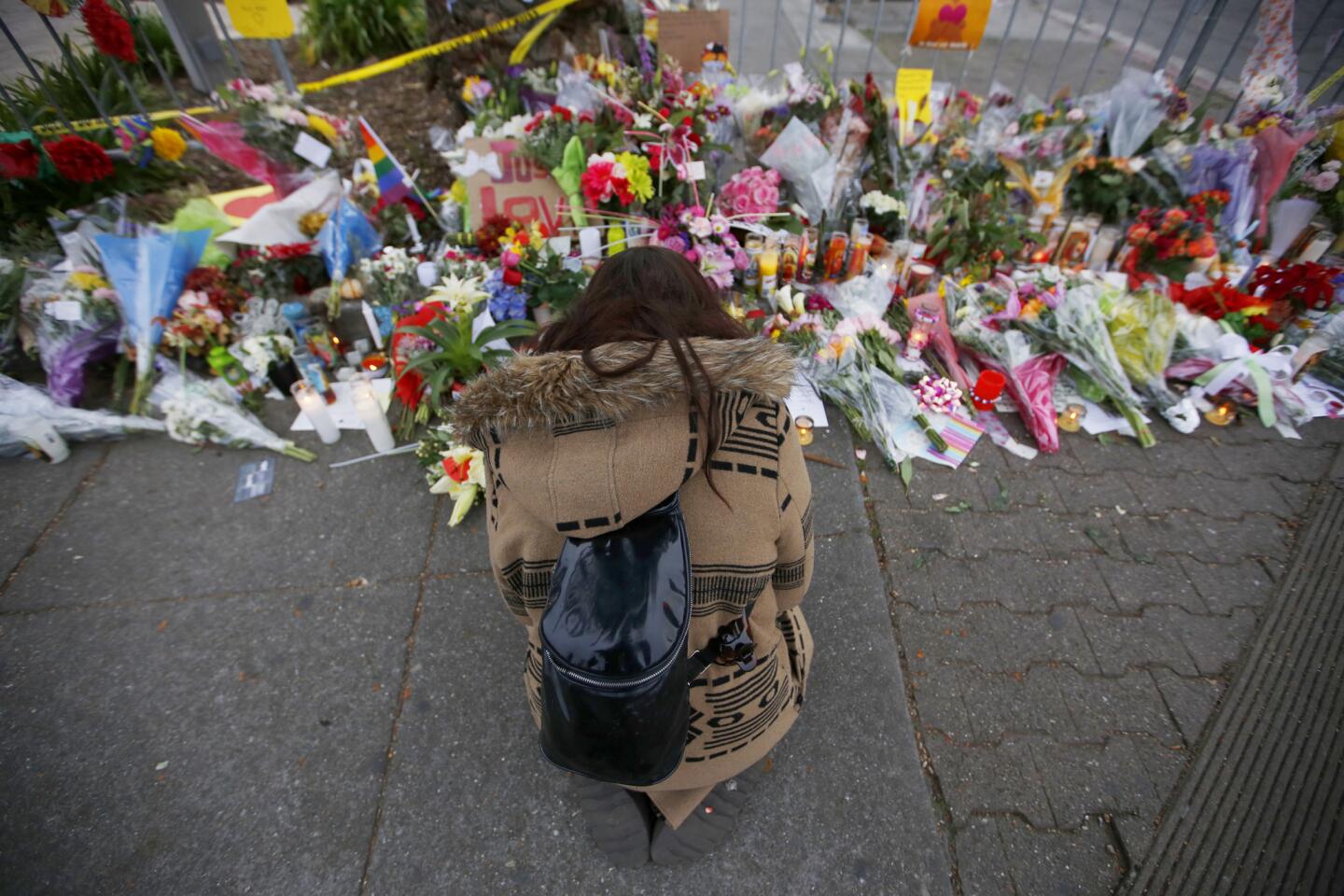

Members of Oakland’s artist community said they were devastated by news of Friday’s fire. Rising real estate prices, they said, have pushed many artists out of San Francisco and into the East Bay. Now, some are struggling to stay in Oakland, they said.

“It’s increasingly difficult for artists to pay to live here,” said a 31-year-old performance artist who goes by the name Lichen. “In order for us to create, sometimes we have to do it in places that aren’t the most ideal or safe.”

Oakland City Councilman Noel Gallo, who represents the district where the fire broke out, said he had been hearing complaints from constituents about debris outside the warehouse. Asked if the building had permits for people to live there, he said: “Absolutely not.”

“The reality is, there are many facilities being occupied without permits,” he said. “They’re occurring on Oakland’s streets, especially in neighborhoods like mine.”

Times staff writers Gale Holland, Paige St. John, Russ Mitchell and Tracey Lien contributed to this report.

ALSO

A look at some of the deadliest nightclub fires

Live updates: Officials prepare for more fatalities in Oakland fire

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.