The death penalty has long divided Americans. Here’s why those who oppose it are winning

A series of executions in Arkansas have reignited the long-standing battle over the death penalty.

Beginning last week, the state tried to put eight men to death over 11 days before one of the drugs it uses in executions expired. After legal challenges, half of the executions were blocked in court.

Yet, despite the high-profile executions in Arkansas — including the first double-execution in the nation in nearly 17 years — the use and support of the death penalty in the United States has steeply declined to levels unheard of in decades.

Capital punishment is still legal in most states. But, while activists and experts say it is far-fetched to expect it to be banned nationwide any time soon, they say the momentum against it is strong.

“Practically speaking, the death penalty is in its last days. But like any disease that’s rendered obsolete by modern medicine, it has a few flareups before the end,” said Eric Freedman, a law professor at

Here’s why.

Fewer people are being executed by fewer states

The number of annual executions in the U.S. hit a high of 98 in 1999. Last year, the number was 20. The last time it was that low was in 1991, when 14 people were executed.

If all the scheduled executions this year are carried out, 25 Americans will be put to death, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. The Washington-based nonprofit is critical of the death penalty.

Seven states have or are scheduled to carry out executions, according to the center: Texas, Virginia, Missouri, Arkansas, Ohio, Georgia and Alabama.

“It is a phenomenon now of a few counties in a few states,” said Freedman. “The vast majority of the country is living in counties where there hasn’t been an execution for decades.”

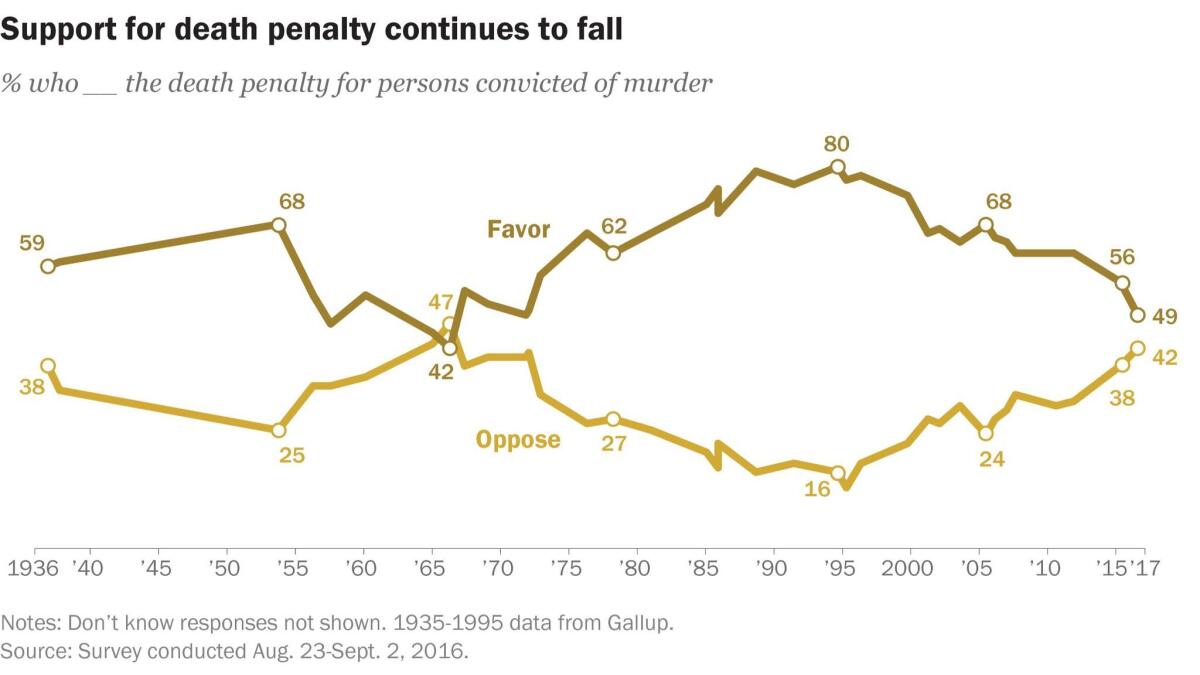

Public support is at its lowest level in 40 years

More Americans support the death penalty than those who are against it. But surveys over the years show that opposition is increasing and support is declining.

According to the most recent Pew Research Center poll, 49% of Americans support the death penalty for people found guilty of murder. At the same time, 42% of Americans are against it. The gap in part depends on political party. Only 34% of Democrats favor the death penalty, compared with 72% of Republicans.

Experts say the decline can be attributed to a variety of factors, including well-publicized cases of people who were sentenced to death and then exonerated.

One recent such case was in Delaware in January, when Isaiah McCoy, a 29-year-old on death row for murder, was released from prison after being found not guilty in a second trial.

“When people find out real people are sentenced to death even though they are not guilty, people start struggling to support executions,” said Rob Smith, director of Harvard Law School’s Fair Punishment Project, which has argued against the Arkansas executions, saying the trials of the men on death row were full of “legal deficiencies.”

Prosecutors are less willing to seek the death penalty — and jurors are less friendly to it

It’s not just that fewer people are being executed. Generally speaking, fewer people are being sentenced to death.

Death sentences hit a high in 1996, when 315 Americans were condemned to die, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. The decline has been steady since. Last year, 30 people were sentenced to death.

“The vast majority of prosecutors these days will never even seek the death penalty,” Smith said. One reason, he said, is that jurors are less likely to be sold on it. Life sentences without parole, Smith said, are seen as better options.

Some district attorneys and state attorneys general have gone a step further, promising to not push for death sentences.

One of them is Dist. Atty. Aramis Ayala of Orlando, Fla., who vowed last month not to seek the death penalty in her cases. “I am prohibited from making the severity of my sentences the index of my effectiveness,” she said in a statement. “What has become abundantly clear through this process is while I currently do have discretion to pursue death sentences, I have determined that doing so is not in the best interests of this community, or in the best interest of justice.”

Governors of several states, including Washington, Oregon and Colorado, have also imposed moratoriums on the death penalty while they are in office.

Controversial drugs are in short supply and pharmaceutical companies are taking a stand

The Republican governor of Arkansas, Asa Hutchinson, defended his state’s string of planned executions this month by saying it needed to carry them out before one of its drugs used in lethal injections expired.

“It is uncertain as to whether another drug can be obtained,” Hutchinson said in a statement.

The drug in question is midazolam, a sedative that’s part of a three-drug cocktail the state uses in lethal injections. The drug has been tied to several faulty executions, including those in Oklahoma; Arkansas’ supply expires at the end of April.

Another drug the state uses in executions is vecuronium bromide, a muscle relaxer. McKesson Corp., a medical supplier that sold the drug to Arkansas, took the state to court over it. The company says Arkansas purchased the drug, which McKesson says is intended only for medical use, under false pretenses.

The controversy over execution drugs goes beyond Arkansas and extends to the federal government.

In one example, the Texas prison system filed suit this month against the Food and Drug Administration, which seized 1,000 vials of an execution drug whose importation was banned in 2015. The state purchased the drug, sodium thiopental, from India, and the FDA wants it shipped back or destroyed. The Texas Department of Criminal Justice argues that law enforcement agencies are exempt from the ban.

Major court cases loom as states reexamine policies

Outside of Arkansas and Texas, several other court cases over the death penalty are looming.

In Cincinnati, the U.S. 6th Circuit Court of Appeals is scheduled in June to have the full court consider whether Ohio’s use of a three-drug cocktail in lethal injections is unconstitutionally cruel and unusual punishment. Earlier, a three-judge panel in the appeals court had upheld a stay that kept the state from using the procedure in executions.

In California, the Supreme Court is expected to decide this summer on challenges to a voter-approved proposition that reduces the time allowed for appeals of death sentences. The new rule was intended to speed up executions in the state, where there are nearly 750 people on death row. The state is considered a "symbolic" death penalty state because capital punishment is legal but has not been used since 2006.

States are also reconsidering their use of the death penalty.

In Oklahoma, a state commission said this week that a moratorium on the death penalty should be extended until the system for carrying out sentences is changed so that innocent people do not die.

“Ultimately we found that there are many serious systemic flaws in Oklahoma's death penalty process that obviously can and have led to innocent people being convicted and put on death row,” former Oklahoma Gov.

The state had been under scrutiny since a series of botched executions, and it imposed a moratorium in 2015 after the wrong drug was used in one. In a high-profile 2014 execution, inmate Clayton Lockett was struggling for 43 minutes on the gurney after a lethal injection before he finally succumbed.

Jaweed Kaleem is The Times' national race and justice correspondent. Follow him on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.