Opinion: Jonah Goldberg and the GOP’s Harry Reid obsession

Times columnist Jonah Goldberg swings his rhetorical hammer Tuesday at congressional dysfunction, arguing that polarization wasn’t as big a problem as politicians’ eagerness for self-protection.

It’s a good point, and his column is very much worth reading. But while Goldberg reaches the right conclusion -- that politicians hurt themselves by ducking votes on divisive, politically sensitive issues -- he trips over his own feet in getting there.

He blames one guy in the Senate -- Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) -- while absolving the GOP leadership in the House of any culpability for doing essentially the same thing.

Let me make something clear up front: Reid hasn’t been a successful majority leader, and he’ll deserve some of the blame if Democrats lose their majority. He’s been the Senate’s top officer over six of the most contentious, least productive years in recent memory. Some of his predecessors were equally partisan -- George Mitchell (D-Maine) comes immediately to mind -- but none had as much trouble getting things done as Reid has.

But Reid isn’t a dictator who can defy the will of his chamber, regardless of what his critics on the right contend. And while Goldberg rightly points out that Reid’s (dubious) strategy has been to protect members from “tough votes,” such as whether to approve the Keystone XL pipeline, he ignores the crucial role that Republicans and other Democrats play in that strategy.

For their part, Republicans have routinely sought votes on measures that have no chance of becoming law because of strong opposition by Senate Democrats or President Obama. The ultimate fate of the amendments is irrelevant to them; the point is to win elections, not to make laws. And they’re helped in that endeavor by Senate rules that let members offer non-germane amendments, meaning that a bill on student loans can become the platform for a debate on Keystone XL or arming Syrian rebels.

This isn’t a new tactic, and contrary to Goldberg’s assertion, Reid’s response -- to block the GOP’s ability to offer amendments -- is hardly “wildly partisan and nearly unprecedented.” The tactic is called “filling the amendment tree,” and Mitchell did it any number of times during his tenure. Republican leaders have done it as well.

What’s unprecedented is how frequently Reid has filled the tree. Goldberg’s probably right about the price Democrats will ultimately pay for this tactic. But to blame Reid is to blame the messenger. As Goldberg points out, the vulnerable Democrats who are likely to be hurt most by this approach cast the votes necessary to put it into effect. If Senate Democrats didn’t want Reid to do what he’s been doing, he wouldn’t be majority leader.

(The same has often been said about House Speaker John Boehner [R-Ohio], who has often found himself constrained by a few dozen members aligned with the tea party.)

Granted, the Senate majority leader is the most powerful member of that body, thanks to Senate rules and customs that allow him to take the floor first and decide which bills to seek action on. Yet Senate rules allow every other member to offer almost any other piece of legislation as an amendment on virtually any bill. They also allow the minority to block the Senate from voting on or even taking up a bill, and a single member to block consideration of a bill that wasn’t on the Senate calendar (e.g., a bill that hasn’t been reported by a Senate committee or sent over by the House).

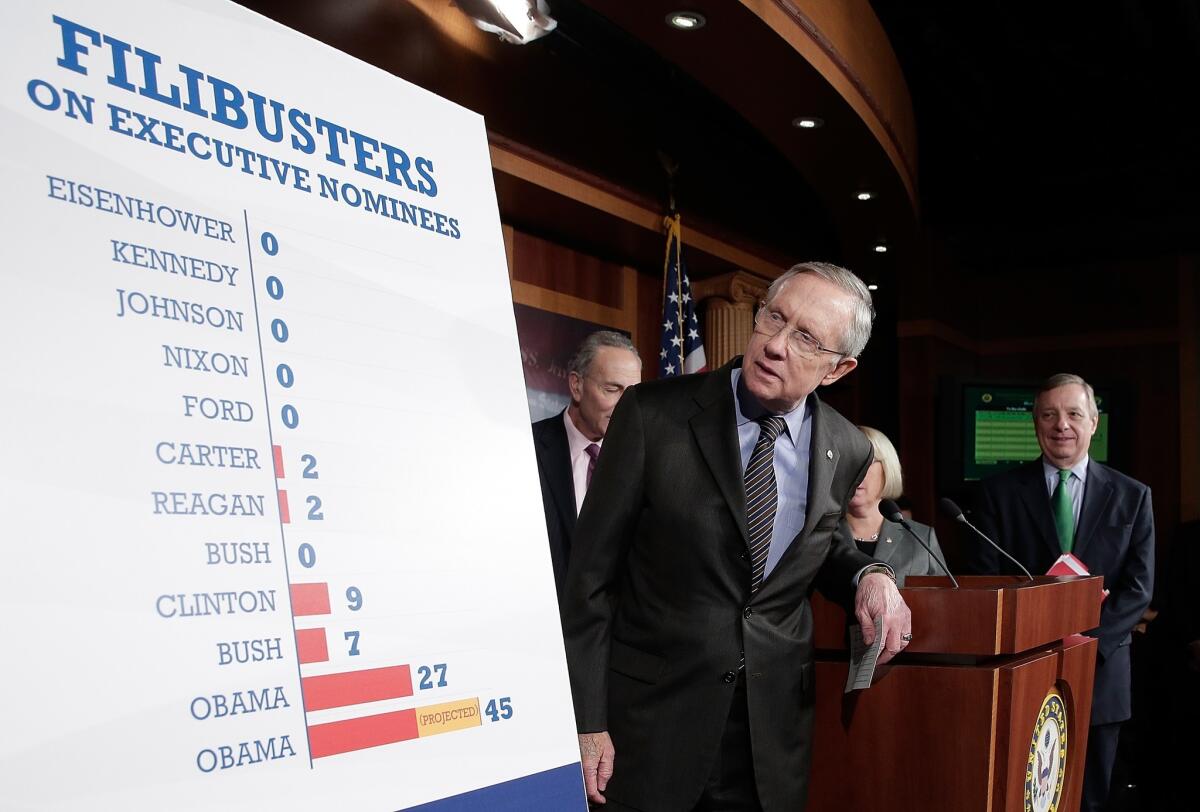

This fluidity makes it difficult for the Senate to act without consensus, which is as valuable as it is frustrating to those trying to make the federal government work. It also opens the door to the sort of scorched-earth tactics on both sides that led the Senate to where it is today, with Republicans constantly waging filibusters and Reid routinely blocking almost all amendments.

The House, by contrast, does not permit members to offer non-germane amendments. It also lets the majority, which has total control over what measures and amendments reach the floor, set special rules for debating each bill. Those rules may constrain the minority even more severely than the standing rules of the House do -- as has happened at least twice in the current Congress.

Goldberg notes that House Republicans have dodged tough votes too. They’re actually a lot more reluctant to take votes that test GOP unity than Goldberg acknowledged; the Republican leadership almost never brings legislation to the floor unless more than 90% of the party supports it. But Goldberg doesn’t blame Boehner for that, or even his leadership team. He blames House Republicans collectively.

The same logic applies to Senate Democrats. Reid isn’t a puppet master, he’s the guy who figures out how to give as many of his members what they want. And while there’s plenty of grumbling from Democrats about the inability to offer amendments, they support Reid’s tactics because they believe avoiding tough votes is the best way to hold onto power. Although we’ll find out for sure next week whether this was the right approach, the polls suggest otherwise.

So why demonize Reid? Because when you’re trying to defeat an incumbent who’s built up a large base of support over the years, it helps to have a distant and easily caricatured figure to campaign against. Not that Republicans really need one this time, considering how much material Obama has given them to work with.

Allowing more votes on disputed issues wouldn’t necessarily have led to a more productive Congress. The vast majority of the measures that Senate Democrats didn’t vote on were pure GOP fantasies, such as ending Obamacare, gutting the Clean Air and Clean Water acts, and creating new permanent tax breaks without paying for them. But the steps Reid took to block those votes only made the gridlock in the Senate worse, barring the sort of give-and-take on the floor that enables compromise (assuming, of course, that anyone on either side really wants to compromise). And that intransigence is one of the main reasons why so many voters think so poorly of Congress.

Follow Healey’s intermittent Twitter feed: @jcahealey

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.