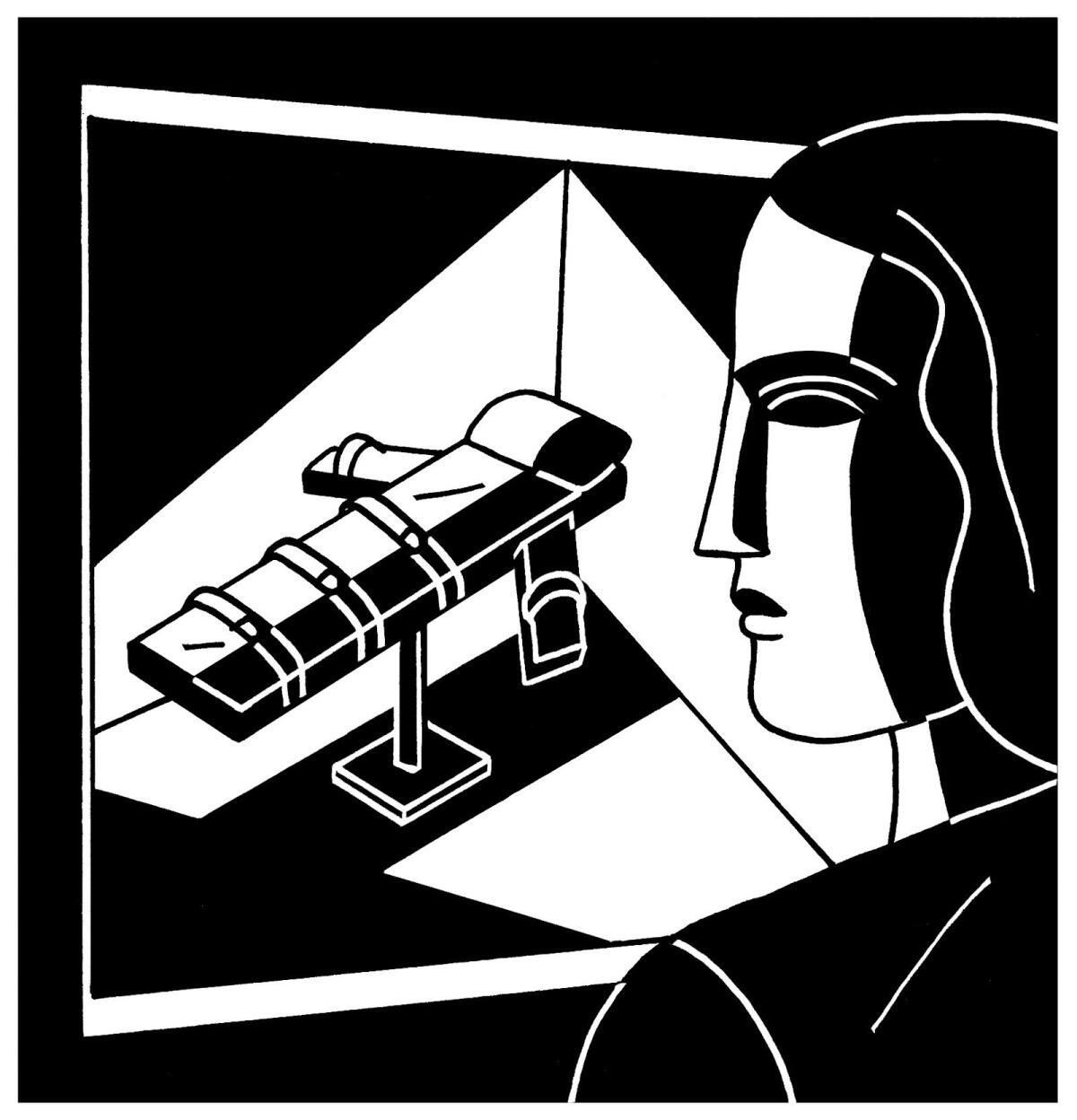

Editorial: Florida case spotlights flaws in the death penalty system

The state of Florida has an odd process for reaching decisions in death penalty cases, one that the U.S. Supreme Court was asked to overturn in a case argued this month.

Timothy Lee Hurst was convicted 15 years ago of robbing and murdering an assistant manager of a fast-food restaurant where he worked, and was sentenced to death. In Florida, as in all but two other states (Louisiana and Oregon), a jury must decide unanimously whether the defendant is guilty. Like other states, Florida also asks the jury to weigh aggravating and mitigating factors in determining whether a person convicted of murder should be sentenced to death.

But Florida juries only make a recommendation; the final decision on whether to impose the death penalty is up to the judge and can be based on factors determined by the judge alone. Hurst argues that violates the 6th Amendment right to a trial by jury.

He may be right. But in this case the question of who ultimately decides is actually less interesting to us than the question of how that decision is reached.

Consider this, for instance: When a jury in Florida sends its life-or-death recommendation to the judge, it weighs aggravating and mitigating circumstances, but then it doesn’t tell the judge which ones it found significant. So as the judge considers whether the crime justifies a death sentence, he or she must do so without knowing how the jury reached its recommendation. Given the profoundly serious nature of the decision, and the fact that the law calls for the judge to consider the jury’s recommendation, that lack of transparency is unacceptable.

Here’s another problem with Florida’s process: The jury is not required to agree unanimously on its recommendation; a simple majority of seven votes is enough to recommend death. In other words, it takes less agreement to recommend death than to convict, even though the death penalty is irreversible. (Also strange is the fact that those jurors don’t have to base their votes on the same aggravating factors, which means death can be recommended even if a majority of the jurors cannot agree on why they’re recommending it.)

On the surface, this case is about fine-tuning the death penalty process. But viewed only slightly differently, it is about the random and indefensible nature of our capital punishment laws.

The reality is that the death penalty is not moral; neither Florida nor any other state has figured out how to carry it out in a fair, just or transparent manner. A series of exonerations in recent years shows that the system is too susceptible to manipulation to be trusted with life-or-death decisions. Further, not only is the death penalty ineffective as a deterrent, it is applied disproportionately to minorities and is often meted out arbitrarily depending on the county in which a murder occurs. It’s a fatally flawed system.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.