Cambodians Divided Over the Past

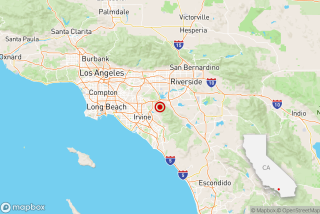

Cambodian Americans gathered at Wat Khmer Temple near downtown Los Angeles on Sunday to celebrate the New Year, kneeling in prayer before a Buddha statue, dancing to a traditional live band and serving fish soup and noodles to the orange-clad monks.

On the same day in Long Beach, survivors of the killing fields held a vigil at a local park to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the start of the brutal communist Khmer Rouge regime that took the lives of more than 1 million Cambodians.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. April 20, 2005 For The Record

Los Angeles Times Wednesday April 20, 2005 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 0 inches; 27 words Type of Material: Correction

Temple slaying -- An article in Tuesday’s California section about a slaying at a Cambodian temple referred to the incident as a shooting. The victim was stabbed.

But just as the New Year’s festival was coming to a close, a fight erupted outside the Los Angeles temple among a group of young Cambodian Americans. Elders, along with security guards, tried to break it up.

But when the altercation ended about 9 p.m., police said, 21-year-old Harry Yang was mortally wounded, stabbed multiple times.

“It looked like wartime,” said Phan Eng, 31, who said he heard screams during Sunday’s melee. “This celebration time is supposed to be happy. It is not supposed to be like that.”

On Monday, the monks sat cross-legged in front of the Buddha statue and prayed for Yang and his family.

Steps away, Los Angeles Police Department detectives investigated the slaying. Officials said they were trying to determine a motive but believe local Asian gangs may have been involved. Police said a suspect was seen running from the temple, but no arrests had been made as of late Monday.

“There was a party and they were just celebrating and dancing, and someone lost their temper,” said Los Angeles Police Det. Alan Solomon. “Over what, we don’t know.”

For Southern California’s Cambodian community, the shooting punctuated an emotional few weeks in which its members have publicly debated how to both commemorate the solemn anniversary and celebrate the New Year.

The conflict divided the older generation, who believe April 17 should be a day of remembrance for the dead of the killing fields, and the younger generation, who did not experience the horrors of that time.

Roughly 28,000 people of Cambodian descent live in Los Angeles County, according to the U.S. Census, with the largest community in Long Beach. For the last four years, the community has held a New Year’s celebration at El Dorado Park in Long Beach.

This year, Long Beach City Councilwoman Laura Richardson helped sponsor and plan an inaugural New Year’s parade to be held the day after the festivities in the park. She and others proposed that the park festival be held April 16 and that the parade take place April 17.

But a group of elder Cambodian immigrants and refugees immediately opposed the plan.

To them, April 17 holds sacred meaning. It was the date that Pol Pot stormed into Phnom Penh and began his four-year reign. Between 1975 and 1979, Pol Pot aimed to wipe out the past in Cambodia and start a utopia. During that time, Khmer Rouge soldiers executed, starved or tortured Cambodians throughout the country. The reign of terror ended with Vietnam’s invasion in 1979.

Critics of the April 17 parade formed an organization called the Killing Field Memorial Task Force to protest holding the parade on the 17th. The task force also set a goal to build a shrine and museum about the killing fields to teach young Cambodian Americans the history and the legacy of that deadly time in Cambodian history.

Paline Soth, 53, who lost his father, two brothers and grandparents, is part of the task force. Soth said the younger generation did not understand the suffering and sorrow that he and others still feel over losing so many family members.

Soth shaved his head in protest and went to the council to beg officials to change the date. “We view April 17 as a day of mourning instead of celebration,” he said. “April 17 is in the anthem of the Khmer Rouge.... It’s very symbolic. It’s very painful.”

The younger Cambodian Americans knew about the killing fields. They knew about April 17. But they also knew that there were New Year’s celebrations elsewhere that same day, and they believed that the community should move forward, said Lina Heng, 21, the president of the Cambodian Student Society at Cal State Long Beach. The committee planning the Cambodian New Year parade also did not want to change the date because the city had not yet guaranteed a new date.

“We recognized the date as a sensitive date,” Heng said. “We understood, but for us, it’s all about moving on.”

With both sides holding their ground, tensions escalated. Heng, who was born in Long Beach, said people called her and fellow classmates communists and students of the Khmer Rouge. Richardson said there were threats made and car windows smashed.

Finally, the community reached a compromise. A killing fields memorial service would be held at MacArthur Park on the 17th, and the parade along Anaheim Street would be moved to April 24. At tonight’s meeting, Richardson said, the council also plans to sign a proclamation setting April 17 as a day of mourning.

“We have a single Cambodian population in the city, and it’s important we recognize the historical background of that community,” Richardson said in a phone interview Monday. But she added that the disagreement should have never escalated.

Heng, the Cal State Long Beach student, said she was pleased by the compromise but saddened by the division.

“It kind of comes from what happened 30 years ago,” she said. “It was a wound that wasn’t healed yet. It was a wound that was opened again.”

At the Los Angeles temple, congregants were dealing with new wounds.

Solomon said Asian gangs were a problem in the area surrounding the temple, on Beverly Boulevard near Union Avenue. Some of the gangs are made up predominantly of Cambodian youths, he said.

Sok Mom, the president of Wat Khmer Temple, said he hoped to gather youths from the community to discuss the violence. Mom also hopes to have the police monitor future celebrations at the temple.

On Monday morning, he joined the monks to chant in the sanctuary.

“I feel very sad,” said Mom, 58, who is an interpreter. “We will try to solve this problem to make our community better. We don’t want something like this to happen.... We are all Cambodian.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.