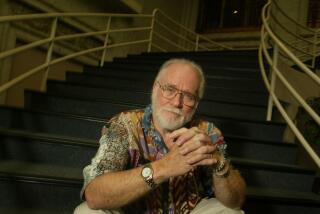

Theodore Bikel dies at 91; actor, singer and activist

Actor, singer and activist Theodore Bikel grew up in a second-floor apartment in Vienna where the family book collection included a 20-volume complete works of Yiddish storyteller Sholem Aleichem.

In 1938, the family fled the Nazis, leaving almost everything behind. But the words and spirit of Aleichem, whose works were the basis of the musical “Fiddler on the Roof,” followed Bikel the rest of his life.

“I find as time goes on,” Bikel said in a 2014 documentary, “that I am walking in his shoes, as a man, as an artist, as a Jew.”

Bikel, whose prolific, wide-ranging career included playing the lead character Tevye in “Fiddler” more than 2,000 times onstage, died Tuesday at UCLA Medical Center. He was 91.

He died of natural causes, said his longtime agent, Robert Malcolm.

Bikel was often cast in roles that required accents, and he had an extraordinary variety of them to call upon. In the 1951 film “The African Queen” he was a German boat officer, and he originated the part of Captain von Trapp, an Austrian, on Broadway in 1959 in the musical “The Sound of Music.”

But Bikel’s breakthrough stage role in London was in the 1949 production of “A Streetcar Named Desire,” and he was nominated for an Oscar for playing Southern sheriff Max Muller in the film “The Defiant Ones,” directed by Stanley Kramer.

“I said to (Kramer), ‘I’m not a Southerner. I wasn’t even born in America,’” Bikel said in an 2006 interview with the Montreal Gazette. “He said, ‘A good actor is a good actor is a good actor.’ I’ve never forgotten it.”

In a film and TV career that spanned half a century, Bikel racked up more than 150 credits. In “Murder She Wrote” alone, he played — in separate episodes — an Amsterdam police inspector, a Soviet trade representative and an Italian opera star.

Other shows in which he appeared included “Star Trek: The Next Generation” (as the Russian adopted father of a Klingon boy), “All in the Family,” “Columbo,” “Mission Impossible” and “Dynasty” (for a reoccurring role that required an upper-crust British accent).

Bikel didn’t mind that he had no familiar persona as an actor. “Some actors are what they are no matter what name you give them,” he told The Times in 1988. “Clark Gable looked, walked and talked exactly the same in every picture. I like to change shape, accent and gait.

“That way I never get stale.”

Around the world he is probably most identified with “Fiddler,” which he first played in 1968 in Las Vegas at Caesars Palace. It was not the first time he played an Aleichem character — in 1943 at age 19, he had a small part in the play “Tevye the Milkman” in Tel Aviv.

For the musical, Bikel based his performance as Tevye — who sings of traditions and famously rails at God at times — on his real-life grandfather. “He was observant, pious, irreverent, contradictory, irascible,” Bikel told the Boston Globe in 1994. “He didn’t just talk to God. At times, he went Tevye one step further and stopped talking to God.”

From the truncated, twice-a-day version of the show he did in Las Vegas for several months, Bikel began touring with the full show, garnering standing ovations. Outspoken as ever, he criticized the original star of “Fiddler,” Zero Mostel, for engaging in improvised shtick.

“I don’t do this as a star-turn,” Bikel said in a 1995 Times interview. “Obviously, Tevye is a star role. But I take a back seat when I think it is proper to do so. You must let other people shine and have their moments.”

About five years ago Bikel finally stopped doing the musical, but he was not through with Aleichem. He continued performing his one-man show, “Sholem Aleichem: Laughter Through Tears,” and he developed the documentary “Theodore Bikel: In the Shoes of Sholem Aleichem.”

Drawn in part from Aleichem’s unfinished autobiography, the show aimed to present more of the writer’s sense of tragedy than is in the musical. “If the truth be known,” Bikel said of “Fiddler” in a 2008 interview, “it’s a charming show. It’s a nice show. But it is what my wife calls ‘shtetl lite.’ “

Bikel was born May 2, 1924, in Vienna and named for Theodor Herzl, a founder of the modern Zionism movement that advocated for the establishment of a Jewish state in what was then Palestine. When Bikel was 13, he peeked through drawn curtains to see crowds cheering the arrival of Adolf Hitler.

The family fled to Palestine — Bikel worked on a kibbutz and joined the Habima Theatre in Tel Aviv. Outspoken even then, he complained after a year and a half that he was not getting substantial roles. “Either I have talent or I don’t,” he wrote to the theater board. “If I don’t, why do you keep me hanging around?”

They didn’t. He left with colleagues to start their own small company. Then he moved to London, where he studied at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts. Lawrence Olivier, who directed the 1948 London “Streetcar,” cast him in the play, after which Bikel was in Peter Ustinov’s play “The Love of Four Colonels.” John Huston was in the audience one night, and picked him out for a part in “African Queen.”

Moving to the United States, Bikel not only acted, but had a career singing folk songs in more than 20 languages. He performed with Pete Seeger and in 1963 flew with Bob Dylan to Mississippi to perform at a voter-registration drive for African Americans. Dylan didn’t know it at the time, but Bikel quietly provided the money for his plane ticket.

Bikel was active in Democratic Party politics and was a delegate to the 1968 convention in Chicago where he participated in anti-war demonstrations inside and outside the hall.

He was also a staunch advocate for Israel, but at times protested that country’s policies regarding settlements in occupied territories.

And Bikel was active in union politics — he was president of the Actors’ Equity Assn. from 1973 to 1982.

He remained active as a performer into his 80s. “My curiosity is unabated, as is my joy in finding out things that I didn’t know before,” he told The Times in 2006. “I like living and experience.

“I even like the pain of living because it lets you know you’re alive.”

Bikel is survived by his wife, Aimee Ginsburg-Bikel; sons Rob and Danny Bikel; stepsons Zeev and Noam Ginsburg; and three grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.