Editorial: Asylum seekers deserve the chance to be heard

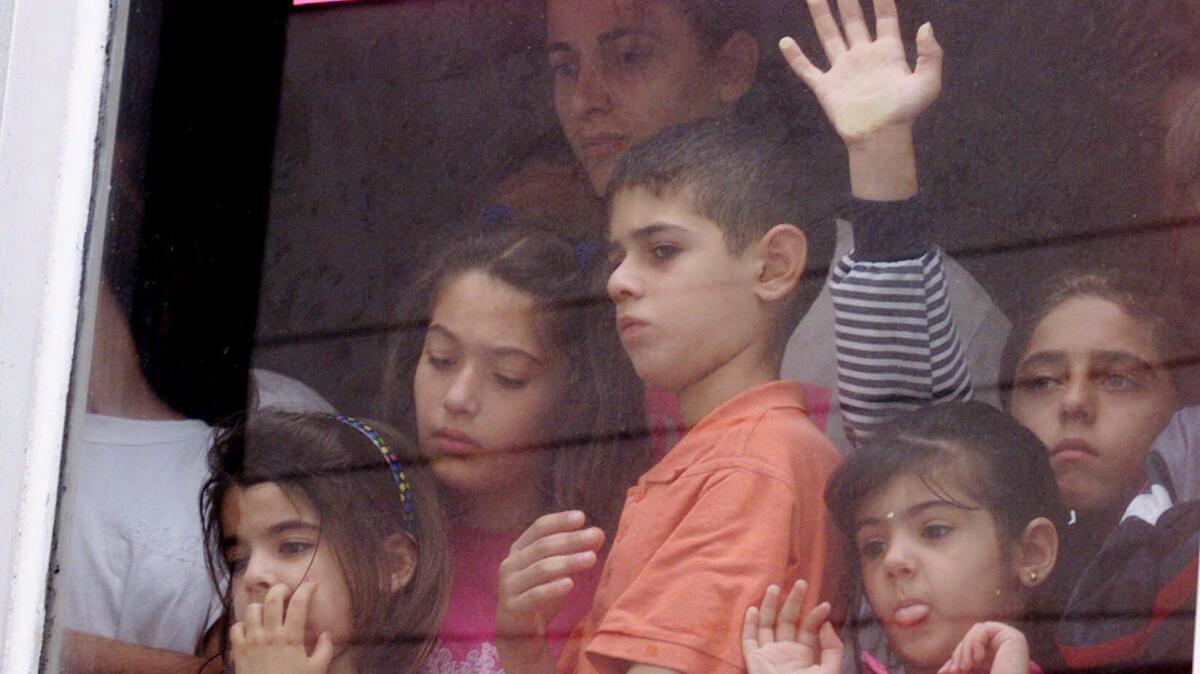

Overwhelmed by an influx of young families and unaccompanied minors fleeing Central American violence, federal immigration officials adopted a “rocket docket” approach two years ago to speed up initial hearings for people caught at the border. The result: faster deportations for recent arrivals who failed to offer a minimal argument that they should be granted sanctuary.

One impetus for the change was to send a message to those still in the Northern Triangle countries of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador that if they undertook the dangerous trip north, they would in all likelihood be quickly sent back home. Immigrant rights activists warned that such an approach risked denying those with legitimate asylum claims the chance to pursue them, and it looks like the critics may have been right — particularly for mothers with children who faced an immigration judge without legal counsel.

A recent report by Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse found that of 38,601 “rocket docket” cases of adults (usually mothers) with children decided from July 2014 through this past September, 70% of those facing deportation didn’t have a lawyer. Of those, 43.4% were ordered deported at their initial hearing, with a median time from filing to closure of 24 days. But among those who found a lawyer, only 4% were ordered out at that initial hearing.

It’s unconscionable that lack of access to legal help forces so many vulnerable people who may have a legal right to stay to instead return to danger.

While the Executive Office for Immigration Review, which operates the immigration courts, disputes some of TRAC’s analysis of federal data, the broad outlines of the report reveal a stunning difference in outcomes. A prime factor in that disparity, according to TRAC, is that only 1 in 15 families without lawyers filed the proper papers to seek asylum, something immigration advocates ascribe to their ignorance of the arcane process. You can’t make a coherent case that you should be allowed sanctuary if you don’t know how the system works.

National governments have a right to determine who enters and who gets to stay inside their borders. But most, including the U.S., have recognized through their own laws and international agreements that people have some form of basic human right to seek refuge from life-threatening conditions in their home country. That usually means nations offering protections to people who are persecuted over faith, political beliefs, gender or other personal traits.

So what is prompting so many Northern Triangle families to flee? Neighborhoods controlled by street gangs that extort “protection” money and threaten to kill young boys or rape family members if they don’t join, abetted by law enforcement systems incapable of stabilizing the neighborhoods. The U.S. bears some responsibility for the disorder. Many of the biggest gangs’ roots trace back to Los Angeles and other American cities, guns used in crimes often are smuggled in from the U.S., and the gangs traffic in drugs destined for American streets.

Whether those conditions are sufficient to grant asylum to those who flee is up to the immigration courts, which are overwhelmed by mounting caseloads. The current record backlog exceeds half a million pending cases despite the recent addition of new judges. But it’s unconscionable that lack of access to legal help forces so many vulnerable people who may have a legal right to stay to instead return to danger.

It’s also distressing that the chances a migrant has of being allowed to stay often depend on which court hears the case. According to the TRAC data, immigration judges in Memphis, Baltimore, Harlingen, Texas, and Dallas ordered deportations during initial hearings for two out of three unrepresented mothers with children, while judges in Orlando, Fla., Newark, N.J., San Francisco, New York and Detroit ordered deportations in fewer than 15% of those cases at the initial hearing. Such a wide swing in treatment suggests fundamental problems with consistent application of the law, which the government needs to address.

The best way to improve the system would be a comprehensive overhaul. And something along those lines may just happen under President Trump and a Republican Congress, although the anti-immigrant tenor of Trump’s campaign and of Sen. Jeff Sessions (R-Ala.), his nominee for attorney general (who would oversee immigration courts), make it hard to imagine that their overhaul would prioritize fairness. Still, we urge the new administration to recognize that an offer of sanctuary is worthless if it comes with unscaleable hurdles. The new administration should work with the attorneys who voluntarily handle immigration cases to devise a system to ensure those with legitimate reasons to seek protection actually get it.

To read the article in Spanish, click here

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.