Texas schools pressed to accommodate influx of young immigrants

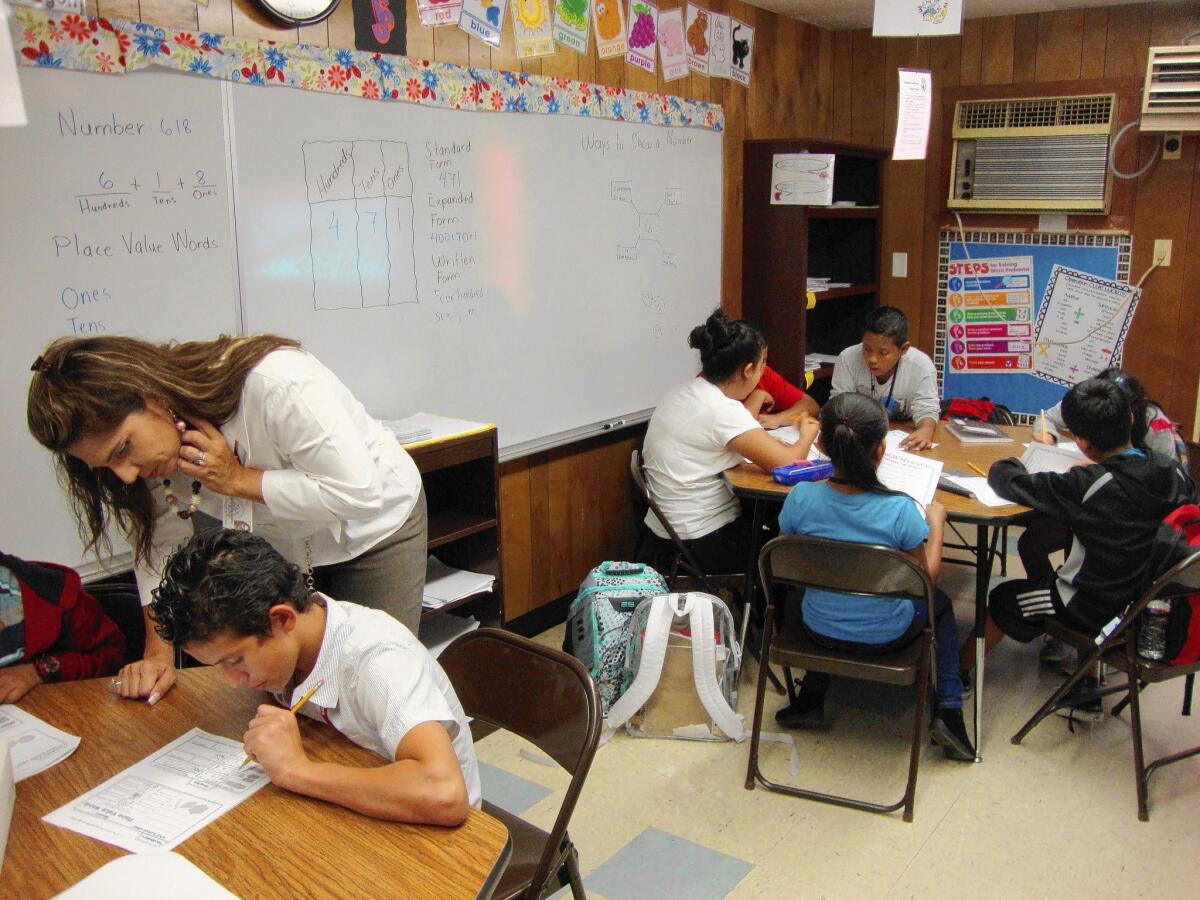

A year ago, the Las Americas Newcomer Middle School serving the low-income Gulfton neighborhood started the semester with 150 immigrant and refugee students. When the new school year began last month, enrollment skyrocketed to 325 students, most of them newly arrived from Central America.

“It’s put a burden on me because I’ve run out of space,” Principal Maria Moreno said of the school’s dozen portable classrooms set up behind another middle school. She hired five new teachers and a social worker, converted a teacher lounge and school police office into classrooms and used surplus funds to buy projectors, laptops and desktop computers.

But she has still had to turn away more than 100 students.

“That’s not going to stop,” Moreno said. “Since I can’t handle them, they’re going next door. But is next door equipped to handle them?”

That’s a question facing educators across the country. School districts from California to Georgia and Maryland have had to add bilingual programs and social services to help new migrants, with Oakland hiring an “unaccompanied minor support services consultant.”

Miami-Dade County Public Schools in Florida, home to one of the country’s largest Honduran communities, has requested federal assistance after enrolling 1,469 Central American students since the end of last school year, including 901 from Honduras.

But nowhere is the impact of the recent surge of immigration felt more strongly than in Texas.

More than 66,000 unaccompanied young immigrants crossed into the U.S. illegally in the past fiscal year, most entering through Texas’ Rio Grande Valley.

Of those, 37,477 had been released to sponsors across the country as of July 31, according to the Office of Refugee Resettlement. California has received 3,909 children, while the largest number — 5,280 — has gone to Texas. Of those, 2,866 have been placed in Houston and the surrounding county.

Texas had long served students who were in the country illegally, and a landmark 1982 Supreme Court case held that the state could not deny them an education. Texas also absorbed 35,000 students after Hurricane Katrina.

The current wave, though smaller, presents special challenges to educators. Many of these students, Moreno said, are fleeing countries in turmoil and need counseling and other social services.

There’s the 12-year-old student at Las Americas sent north by her mother from El Salvador after her cousin was gang-raped. The 11-year-old Salvadoran girl who persuaded a priest to smuggle her north without her mother’s consent. And the 14-year-old Honduran boy whose mother brought him as far as Guadalajara, Mexico, then ran out of money and told him to hop cargo trains the rest of the way.

Most students don’t speak English. Some indigenous children barely speak Spanish, like the Honduran boy who spoke Mayan Quiche and kept asking Moreno in Spanish, “How do you say this in Spanish?”

One Salvadoran father recently brought his 13-year-old daughter to Moreno’s office in tears. He had left for the U.S. when the girl was 4 months old. Now she had made the trek north and was running wild, testing his temper.

“Dad has no clue” how to parent, Moreno recalled. “And the girl is sitting here crying, saying, ‘I don’t know this man.’”

Moreno, who has two sons, ages 11 and 20, tried to offer the father advice.

“I said, ‘Call me when you don’t know what to do,’” she recalled. She said she left the conversation wondering, “How do I coach this parent?”

The Las Americas school, which serves grade 4 through 8, has students from 23 countries who speak 17 languages. Arabic, Nepali and Swahili were more common than Spanish until recently. Houston public schools, which plan to expand the Newcomers program, have already enrolled 1,825 new students from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

Some Texans fear that the state cannot afford to serve the newcomers. But Texas Education Agency officials, who oversee the state’s more than 1,200 school districts and charters, say they already budgeted to cover the extra students and can draw upon a state fund with a $263-million surplus if new costs arise.

Agency officials estimate that it will pay districts $9,473 to educate each bilingual student this academic year. That’s $1,573 more than it paid for the typical student.

If most of the young immigrants placed in Texas enroll in school, the total cost of educating the newcomers could top $50 million.

A conservative Washington-based group puts the cost even higher.

The Federation for American Immigration Reform predicts, based on past studies, that 98% of unaccompanied minors will enroll at a cost 75% higher than the average student. In Texas, the federation predicts, that means about $15,000 per student annually, or about $78 million this year.

Nationwide, the group says that educating unaccompanied minors this year will cost more than $761 million.

Federal officials say that it’s difficult to estimate how many of the young immigrants have enrolled. The U.S. Department of Education has released guidance to schools, but has not tallied costs.

“The financial impact of unaccompanied immigrant children is an incredibly complicated number to calculate in a particular state, district or school, much less nationally. It depends on a range of local factors,” department spokeswoman Dorie Nolt said.

Those factors include the number of English-as-a-second-language students already in a school and the level of community programs and state support. Also key is existing enrollment, Nolt said, adding that some urban districts are underenrolled and may have extra capacity.

“There was this concern at first that there was going to be this flood of kids,” Nolt said. “Some urban districts have seen a lot, but the vast majority have not.”

But Republican Rep. Lamar Smith of San Antonio and other Texas conservatives complain that the migrants will place new demands on already overcrowded schools.

“Regrettably, American taxpayers will be asked to foot the bill for the burden on these school districts,” Smith said.

In the Houston area, Liberty and Galveston counties, along with the cities of Magnolia and League City, recently passed resolutions condemning federal efforts to house migrant children in temporary shelters or directing officials not to cooperate with federal authorities to maintain the facilities. One resolution branded a shelter a health risk.

In nearby Conroe, residents have been pressing federal officials to close a shelter, concerned that 117 unaccompanied minors have already been placed with local sponsors.

“We know they’re here, but Conroe and the other school districts won’t say a word about how many are enrolled, how much is it costing to educate them, to hire language teachers to teach them in their language,” said Michelle Prescott, president of Montgomery County Citizens Against Illegal Immigration.

Prescott, 46, has a son in high school and echoed the concerns of officials in other states that, without documentation, it may be difficult to screen out immigrants who are too old or unvaccinated. She said that leaves parents “not knowing who your child is sitting next to in history class.”

Moreno has spoken to conservative community groups and tried to allay such concerns, noting she screens birth certificates and proof of immunization.

“What’s better than having an educated child who can get a job and pay taxes?” she said. “You want them to be educated and fend for themselves.”

As Moreno walked among classrooms Monday, she stopped to talk to the 14-year-old Honduran boy who rode the trains north and has transformed himself, in a few short weeks, from class clown to dedicated student, she said.

In a math class of 30 students, a girl with curly brown hair and dangling gold earrings gave Moreno a shy wave. It was the 13-year-old Salvadoran who had been struggling with her father.

Moreno bent low, whispering to the girl that she would catch up with her later. The girl’s father had not telephoned the principal for help this weekend. Moreno took that as a sign of progress.

molly.hennessy-fiske@latimes.com

Twitter: @mollyhf

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.