Scoutmaster’s slaying, sexual abuse claims roil New Jersey town

STILLWATER, N.J. — Dennis J. Pegg was happy to pay local boys a few bucks to mow the lawn at his house, which sat atop a hill overlooking the elementary school. He was eager to guide Boy Scouts as they mastered the skills of the great outdoors, and to assist hikers trekking the nearby Appalachian Trail.

Pegg appeared to have no enemies in his close-knit, lakeside town of leafy glens and rolling hills — until last June, when his throat was slit and he was repeatedly stabbed in a killing that has raised questions about whether Pegg exploited his position in the Scouts for years to molest young boys.

“This is a really, really ugly story. The blood of this man is on the hands of many people here,” said Carol Fredericks, whose brother-in-law, Clark Fredericks, 46, confessed to the slaying. Pegg, who was 68, had been a local scoutmaster in the 1970s, when, Carol Fredericks said, Pegg sexually abused Clark and others.

Others have since echoed his claims, clouding the image of a man whose online obituary drew sentimental tributes from scores of people who knew Pegg as a bird-watcher; as a “trail angel” who gave food and water to hikers; as a former corrections officer with the Sussex County Sheriff’s Office; as an Army veteran and firearms expert; and as a mentor to local youth.

The case is playing out as the Boy Scouts of America contends with a national scandal arising from its handling of past sexual abuse allegations. Hundreds of confidential files released in recent weeks show that leaders molested the boys they were supposed to be mentoring, and often were never held to account. The files have stirred uncomfortable memories and anger among men around the country who say they have been abused in the Scouts.

Pegg was not in the files, either because he was never written up by the Scouts or because the records were destroyed.

A photograph on the Facebook page of the Stillwater Historical Society, where Pegg was an active member, shows a cheerful, burly man leaning on a walking stick, smiling warmly and waving at the camera.

“I’d have put my life in his hands. I trusted him that much,” said one of his fiercest defenders, attorney Ernest Hemschot III, who had dinner with Pegg two nights before he was killed and who now represents his estate. Pegg, who never married or had children, divided his belongings among a circle of close friends and two nephews.

Hemschot said he and others were stunned by the accusations against Pegg, whose large, granite headstone reads in part, “vir spectabilis,” or “notable man.” “If it did happen, my heart goes out to the victims. But I just find it hard to believe,” Hemschot said. “He was the go-to guy, the one anybody who had a problem or difficulty went to for help.”

That’s not the way Fredericks saw Pegg, and when he went to see him on June 12, friendship was the last thing on his mind.

That night, Fredericks, who lived with his mother a few minutes’ drive from Pegg, got his friend Robert Reynolds to go with him to Pegg’s house. They got in through the unlocked front door and, according to an arrest report, Fredericks immediately began stabbing Pegg. The pair then fled, leaving Pegg with his throat slashed and his torso punctured. Blood soaked the carpet and a leather recliner in the front room. Nothing was stolen — not the DVD player, jewelry box, shotguns, rifles or ammunition.

Fredericks’ mother became alarmed after her son came home about 2 a.m., his hands and clothes bloodied. She alerted the counselor her son had been seeing, saying she feared Fredericks “may have hurt or killed someone,” according to a police affidavit. Hours later, as he was arrested, Fredericks told police “in effect that the victim got what was coming to him, and that he has been a child molester for years,” the affidavit said.

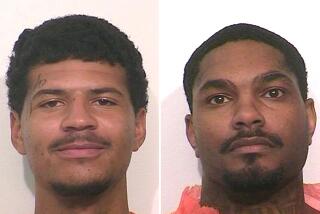

Fredericks was charged with first-degree murder, but that could be downgraded to manslaughter — which carries a prison term of five to 10 years — if investigators are convinced that horrors of past abuse drove Fredericks to spin out of control. Reynolds, who has not alleged abuse by Pegg, is charged with being an accomplice to murder, conspiracy and evidence-tampering.

Both have pleaded not guilty.

Many, including Fredericks’ relatives, are convinced he was driven to act after following coverage of the sexual abuse trial of former Penn State University assistant football coach Jerry Sandusky, which began June 11.

Already, “multiple people” have bolstered Fredericks’ claims, said Sussex County Assistant Prosecutor Gregory Mueller.

Investigators face challenges because the alleged molestations occurred more than 30 years ago, and because of the absence of physical evidence and of law enforcement and Boy Scout records that might have shown decades-old complaints about Pegg.

One person recalled seeing a box containing photographs of child pornography in Pegg’s home, but a search warrant failed to turn it up. “The witness described seeing this box roughly 35 years ago, so it’s not overly surprising we were unable to find it,” Mueller said.

At least one person is believed to have gone to state police in the late 1970s with complaints about Pegg, Mueller added. But the statute of limitations for sexual assault at the time was five years, and state police had a policy of destroying closed-out files.

A spokesman for the Boy Scouts, Deron Smith, said the national office had no files related to Pegg, who was registered with the Boy Scouts from 1973 to 1980 as a scoutmaster in Stillwater and then in Bloomingdale.

That’s the time that a man known in court documents as John Doe 1, who has backed up Fredericks’ allegations, was in the Scouts. John Doe 1’s attorney, Kevin Kelly, says his client was lured to Pegg’s home with promises of money for mowing the lawn. Pegg invited the boy, a sixth-grader at the time, into his home, plied him with beer, showed him pornography and had sex with him, Kelly said.

Afterward, Pegg would have the boy shower and wipe him down with witch hazel to erase evidence, Kelly said. When the boy tried to break off contact, Pegg followed him after school, to the roller rink and elsewhere. Eventually, Kelly said, Pegg gave up and “moved on” to other boys. The man, now 47, gave a similar account to the Star-Ledger of Newark, N.J.

Mueller said prosecutors had interviewed John Doe 1 and that his allegations “are supported and corroborated by other aspects” of the investigation.

Like Fredericks, John Doe 1 still lives in the area. Those who know both men — neither of whom is married or has children — say they were plagued by Pegg’s presence in Stillwater, a rural area 70 miles west of New York City. Both are said to have struggled under the weight of keeping the past secret from relatives and friends.

Kelly’s client lives with his parents and is unemployed. Fredericks, also unemployed, was trying to start his own tire repair business.

The case is the subject of speculation and rumor in Stillwater. Much of the talk takes place at a local market, which serves as the water cooler for residents who stop by for fishing worms, deli sandwiches or just coffee and conversation.

Locals who say they had found Pegg “creepy” because of his focus on boys and young men acknowledged that they would wave hello when they saw him at local events or at the diner, and that they knew him as a Facebook friend.

Pegg seems to have been aware that some harbored suspicions about him, even if they never came right out and said so.

“In a rural community, there’s always somebody looking at you funny, like, ‘Why are you doing this?’” he said in a 2003 story in the Record newspaper about his reputation for helping hikers. “It hurts.”

Times staff writer Jason Felch contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.