Beverly Hills quakes at intersection of two faults

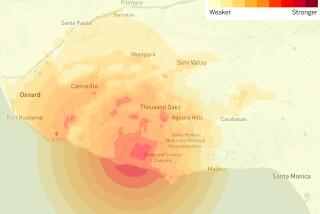

The two earthquakes that struck Beverly Hills and shook a good portion of Los Angeles this week occurred at the intersection of two dangerous faults.

Although both faults are capable of producing a 7.0 temblor, experts said the quakes are probably not foreshocks to a larger quake.

U.S. Geological Survey geophysicist Doug Given said the quakes occurred near the junction of the Santa Monica fault, which runs underneath Pacific Palisades, Santa Monica, Westwood and Beverly Hills, and the Newport-Inglewood fault, which produced the deadly 1933 Long Beach quake.

The earthquakes that hit this week — a 3.2 on Monday, centered near Doheny Drive and Wilshire Boulevard — and a 3.4 after midnight Friday, centered near Wilshire Boulevard and Beverly Drive — were shallow.

“As a result, they were strongly felt,” Given said.

Both quakes were felt over a wide area because they run through heavily populated sections of Los Angeles County. There were no reports of major damage.

Both faults are quite long, meaning they are capable of producing a destructive quake. Because they run underneath the Westside and western Los Angeles County — heavily populated areas — there is “significant population at risk because of them,” Given said.

The Newport-Inglewood fault, beginning just off the Orange County coast and extending 50 miles northwest through Long Beach, Inglewood and into Beverly Hills, has been the subject of dire quake scenarios because it runs directly under some of the most densely populated areas of Southern California.

The Long Beach quake was a 6.3 temblor centered off the Orange County coast that killed 115 people, mainly in Long Beach and Compton. That was the second-largest number of fatalities in a California temblor in recorded history. Damage to school buildings caused by that quake led to major steps toward earthquake-resistant construction in the state.

A state study found that a quake along the Newport-Inglewood fault could block the 101 Freeway at the Hollywood and Sunset boulevard over-crossings, reduce the capacity of Los Angeles International Airport to 30% of normal for two days, remove for an indefinite period 34% of hospital beds in Los Angeles and Orange counties, shut down five power plants for three days and contaminate water supplies.

A scenario simulating a 6.6 earthquake on the Santa Monica fault estimated that 54,000 buildings could be damaged, including 85 beyond repair. Under the scenario, a quake on the fault could kill as many as 30 people and force the hospitalization of more than 200 people.

In 2009, a 4.7 earthquake centered near Inglewood shattered some windows and caused ceiling tiles to fall in a movie theater.

The Beverly Hills temblors came the same week as a magnitude 7.6 earthquake in Costa Rica, but officials said they see no connection.

And although it might seem like Southern California is feeling more quakes these days — including a swarm of temblors in Imperial County and several quakes in Yorba Linda — officials said it’s really not unusual.

“We have several of these things every week in California, but usually they’re out somewhere where they don’t get this kind of attention,” Given said. He said that the Beverly Hills quake attracted significant attention because it hit underneath a heavily populated area.

Given said this was a reminder that residents need to know “they live in earthquake-prone territory,” and be prepared. “If you sustained damage in this quake, if things fell off your shelves, you’re really not prepared.”

Given said it’s not particularly surprising that two small quakes occurred so close together in geography and in time. “The stress of one may have transferred over and caused a second quake, but that’s not unusual,” he said.

That type of activity is frequent in the region “so this is just standard background seismicity,” Given said.

Statistically, there is a 5% chance that a quake could be a foreshock of a larger, future quake. But there’s no way to predict if any particular small quake could be the precursor to the Big One.

He likened the situation to playing the stacking game Jenga — removing a wooden block is like an earthquake. The Jenga tower could still remain stable after one block is removed. But removing a different block later in the game could cause the collapse of the tower.

And while everyone wants to know when the Big One will occur, the problem is that there is no way to predict it. Chances are the Big One could occur with no warning.

Tips on preparing for quakes, such as how to bolt down bookshelves, televisions and heavy appliances, can be found at https://www.earthquakecountry.info.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.