Opioids prescribed by doctors led to 92,000 overdoses in ERs in one year

Prescription drug overdoses, a dangerous side effect of the nation’s embrace of narcotic painkillers, are a “substantial” burden on hospitals and the economy, according to a new study of emergency room visits.

Overdoses involving prescription painkillers have become a leading cause of injury deaths in the U.S. and a closely watched barometer of an evolving healthcare crisis. Little was known, however, about the nature of overdoses treated in the nation’s emergency rooms.

A new analysis of 2010 data from hospitals nationwide found that prescription painkillers, known as opioids, were involved in 68% of opioid-related overdoses treated in emergency rooms. Hospital care for those overdose victims cost an estimated $1.4 billion.

The estimated 92,200 hospital visits were more than five times the number of deaths involving opioid painkillers that year.

“What this study shows us is opioid overdose deaths are just the tip of an iceberg,” said Andrew Kolodny, an addiction doctor who helped found Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing.

In a report published online Monday in JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers from Stanford University, the University of Pennsylvania, Brown University and Rush Medical College analyzed data from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample and adjusted the raw figures to generate national estimates.

Researchers found that fewer than 2% of the overdoses treated in emergency rooms were fatal. But in more than half the cases, victims had to be admitted to the hospital.

“Further efforts to stem the prescription opioid overdose epidemic are urgently needed,” the researchers concluded.

U.S. Atty. Gen. Eric H. Holder Jr. made the same point in a speech to the nation’s police chiefs Monday. He unveiled a Justice Department “tool kit” to guide law enforcement agencies responding to drug overdose calls and encouraged police departments to provide officers with naloxone, a fast-acting antidote that can reverse overdoses and prevent death.

“It’s absolutely critical that we equip them to respond appropriately,” Holder said.

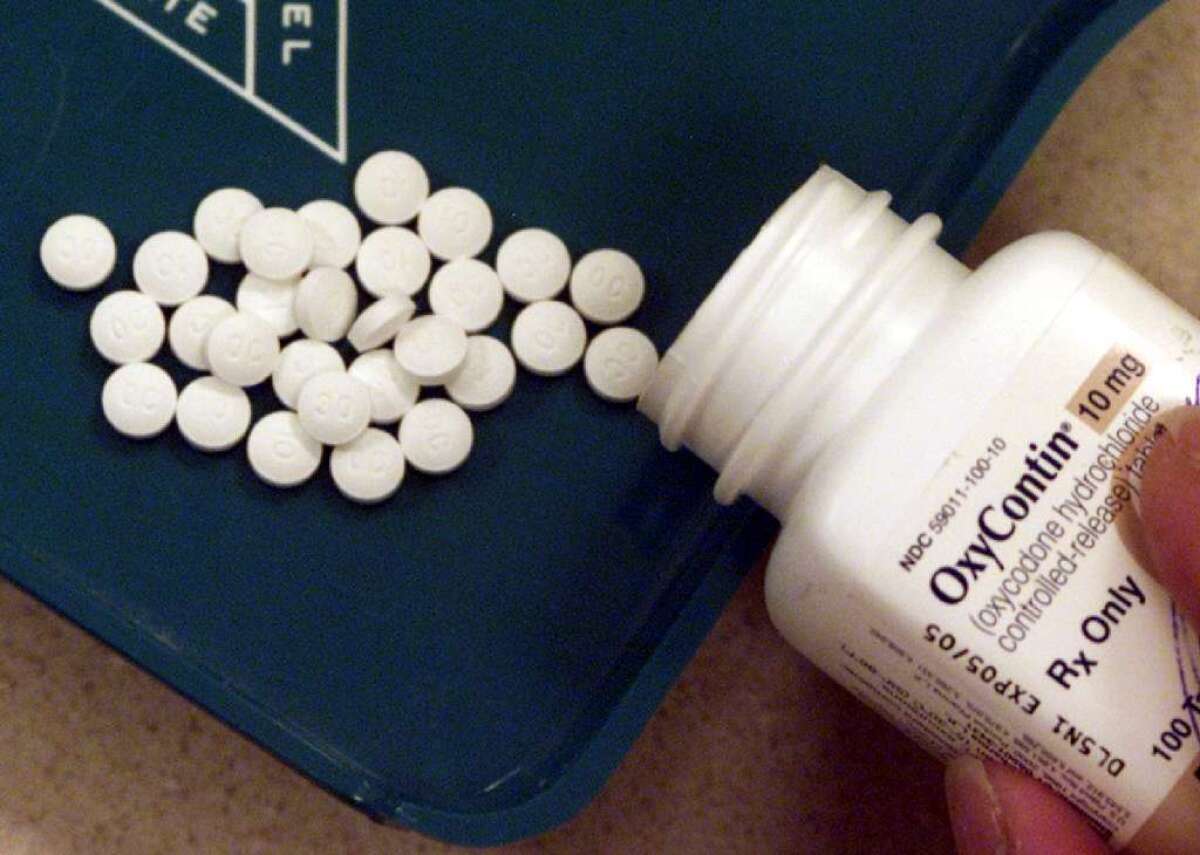

Opioid drugs — including forms of morphine, methadone, oxycodone and hydrocodone, such as OxyContin and Vicodin — are prescribed for patients who need powerful painkillers. But if patients take them for an extended period, they can develop a tolerance and require higher and higher doses of the drugs, making an overdose more likely. Patients who have too much of these drugs in their systems may lose consciousness and stop breathing.

Painkiller deaths quadrupled between 1999 and 2011, mirroring a sharp rise in the number of prescriptions for such drugs. In 2009, overdoses involving painkillers pushed drug fatalities past traffic accidents as a cause of death. And in 2011, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention declared an epidemic.

The crisis had long been blamed on pharmacy robberies, teenage pill poppers and the black market. But a 2012 Los Angeles Times study showed that physicians played an important role in prescription drug overdoses. The Times analysis of 3,733 fatalities found that drugs prescribed by physicians to patients caused or contributed to nearly half the deaths.

In response to the epidemic, almost every state has created a prescription drug monitoring program so physicians can log into a computer to check whether a patient is getting a dangerous narcotic from another physician.

Proposition 46 on the November ballot would require physicians to check California’s prescription drug monitoring program, known as CURES, before prescribing certain drugs. The Medical Board of California is preparing to adopt new guidelines for prescribing opioid painkillers. And Gov. Jerry Brown recently signed into law a bill that allows people to buy the naloxone overdose antidote injector pens and nasal sprays without a prescription.

The new study tallies some of the costs of overdoses. About 41% of the patients who went to a hospital after taking prescription opioids were treated in the emergency room and released; 55% were admitted to the hospital. And 4% were transferred to an acute care hospital. Among those who became hospital inpatients, the average stay was 3.8 days, and their average charges came to $29,497. For patients who were released without being admitted, the average charges were $3,640. Altogether, the cost of treating both groups of patients was nearly $1.4 billion in 2010.

The study found that patients who needed emergency care for an overdose of prescription opioids were most likely to be from the South (40%); to be between the ages of 18 and 54 (66%); and to live in a ZIP Code where the median income was below $67,000 (79%).

People with breathing, heart and mental health problems were at higher risk for drug overdoses, the study showed.

“That suggests that when a clinician writes a prescription for opioid painkillers for someone with one of these conditions, they need to do so with care,” said Michael Yokell, a Stanford University medical student and one of the researchers.

“They need to think about alternatives,” he said. “And if they choose opioids, they need to have a conversation ... about the risk of overdose.”

Emergency room physicians said the findings reflected their experiences.

Dr. Cesar Aristeiguieta, who runs an emergency room in Houston, said physicians prescribed more narcotic painkillers out of a desire to relieve their patients’ suffering and in response to pressure from medical boards and other health policymakers.

“Now we are seeing people can obtain narcotics easier than street drugs — and for free or low cost with insurance,” Aristeiguieta said. “It’s no wonder we’re in the situation we’re in.”

Twitter: @lisagirion

Twitter: @LATkarenkaplan

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.