Rodney King dies at 47; victim of brutal beating became reluctant symbol of race relations

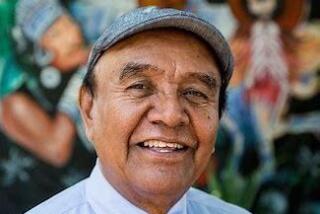

In his Rialto home, Rodney King looks at a photograph of himself from May 1, 1992, the third day of the Los Angeles riots.

Rodney King never set out to be a James Meredith or Rosa Parks.

He was a drunk, unemployed construction worker on parole when he careened into the city’s consciousness in a white Hyundai early one Sunday morning in 1991.

While he was enduring the videotaped blows that would reverberate around the world, he wanted to escape to a nearby park where his father used to take him. He simply wanted to survive.

PHOTOS: Rodney King | 1965- 2012

He did survive, but the brutal beating transformed the troubled man into an icon of the civil rights movement. His very name became a symbol of police abuse and racial tensions, of one of the worst urban riots in American history.

More tangibly, the tape of his beating and the upheaval that followed in 1992 brought about the resignation of the long-reigning Los Angeles police chief, Daryl Gates, and opened the door to widespread police reform in the city and beyond.

But King struggled with the expectations freighted upon him, with addictions, legal problems and financial woes, with the name that transcended the man himself and the ragged reality he lived.

Early Sunday morning, at age 47, King was found dead at the bottom of his swimming pool in Rialto. Authorities say there was no evidence of foul play and are investigating his death as an accidental drowning.

King’s fiancee, Cynthia Kelley, discovered him around 5 in the morning, authorities said. She told investigators that she had been talking to him intermittently through a sliding glass door. At some point she heard a splash, and ran out to find King submerged at the deep end.

Kelley said she could not swim well, so she called 911. When police pulled King out of the water, King showed no signs of life.

From the beginning, King had faltered in his role as a symbol and was tormented by his failings. His stuttering plea for everyone to “get along” during the riots was praised for its earnest intent, yet ridiculed as feckless and naive in relation to such searing, deep-seated anger.

“I never went to school to be ‘Rodney King,’” he told The Times two months ago on the 20th anniversary of the riots.

He didn’t even use that name much; his family called him by his middle name, Glen.

But whatever the transgressions of his life, he caused, however inadvertently, profound change.

FULL COVERAGE: L.A. riots, 20 years later

“Rodney King has a unique spot in both the history of Los Angeles and the LAPD,” Police Chief Charlie Beck said in a statement. “What happened on that cool March night over two decades ago forever changed me and the organization I love. His legacy should not be the struggles and troubles of his personal life but the immensely positive change his existence wrought on this city and its Police Department.”

The Rev. Jesse Jackson said King’s life exposed the nation to racial profiling and police brutality.

“We thank God for the use of Rodney King’s life to lift us to a higher degree of consciousness. Let the burden upon the living be to continue the struggle so that the days of racial injustice will end. Let us answer Rodney’s pressing question: Yes, we all can get along.”

King’s family moved from Sacramento to the foothills of Altadena when he was 2. His parents cleaned offices for a living. His father, Ronald, was a hard-fisted drinker who took his anger out on his son. The boy began drinking in junior high school and often got into trouble with authorities.

I sometimes feel like I’m caught in a vise. Some people feel like I’m some kind of hero. Others hate me. They say I deserved it...

— Rodney King

In 1989, King was accused of attacking the owner of a market in Monterey Park with a tire iron. He pleaded guilty to robbery and received a two-year sentence.

He had just been released when the California Highway Patrol clocked him going west on the 210 Freeway on March 3, 1991, at speeds over 100 mph. It was just after midnight. He saw the flashing lights in his mirror and raced to get away. He had been drinking with friends and knew he’d be back in custody for violating his parole if he was caught. Los Angeles officers quickly joined the pursuit. He stopped eight miles later on a darkened stretch of Foothill Boulevard.

His two friends obeyed orders and got out of the car without incident. King delayed, then got out and acted erratically. He did a little dance, waved to a helicopter whirring overhead and blew a kiss. The cops later said they thought he was on PCP, though he was not.

What happened next was debated and analyzed in granular detail in courts, investigative panels and living rooms for years to come. LAPD officers swarmed King, shot him with Tasers and rained some 50 blows upon him with batons and boots.

PHOTOS: Notable deaths of 2012

A resident named George Holliday caught the beating on videotape, which showed King facedown as he was struck repeatedly by three officers as others stood by watching. Holliday gave the 81-second tape to KTLA, then CNN replayed it the next day, causing a national uproar. The officers involved wrote reports suggesting that the video did not depict the entire confrontation, saying that King rushed at them, swinging and kicking.

The four — Laurence M. Powell, Theodore J. Briseno, Timothy E. Wind and Sgt. Stacey C. Koon — were indicted for the beating on March 15 by a grand jury.

An independent investigative panel led by Warren Christopher simultaneously looked into the issue of brutality by the Los Angeles police. In July, the Christopher Commission released a blistering report, saying “too many patrol officers view citizens with resentment and hostility” and that the problem of “excessive force” was a problem of leadership from the top down. It pushed for sweeping changes, overhaul of the department’s disciplinary system and a shift toward community policing. More pointedly, it called for the combative and militaristic chief to step down.

Gates refused, calling the beating an aberration. Tensions rose throughout the city as the officers’ trial approached in Simi Valley. When all four were acquitted on Wednesday, April 29, 1992, by a jury with no black people on it, the response in the streets was immediate.

A crowd of black men gathered at Florence and Normandie avenues. Police arrived to disperse them, but they were outnumbered and backed off. Gang members pulled a gravel truck driver named Reginald Denny from his cab and viciously assaulted him for 20 minutes before bystanders rescued him as news choppers filmed from above. Smaller groups formed downtown.

By the end of the night, rioters touched off more than 150 fires, stormed police headquarters and ransacked numerous downtown buildings as sporadic gunfire rang through the streets. Mayor Tom Bradley ordered a curfew, and Gov. Pete Wilson called in the National Guard.

Gates was attending a Brentwood fundraiser to defeat a police-reform ballot measure when the rioting started. Several hours passed before he returned to take charge, and by then his officers were in retreat.

The insurrection and looting spread throughout the city over the next few days. Whole blocks of South Los Angeles burned to the ground. Stores were gutted. Military convoys rumbled up and down the smoky streets.

King made his famous plea before the television cameras on Friday, looking like a terrified child groping for what to say. “Can we all get along? Can we … can we … get along? Can we stop making it horrible for the older people and the kids. I mean, we’ve got enough smog in Los Angeles, let alone to deal with setting these fires and things. It’s not right. It’s not right. It’s not going to change anything.”

With the help of 5,700 National Guard troops, federal agents and Marines, police put the riot down after three days. At least 54 people were dead, and property damage amounted to $1 billion.

The next year, the four officers were tried in federal court for violating King’s civil rights. Koon and Powell were convicted and did prison time. Gates stepped down in June. Under heavy pressure from the U.S. Justice Department, the police reforms recommended by the Christopher Commission gradually took effect.

King sued the city and won $3.8 million in damages. He told The Times that after his legal fees, he had $1.6 million or so, with which he bought a house for his mother and one for him. He started a hip-hop label that didn’t go anywhere.

He could never find stability in his life. He entered rehab in 1993 after crashing into a wall while drunk. Two years later, he did 90 days in jail after being charged with a hit-and-run for knocking his wife down with his car. He got hooked on PCP for a spell, was shot by pellets riding his bike and had so many encounters with police that in interviews he couldn’t recall them all.

“There was the time my car went off the road and came to a stop on a tree,” he told The Times in April. “PCP ain’t no joke.”

His money dwindling, he bought a fixer-upper in Rialto and struggled to make the mortgage payments. He put a tarp along the back fence to keep people from trying to catch a glimpse of an icon. He earned small paydays doing celebrity boxing matches or pouring concrete at construction sites. But even those odd jobs were hard to get.

He recounted how one employer laughed and said, “Get out of here — too high-profile.”

In 2008, he briefly re-entered the public light when he signed to appear in the TV show “Celebrity Rehab with Dr. Drew.” He then faded away again.

Then this year, the 20th anniversary of the riots, reporters were calling and knocking at his door for interviews, and his book, “The Riot Within,” was published.

He seemed a man still deeply haunted by the past and the expectations of him. He said he suffered nightmares and flashbacks from the beating. He smoked marijuana and drank. He was always trying to calm his raw nerves, swimming in his pool, fishing in a nearby lake with worms he dug from his yard. The water had always been a refuge for him.

“I sometimes feel like I’m caught in a vise,” he said. “Some people feel like I’m some kind of hero. Others hate me. They say I deserved it. Other people, I can hear them mocking me for when I called for an end to the destruction, like I’m a fool for believing in peace.”

He was more contemplative than he had been before. And the man who just wanted to escape to that park his father took him to was beginning to accept his broader legacy.

“Yes, I would go through that night, yes I would. I said once that I wouldn’t, but that’s not true. It changed things. It made the world a better place.”

Civil rights attorney Connie Rice saw King a few weeks ago at an event.

“I’ve never seen him look less broken. He looked happy, and it looked for the first time like he had really kicked his addiction. I know that police love to talk about the fact that he was a criminal. But he was not a criminal. He was a broken and sick man, but did his best not to hurt people. He had a real streak of decency.

“He could have poured gasoline on the fire. At a time when he could have said something destructive … he said ‘Can we all get along?’ When you think about it, there aren’t a whole lot of guys I know that would have done that.”

Times staff writers Kurt Streeter, Andrew Blankstein, Kate Mather and Matt Stevens contributed to this story.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.