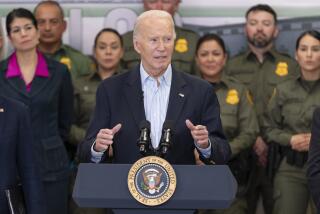

Editorial: Addressing the border crisis

Tens of thousands of Central American children, some accompanied by adults but most traveling alone, have surged across the U.S.-Mexican border in recent months. The flood has swamped the border security infrastructure as well as the youth housing facilities maintained by the Department of Health and Human Services. Under federal law, HHS must take charge of unaccompanied and undocumented minors 72 hours after they are detained by immigration agents.

Now the Obama administration is asking Congress — which can’t agree on what day it is, let alone enact a law — to spend an additional $2 billion to improve the government’s ability to handle the growing problem. The president also wants Congress to change the 2008 federal law that automatically routes minors to immigration court; instead, he wants to let border agents quickly deport those children who can’t make a prima facie case for why they should be let in, a move designed to both lessen the burden on the system and serve as a deterrent to those still hoping to enter.

This humanitarian crisis, which is how President Obama has described it, is both divisive and frustrating, and finding long-term solutions will require a broad and nuanced understanding of the problem. As the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has argued, this is a regional crisis that demands regional solutions — not just more guards at the border or more lawyers in the immigration courts. The United States should be involved in those solutions because it is more than just a wealthy country that attracts illegal immigrants; it bears some responsibility of its own for the violence and instability in Central America.

According to a recent report by the independent, nonprofit International Crisis Group, rivalries between drug traffickers and an absence of governmental control along the Guatemala-Honduras border have made the area among the most violent in the world. Where are the drugs heading? Primarily to the U.S., where most of the demand for marijuana and cocaine comes from. Similarly, the most powerful street gangs in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras are transnational and have their roots in U.S. cities, including Los Angeles. And while drugs are being smuggled north, guns are being smuggled south. More than a quarter-million guns are slipped across the U.S.-Mexico border each year, according to a 2013 study by the University of San Diego’s Trans-Border Institute.

Why does this matter? Because those who have spent time interviewing the unaccompanied minors showing up at the U.S. border report that the vast majority of them say they are fleeing violence and instability in their home countries — primarily Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. The children have described the conscriptions of boys by gangs, and retaliation against the families of those who refuse, including, in some cases, rape. Ironically, U.S. deportations of foreign-born criminals help feed the gangs that are prompting the flow of minors north.

It’s important to distinguish between why someone flees a city and his or her decision on where to go. Once fear of gangs and violence seals the decision to run, the vast majority are choosing the U.S. as a destination, often hoping to reunite with family members who are already there. Many also are lured by misinformation spread by coyotes and traffickers suggesting that children, and mothers with children, can get permisos — permits — to stay. Some misinterpret the June 2012 Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which offers temporary status to some children who arrived before 2007, thinking that they too will be allowed to stay. But in fact, new arrivals are not eligible for the program. And insufficient space in detention centers and youth housing facilities has led immigration authorities to release some young detainees into the custody of relatives or other sponsors, with an appearance ticket for a later court hearing. Thus the rumors of permisos spread.

Significantly, it’s not just children fleeing the instability. The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services reported last week that there has been a sevenfold increase since 2009 in undocumented migrants of all ages seeking entry because they face a “credible fear” of being the victim of violence if returned to their home countries, most of them from Mexico and Central America. So violence as a catalyst for migration has been a long-unfolding problem.

The Obama administration is right to seek humane ways of dealing with the influx, including adding immigration judges, lawyers and others crucial to a speedier deportation process. Sending people back more quickly would also help blunt the rumors of permisos for children. But in addition, the government needs to consider the connections between the American drug users who create the demand that feeds the violent drug cartels, the multinational street gangs and the free flow of illicit weapons across the border.

What can be done? Reducing drug demand and the southward flow of guns would help, as would an increase in U.S. assistance designed to stimulate economic development in Central America, and thus job prospects. The U.S. could expand its work with gang-intervention programs in the Central American barrios. Homeland Security recently moved 60 additional investigators to its anti-smuggling efforts along the Texas border, efforts that should continue and, if needed, increase to break up the human trafficking networks. Everard Meade, director of the Trans-Border Institute, suggests treating the violence surrounding the drug traffickers and street gangs “like the regional armed conflict that it actually is” rather than as a U.S. immigration problem.

Washington can, and should, try to stop illegal immigration at the border, but it would be wiser, and more humane, to find ways to stabilize the communities from which immigrants are running. Any solutions must come with the full involvement and engagement of the governments of Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and Mexico, a challenge given the endemic corruption in those governments. But the U.S. is in the best position to bring the players together and forge the strategic, regional approach to ending this humanitarian crisis.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.