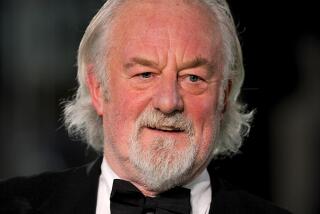

Column: Tobias Capwell, the man who escorted Richard III’s coffin

England’s King Richard III was killed twice: first by his challenger, Henry Tudor, at the battle of Bosworth Field in 1485, and again, in posthumous reputation, by Tudor historians and by Shakespeare, who portrayed the last English king to die in battle as a “bunch-backed toad” and accused him of murdering his young nephews in the Tower of London to become king. Richard’s skeleton was, astonishingly, discovered in 2012 and identified through DNA. It is being reburied in Leicester, England, this week with far more pomp than 530 years ago, when it was dumped into a soon-forgotten grave that was eventually covered with a parking lot. One of the two knights escorting the king on his last journey is Tobias Capwell, born in Petaluma and now a top British medieval military historian — a California Yankee in King Richard’s court.

You and your colleague, in full medieval armor, escorted the king’s coffin in the reburial procession, even on the same bridge where a horse carrying the king’s body had crossed. What a moment for a historian.

There was an extraordinary sense of occasion. I think the most moving moment was when we stood on either side of the cathedral doors and the pallbearers brought the coffin right past us.

How did you get so interested in medieval history that you became curator of arms and armor at the Wallace Collection?

When I was 4 or 5, I had my first visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s famous collection of medieval and Renaissance arms and armor. I walked into the huge hall, lit beautifully by skylights, and it had that profound effect on me. I was hooked. I’m a good example of why you should take children to museums!

And why your interest in Richard III?

From the time I was a teenager, I was taken with the 15th century. The knight as a military and cultural figure was at its height. The Wars of the Roses and especially Richard III were appealing for the same reason they appeal to others: There’s a mystery, and a sense that this person was perhaps quite different from how he was treated by historians.

Shakespeare made Richard into a cartoon villain.

Richard is treated as this black legend, not as a human being. No real person is like that. Real people are more complicated. What is the reality of his situation? Terrible stress, terrible physical danger, danger to one’s loved ones might push a basically honorable person to the edge where he does awful things. That’s what history is about for me: good people doing some pretty awful things, and terrible people sometimes doing pretty decent things. The princes in the tower is one of the most tantalizing parts of Richard’s story, but you mustn’t get bogged down in it. It’s not as if the princes question determines his entire life.

The Middle Ages was a real time, populated by real human beings like you and me, but there are so many layers of fantasy that modern people find it quite alien. For [them], it’s a cartoon land with women with pointy hats and knights who cover themselves in metal. People have a hard time relating to that the way they do to the Second World War, something closer to our own experience. But the Middle Ages is just as relevant.

Today, Richard would be the tough, young CEO whose wife and child died within a year of each other, who had to fight to keep his job and whose friends abandoned him. No wonder he’d have problems.

By the end of his life, he was drinking pretty heavily, his physical fitness had suffered. And he was making decisions that might not only determine the course of his life, but life or death for other people too. In the Middle Ages, huge power was vested in individuals. At the point when Richard may or may not have ordered the deaths of his nephews, he was in an almost impossible situation. Just about anything he did would have had terrible consequences for somebody.

As part of the Richard III Society team, you were at the excavation the day before the skeleton was found. What did you think of the discovery?

I had a hard time accepting it for a while; it seemed so ridiculously improbable. For many people, the big shock was that he had this severe spinal condition, but I love that. Now you see where the black legend comes from. He wasn’t a hunchback. Richard may have successfully hidden his condition, [but] when his body was stripped at Bosworth Field and this twisted spine revealed, that’s when the black legend was born. All that people who want to slander him have to do is exaggerate the truth, and emphasize the typical medieval belief that the exterior appearance of a person is a reflection of inner character.

With the physical evidence, and your expertise in medieval combat, describe how he died.

The injuries he did suffer are evidence he was overpowered, and someone who knew how to deal with men in armor got his helmet off and smashed his skull in. There’s almost no injury anywhere else on his skeleton.

How would the king have been suited up and mounted the morning of Aug. 22, 1485 — the day that would end with his naked body slung over a horse?

His squires would have put his armor on him, covering the body from head to toe in articulated steel plates. His armor probably weighed between 45 and 50 pounds and was fire-gilded, covered in a thick skin of pure gold. He would have looked like the sun in human form.

His horse would also have been wearing steel armor. Richard would have had his sword and dagger and carried his heavy cavalry lance. He would have gone onto the battlefield to command and to join the battle at the point he felt it was right.

It’s an extraordinary thing for a king to lead his men personally, in the front line, to be prepared to live or die as king, as Richard himself said. Can you imagine Barack Obama or David Cameron fighting personally in the Middle East? It hasn’t happened since [George] Washington!

It’s what medieval kings did, at least the good ones. It’s awful and dreadful, but somehow it’s more honest. If you’re going to send young people to their deaths, you need to go with them. The need for the leader to be there personally was an essential part of the medieval way of fighting a war.

What was Richard’s last battle charge like?

He intended to sweep his enemies from the field in a decisive cavalry charge, as a warrior king — a blow that would end all question of his rights as king. Richard always intended to ride down like St. Michael the Archangel and crush the enemy.

Let’s not forget he came within inches of killing Henry Tudor and winning the battle. [He] killed the wrong person. If his spear had been to the left, the Tudor age might never have happened. It was the Tudors who made England a Protestant country, setting in motion events that [sent] pilgrims to the New World — America. If Richard had won, America might never have happened. Or it might have, but in a very, very different way. These small moments that [supposedly] have nothing to do with North America — [but] what America is, where America comes from was determined hundreds of years before.

Why does he still resonate? People around the world have formed Richard III societies.

It’s visceral. He appeals as a champion of the misunderstood and the wronged. The scoliosis is a reminder that he was a real person who was ambiguous.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Twitter: @pattmlatimes

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.