Op-Ed: L.A. has a plan for combating climate change. But is it realistic?

California has had a glimpse in recent years of what it can expect as the climate continues to change: wild swings from extreme drought to extreme rainfall and snowfall, a sharp increase in devastating wildfires and record temperatures.

With poor leadership on climate issues from the federal government, the state has responded to the unfolding crisis by passing ambitious legislation aimed at achieving 100% renewable energy generation by 2045. California will also require solar panels on all new homes starting next year, a doubling of building energy efficiency requirements and a strengthening of the state’s cap and trade program, with an emphasis on investments in greenhouse gas mitigation efforts in disadvantaged communities.

And now, cities are stepping up as well. In Los Angeles, Mayor Eric Garcetti’s recently released Green New Deal commits the city to goals consistent with the Paris climate agreement and beyond.

But are such goals achievable by cities? And are they enough?

The mayor’s vision is compelling. Who wouldn’t want to live in a city with no homeless on the streets by 2028, or one with easy access (a half-mile or less) to fresh food for 100% of low-income residents by 2035? And there is a strong argument that plans have to be bold in order to spur people to action.

Today, the city is less than six years away from being coal free.

In 2012, UCLA, as part of their Sustainable L.A. Grand Challenge, developed what seemed at the time ambitious targets for Los Angeles County and its 88 cities to reach goals that included getting 100% of their energy from renewable sources by 2050. That goal was initially met with skepticism, because the city was still hooked on coal. Today, the city is less than six years away from being coal free. Some 33% of its energy comes from renewable sources, and a workable plan is in place to raise that percentage to 80% by 2036.

The goals in the mayor’s Green New Deal are also attainable, but only with public buy-in and support. The good news is that voters have shown themselves willing to support investment in green infrastructure, passing ballot measures that provide more than $100 billion for electrified public transit, stormwater capture, park acquisition and construction, and supportive housing to reduce homelessness. Still, these funds represent only a down payment on what’s needed to transform Los Angeles into one of the most sustainable megacities in the world.

For example, transformation of the city’s wastewater treatment system into a full water recycling system (part of the path to hitting the mayor’s goal of getting 70% of the city’s water from local sources by 2035) could cost $6 billion to $8 billion dollars, an amount that can’t be simply passed on to ratepayers. Remaking the system would require significant funding from the state and federal government. Similarly, reaching the target of 80% electric vehicles on the road by 2035 can’t be done without significant government support in the form of subsidies, since there are currently more than 7 million gasoline- and diesel-powered vehicles in Los Angeles County, many of which were recently purchased and thus likely to still be on the road in 15 years.

Some of the aggressive energy and local water targets in Garcetti’s plans won’t be achievable without changing laws. Getting businesses and homeowners to retrofit for energy efficiency, for example, will take both new laws and financial incentives. To hit the mayor’s goal of having every building in Los Angeles adding no carbon to the environment by 2050, homeowners would have to swap out their gas stoves and heaters for electric alternatives, which seems unlikely without both incentives and legal requirements. And even then, finding the political will and getting buy-in from residents would be difficult. It was one thing to require low-flush toilets and water-efficient shower heads when houses changed hands; whole new heating and air conditioning systems will be a lot tougher.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute »

One real deficiency in the city plan is its lack of emphasis on ecosystem protection and preservation. Los Angeles lies within one of the 35 recognized biodiversity hot spots in the world. As the United Nations reported two weeks ago, 1 million plant and animal species are on the verge of extinction worldwide, and natural ecosystems have declined an average of 47% compared to their earliest estimated status. What is unique about the U.N. biodiversity report is that it links this loss of species and habitat directly to human activity.

Garcetti’s plan commits to stopping further loss of native species and creating a development of a biodiversity index. But it does not call for increasing protected natural areas or greater habitat connectivity to provide more wildlife corridors. These are critical regional needs that would protect our extraordinary biodiversity, enhance ecosystem services and improve human habitable environments and our quality of life.

Still, the plan is a huge step forward. There is little time left to address the planet’s climate crisis, and without ambitious blueprints like the one the mayor has put forth, humanity will never make the necessary financial investments, pass the necessary legislation, change our wasteful culture of consumption and shift to a greener, less-polluting economy.

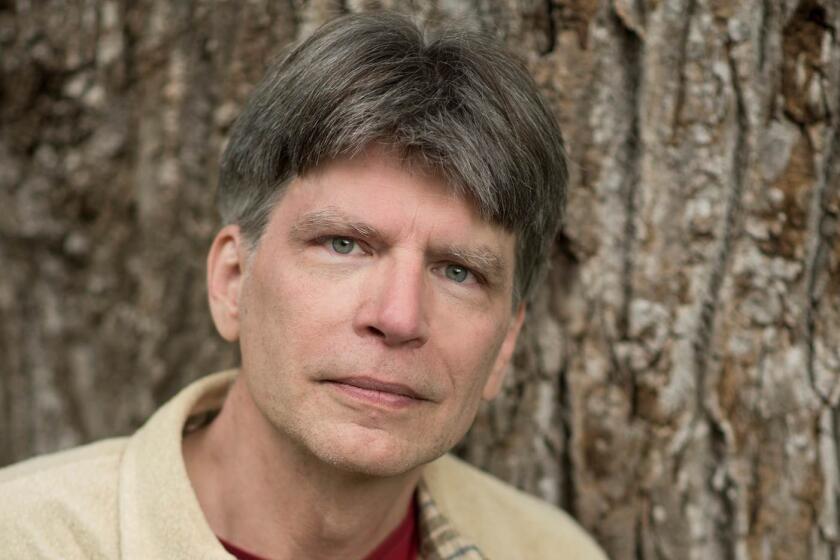

Mark Gold is associate vice chancellor for environment and sustainability at UCLA.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.