NASA mission to Pluto may have to steer away from moons, debris

Astronomers just keep finding more moons around Pluto. They scoped out the first and largest, Charon, in 1976; the fifth, tiny P5, was spotted just this summer by the Hubble Space Telescope.

Such discoveries are fascinating for planetary scientists, who are working to understand the complex makeup and movements of objects in the Kuiper Belt, the vast field of orbiting icy rocks beyond Neptune that includes dwarf planets like Pluto as well as smaller chunks of stuff.

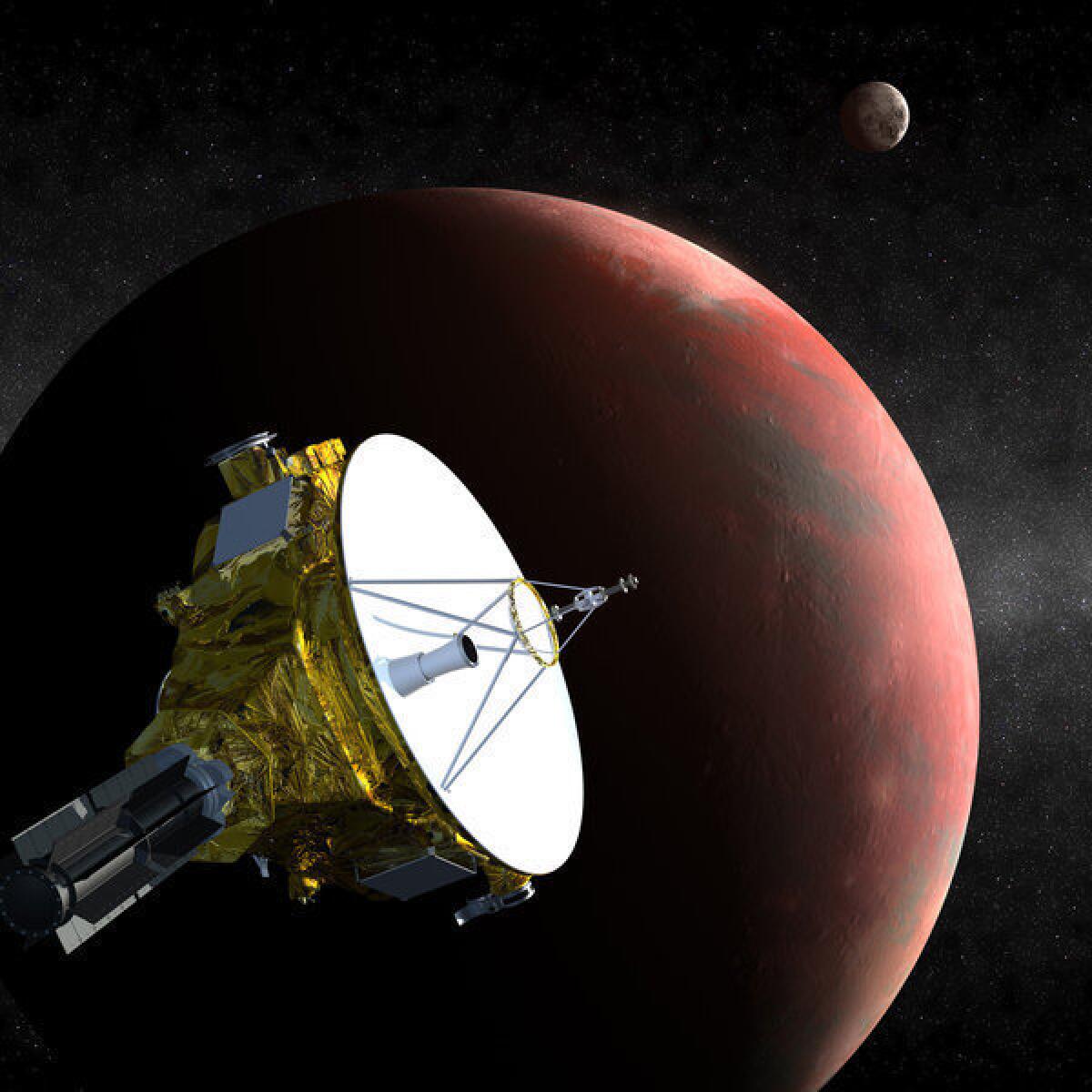

But finding new moons and other stuff floating around in the outer solar system may create headaches for the team operating NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft for the space agency’s mission to Pluto. The piano-sized craft is the fastest ever launched, according to this NASA release. It has been zooming away from Earth for nearly seven years, and is scheduled to make a close approach of Pluto and its moons on July 14, 2015. At that point, it will have traveled 3 billion miles since leaving Earth.

Unfortunately, the more stuff floating around near the speedy spacecraft’s target, the higher the danger that it will sustain crippling damage during its explorations, scientists said at a news conference Tuesday at the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences meeting in Reno.

“Because our spacecraft is traveling so fast — more than 30,000 miles per hour — a collision with a single pebble, or even a millimeter-sized grain, could cripple or destroy New Horizons,” said Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory scientist Hal Weaver, a New Horizons team member, in a statement.

“We need to steer clear of any debris zones around Pluto,” he added.

To avoid a threatening collision, the team has to consider steering their ship on a “bailout trajectory” that would take it farther away from Pluto than scientists had originally hoped, said Southwest Research Institute planetary scientist Leslie Young, who is also a New Horizons scientist. She said that the team would still be able to accomplish its main objectives.

The group will have to use telescopes, computer simulations and a host of other tools to figure out where debris lies in orbit. Alan Stern, another team member and Southwest Research Institute scientist, said that they may not know whether they need to change New Horizons’ course until “just 10 days before reaching Pluto.” He called the situation “a bit of a cliffhanger.”