Old foundry a diamond in the rough

Off the bustling main street of this erstwhile Gold Rush boomtown, up a lane from the B&Bs and renovated brick storefronts and flocks of tourists, a bulky and aged factory looms like an elephant at a tea party, its windows cracked and its corrugated steel roof long ago overtaken by rust.

For better than a century, the industrial menagerie inside Samuel Knight’s iron foundry stirred and shaped the community.

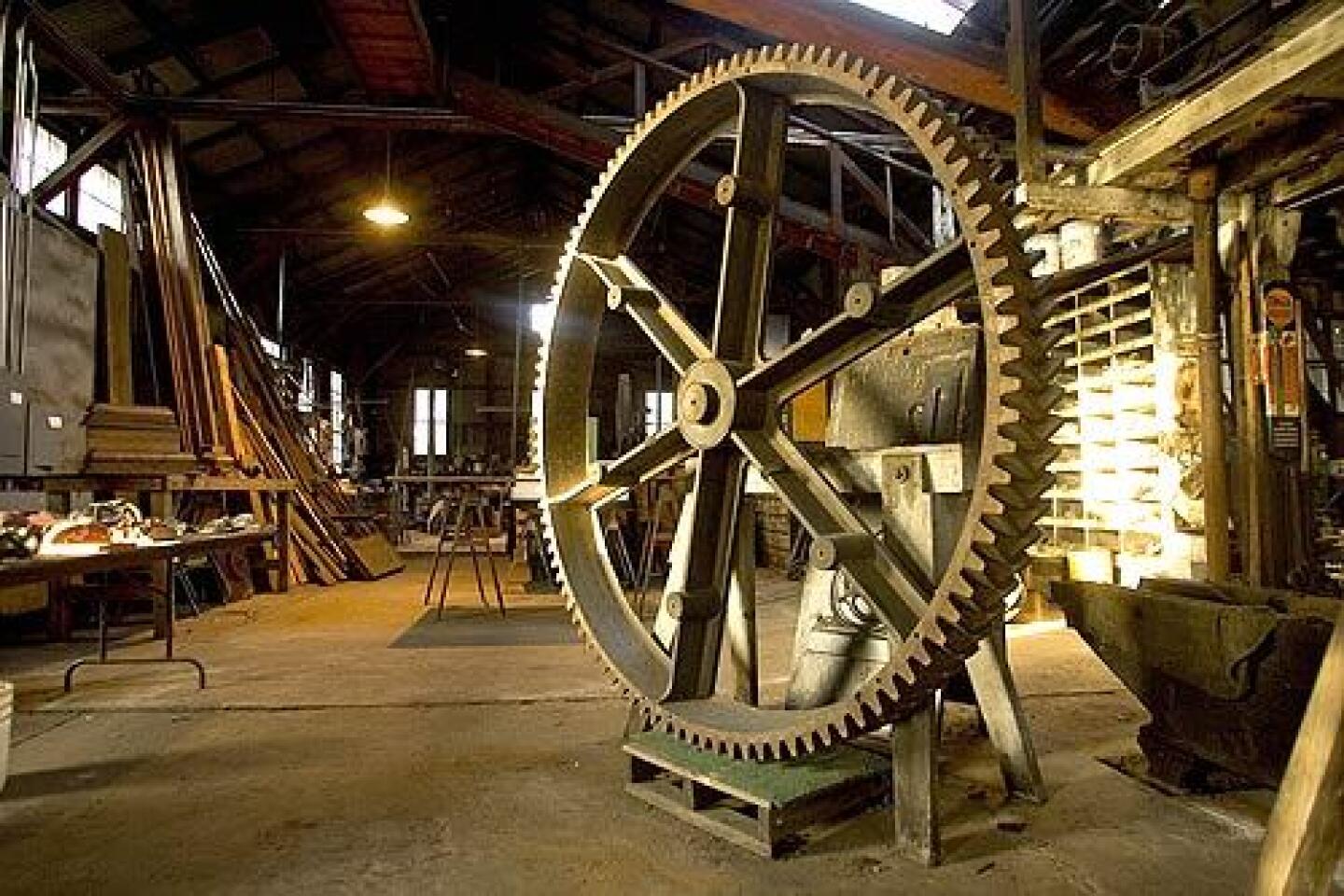

Back in the day, the mammoth blast furnace belched flame and spit out molten metal, its smokestack singing like a pipe organ. Built in 1872, the foundry predated electricity. Water piped from a Mother Lode flume spun old-fashioned turbines, the biggest nearly 4 feet across.

Balanced like a watch, a system of shafts and buffalo-hide drive belts transferred that locomotion throughout the factory, 60 different machines gyrating in a symphony of industry.

Knight Foundry is America’s last water-powered 19th-century ironworks. Closed for the last decade, its machinery silent and its blast furnace moldering, it teetered toward demolition, the sad end for so many industrial heirlooms.

But a few folks, true believers in the faith and labor of pouring iron, are working hard to see Knight Foundry sing again. They yearn for the return of the old-time ironmaster. Russ Johnson might be the last of that line.

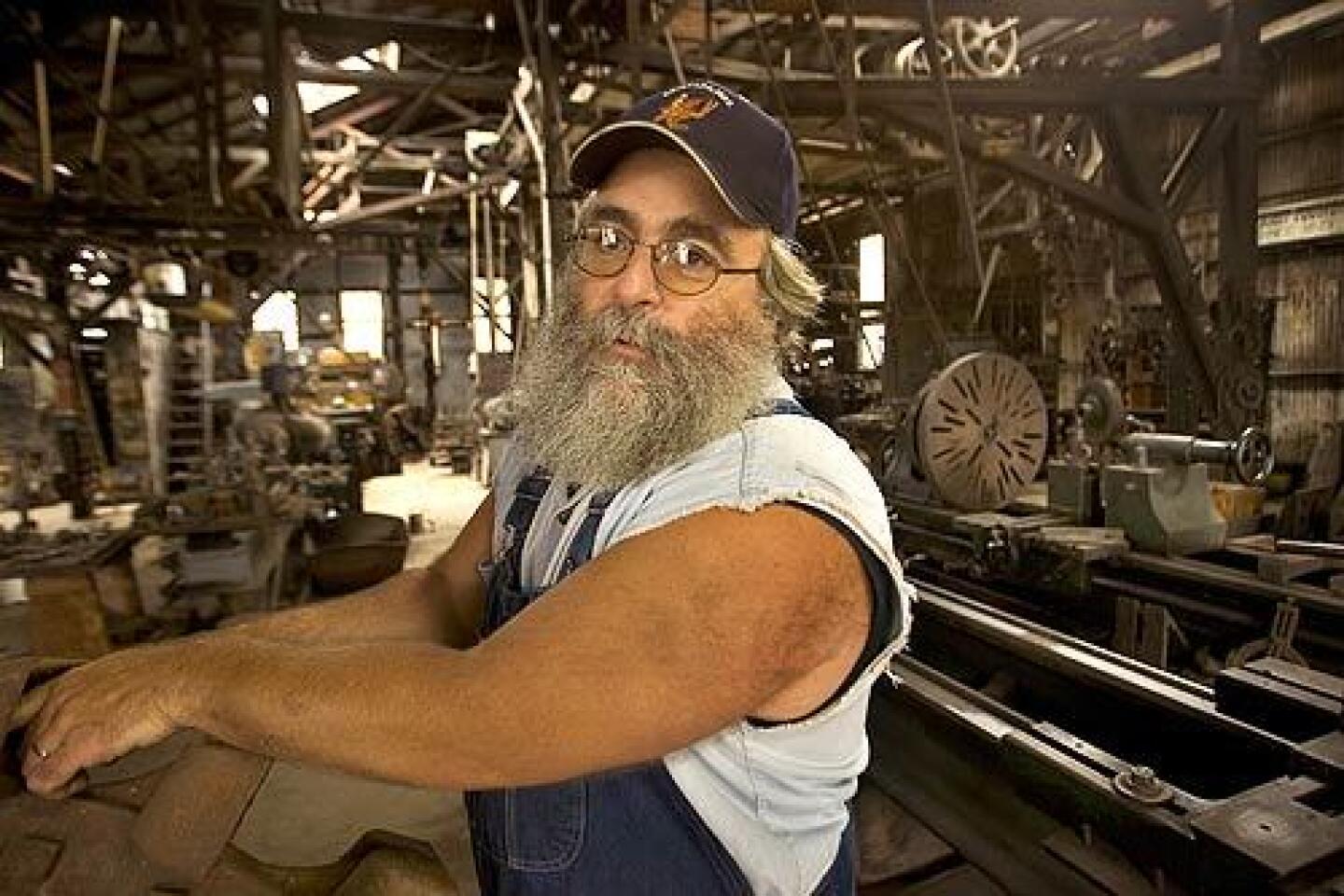

He landed a job at Knight Foundry toward the end of the run, back in 1989. Burly and bearded in his 20s then, Johnson had already dabbled in heavy construction, hanging Sheetrock and hefting concrete. He figured cast iron was a natural next step.

“The work just kept getting heavier,” he says with a laugh.

His arrival came long after Knight Foundry had already become an industrial anachronism.

Small-town foundries were once as pervasive as potbellied stoves on the Sierra’s west slope, transforming iron into things big and small: pickaxes and ore carts, cable car parts and fancy streetlight poles.

As other foundries faded away, an unbroken line of owners and employees at Knight kept finding jobs requiring specialization that the 20th century’s big automated factories couldn’t muster. “Onesies and twosies,” Johnson called them -- reproductions of long-defunct Model A parts and ornamented pillars for the California statehouse. The sort of stuff, he said, that a modern foundry won’t touch “unless it’s an order for 10,000.”

When Johnson slides open the big wood front door of the old foundry, remembrances of his first day still rattle the walls for him.

Men were swearing and sweating. Water-powered machinery hummed gleefully. Johnson loved it.

“I could cuss and get dirty and produce something that at the end of the day I know is going to last a long, long time,” he said.

Cobwebs now hang from dark corners. Dust coats the rafters. Pigeon droppings speckle the floor. But gloves and tools rest waiting, suspended in time as if work stopped yesterday.

Johnson learned his craft from old-school workers, some in their 90s, who had manned the foundry for half a century. Retirees like molder Wendell Boitano and master patternmaker Ernie Malatesta often showed up as if they were still punching a clock.

While shooting the breeze, they passed along tricks of the trade -- the secrets of shaping a three-dimensional pattern out of sugar pine or mahogany, the delicate craft of creating a perfect mold and war stories about iron pours gone sweet or sour.

Such men were Johnson’s link all the way back to Samuel Knight, the Gold Rush and the last days of the Wild West.

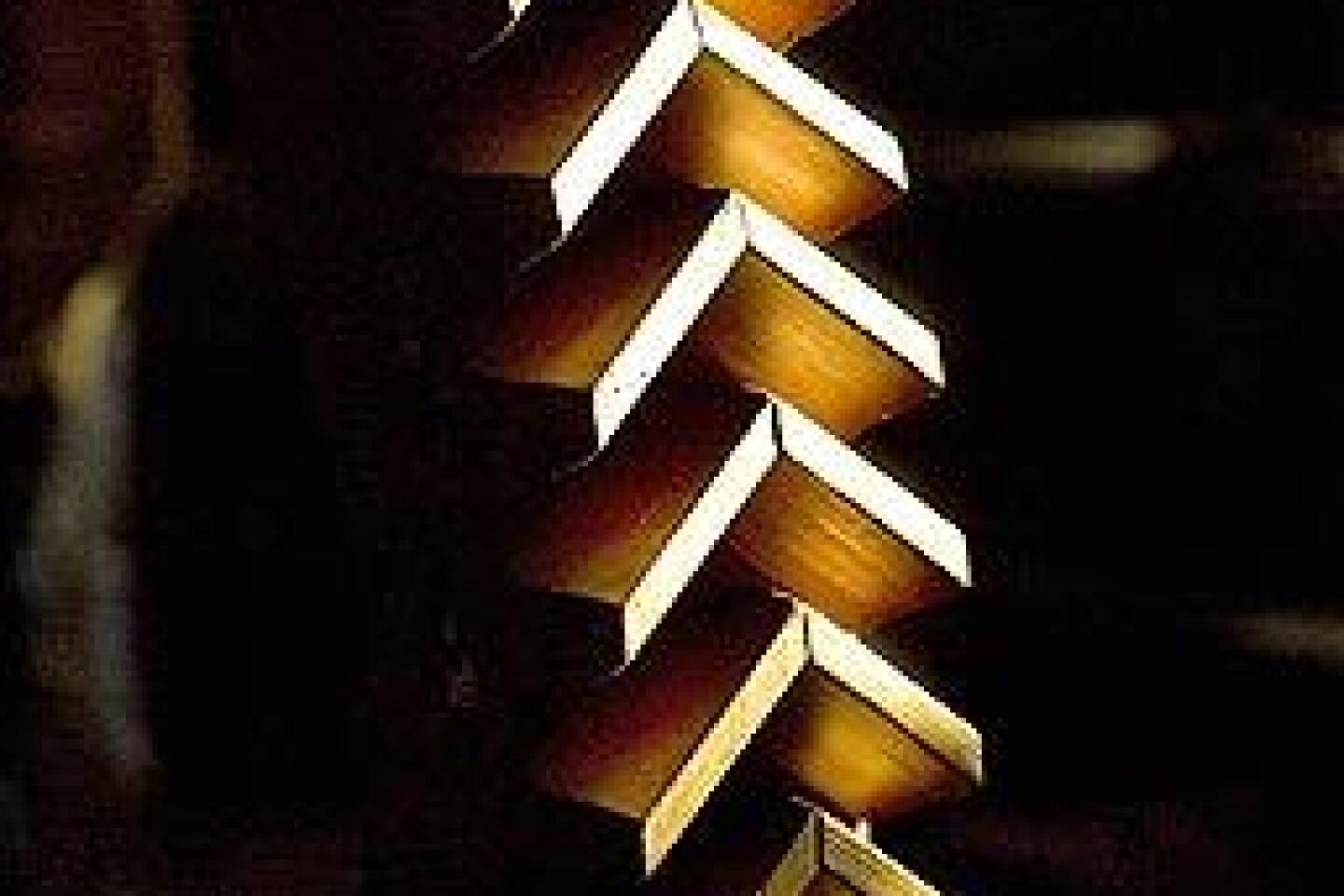

A ship’s carpenter from Maine, Knight came west in 1863 with a head full of ideas. He took the hydraulic principles of the gold fields and applied them to industry, creating a new type of water turbine, the Knight Wheel. Dozens of curved cups at the wheel’s edge tapped the high-pressure force of flowing water to produce enough horsepower for a whole factory.

His foundry manufactured much of the Mother Lode mining equipment. Soon, smaller versions of Knight’s water wheel were powering industry and small appliances.

If he had been good at promoting his work, Knight might have been rich and famous. Instead, competitor Lester Allan Pelton grabbed history’s limelight, perfecting an even better turbine.

Knight stayed at his Sutter Creek factory, running it for four decades.

Before his death in 1913, Knight willed the foundry to his employees, starting a practice of blue-collar inheritance that lasted generations.

That line of succession finally broke when the last of the employee-owners died in 1970. That was when Carl Borgh, an aerospace engineer from Southern California, came in to have some parts cast and ended up buying the factory. He vowed to run the foundry just as it had been run for a century.

Borgh also took on human rehabilitation. He often hired men who were down on their luck, assembling a devoted crew from a motley mix of guys who had trouble with the law, the bottle or both.

That’s when Johnson found his way in the door. He became the cupola tender, heading the pour of white-hot liquid iron.

“This is my office,” Johnson announced on a recent day as he strolled into the blemished section of the factory where the two blast furnaces stand.

Today, Johnson is a father of four. At 46, he sports a Santa Claus beard and is training to operate nuclear surveying equipment for an excavation company. But he still yearns for the pour.

That process never changed at Knight Foundry.

Master craftsmen like Malatesta, who turned to foundry work to avoid the danger of the gold mines, worked the front end of the ritual, carving original patterns out of hardwood. The final shape emerged with the help of lathes, saws and planers, all turned by water power.

Stacked wood frames called flasks formed a box for each mold. Journeymen packed fine white sand around the wood pattern inside. Guarded ingredients went into the mix to solidify the sand -- sea coal, bentonite clay and pitch.

“Secret Squirrel stuff,” Johnson calls the ingredients. “It’s like making sandcastles.”

Workers split the mold into a top and bottom and removed the wood pattern, leaving a hollow impression in the hardened sand to be filled with iron.

They poured every Friday, a day that Johnson jokes was “like working on a chain gang.”

As cupola tender, he kindled the fire and shoveled the furnace full of coke and scrap iron. He loved the “whoop, whoop” of the air compressor and the thundering moan as the blast furnace fired up.

“It’ll rattle the fillings in your teeth,” he said.

Even in winter, the furnace drove building temperatures toward 115 degrees, Johnson said. He’d sweat through his sleeveless shirt, bib overalls and bandanna. He gave up bothering with gloves after one caught on a piece of scrap metal he was tossing into the furnace, almost pulling him into the flames.

As if it were yesterday, Johnson swings a wooden crane into action, its massive chain clanking like a medieval drawbridge to lower a bulky iron bucket used in the pour. The crane’s hardwood girders still bear vestiges of the past -- a tiny foundry-made statue of Babe Ruth and a yellowing 1932 election poster for a long-gone candidate.

As the furnace’s temperature soared past 3,000 degrees, liquid iron poured out like maple syrup. Spills were the enemy. Moisture in the concrete floor would explode, sending shards of hot iron and rock flying. Tiny craters pockmark the concrete, a road map of past mishaps.

When the iron casting cooled, employees cracked open the form and a finished product emerged -- a mortar and pestle, perhaps, or a decorative acorn for a building fresco.

The foundry’s last pour came in 1996. Later that year, the National Trust for Historic Preservation put Knight Foundry on its list of endangered sites.

After Borgh retired, the foundry tried to survive as a museum, offering roped-off tours and weekend ironworker workshops. But insurance costs and a lack of paying production orders eventually shut that down.

Borgh died in 1998, leaving Johnson lower than low. He lost a father figure and most of his hope that the foundry -- put up for sale by Borgh’s estate -- would survive.

Soon, like hot iron filling a mold, good Samaritans stepped into that void.

Andy Fahrenwald, a documentary filmmaker, had come to Sutter Creek to shoot a movie about the foundry. Afterward, he simply stuck around.

For years, Fahrenwald had been fleeing his own family’s blue-collar history in Chicago’s foundries. But the cause of Knight Foundry captured him.

He took on the job of championing the preservation of the foundry and the disappearing skills of men like Russ Johnson, helping to set up the nonprofit Knight Foundry Corp., recruiting volunteers and soliciting donations.

As the clock continued to tick on the foundry sale, another set of benefactors stepped in. Richard and Melissa Lyman, who had made a career of restoring old Victorian homes in Sacramento, put up money to buy the foundry in 2000. They promised to hold it until the nonprofit raised enough to step in.

Over time, the Lymans grew worried that some hidden toxic legacy could saddle them with a huge cleanup bill, even after a sale. Seven years passed with no deal.

The foundry sat -- the machinery silent and the front door padlocked. Johnson came by to keep an eye on things, making weekly visits as he might to a favorite uncle in a rest home.

Finally, this spring the city of Sutter Creek stepped in to buy Knight Foundry. The contract left the nonprofit footing much of the bill in exchange for the keys to run the factory. To complete the $1.3-million sale by a mid-2008 deadline, the property will need a costly environmental cleanup.

Johnson and the nonprofit are busy trying to raise money -- a total of nearly $6 million to cover the purchase, cleanup and restoration of the factory as a working museum. In a town of 2,945, that’s a big price tag. Historical preservationists are watching.

“It needs to be preserved,” said Robert Johnson of the Society for Industrial Archeology. “There’s nothing quite like the Knight Foundry.”

Even now, Russ Johnson won’t allow himself too much optimism. After waiting a decade -- getting another job, watching his children grow up and seeing the factory fall further into neglect -- he’s not banking on anything.

If it works out, Johnson will be the once and future ironmaster of Knight Foundry -- supervising the pour, educating tourists, tutoring apprentices.

He loves the old factory, but it’s the skills he wants to pass on. People say it’s a lost art. Johnson likes to say it isn’t dead or dying or gone. Just sleeping.

eric.bailey@latimes.com

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.