Sydney Brenner, Nobel Prize winner who helped decipher genetic code, dies at 92

Sydney Brenner, a multitalented biological giant who helped decipher the genetic code, discover how its information is put to use and laid the groundwork for DNA sequencing technology, has died at the age of 92.

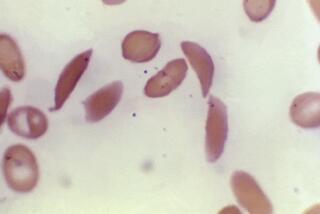

Brenner, who died Friday in Singapore, was also famed for research on a tiny worm, Caenorhabditis elegans, which became a model organism for studying animal life. Many of its genes turned out to have human equivalents, leading to insights into human biology.

For the C. elegans research, Brenner, John Sulston and Robert Horvitz shared the 2002 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. It also earned Brenner an informal title he didn’t much care for: father of the worm.

Brenner’s seven-decade career spanned the globe, and he was active in science until the end. He spent the last part of his life in Singapore, where he advised that country on its biotechnology policy.

The South African native also performed research in Britain and San Diego, where he served on the faculty of the Salk Institute, which he joined in 1976, and Scripps Research. Brenner’s research led to the formation of several companies, including the San Diego biotech Combichem.

“He was one of the most important figures in molecular biology for the last 50 years,” said genome expert J. Craig Venter, who knew him for decades. “There wasn’t a major breakthrough in the early days that he didn’t play some role in. He was a walking history of the whole field.”

Venter said that while the worm research was significant, it was far from his most important contribution to science.

Venter said Brenner’s work on the genetic code was fundamental. He teamed up with scientists led by Francis Crick, who with James Watson discovered the double-helix structure of DNA.

In a 1961 paper, the team outlined the “triplet” code by which DNA spells out the instructions for proteins. A sequence of three DNA letters specifies one of 20 amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, along with a “stop” sequence signaling that the protein is complete.

Certain three-letter sequences are redundant, spelling out the same amino acid. Scientists at Scripps Research led by Peter Schultz took advantage of that redundancy to engineer bacteria that produce a 21st amino acid, giving it the power to make proteins not found in nature.

In related work, Brenner helped discover messenger RNA, the carrier molecule that copies the DNA code and carries it into the cell for protein synthesis. The discovery of mRNA led to development of “antisense” drugs by Carlsbad’s Ionis Pharmaceuticals. These drugs intercept mRNA to block or alter protein production.

Later on, Brenner’s discoveries became the basis for what is known as “next generation sequencing,” which offered greatly improved speed over existing technologies. It combines reading multiple copies of DNA in parallel with repeated sequencing to reduce errors.

The technology was used in a company he co-founded, Lynx Therapeutics, which was acquired in 2005 by Solexa. In 2007, Illumina purchased Solexa, making its next-gen technology the core of its products.

At Scripps Research, he collaborated extensively with Richard Lerner, its former president, and faculty member Kim Janda, among others. CombiChem, the San Diego biotech, was founded by a team including Janda and Scripps Research colleagues Dale Boger and Chi-Huey Wong.

Janda, a chemist, said Brenner was a close friend to his family and mentor since they met three decades ago.

In 1992, Brenner and Lerner proposed a method in molecular synthesis that employed a “bar code” tag that precisely described the steps used to create each molecule.

The method married DNA with combinatorial chemistry, a way of rapidly making many kinds of molecules in vast quantities. The DNA, added step by step in the synthesis, served as the tag. So when scientists found a rare “hit” in a molecule, they didn’t have to figure out how it was produced.

That proposal was ahead of its time. But genetic technology has matured since then, partly due to Brenner’s own work on DNA sequencing. This method of making DNA-encoded libraries is now used by drug companies as a way of cataloging the vast numbers of molecules they work with, so the rare “hits” can be easily replicated.

“Everybody uses DNA-encoded libraries today,” Janda said. “And that’s something Sydney came up with.”

Born in Germiston, South Africa, in 1927, Brenner earned degrees in medicine and science in 1947 from Johannesburg’s University of the Witwatersrand, the Salk Institute said in a biography. Brenner moved to Oxford University in 1952 to pursue his doctorate in physical chemistry.

While at Oxford, he became engrossed in DNA and developmental genetics research. He joined the University of Cambridge in 1956 and shared an office with Crick for nearly 20 years.

Brenner’s co-discovery of messenger RNA led to his first Lasker Award in Basic Medical Research; he later received a second Lasker Award in honor of his outstanding lifetime achievements.

“We all owe much to Sydney. With his passing, we have lost a great scientist and a good friend,” said Salk professor Terrence Sejnowski, holder of the institute’s Francis Crick Chair.

Brenner is survived by his children, Belinda, Carla and Stefan. His wife, May, died in 2010.

Fikes writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.