Opinion: Want to be seen as smarter and more important? Use a middle initial.

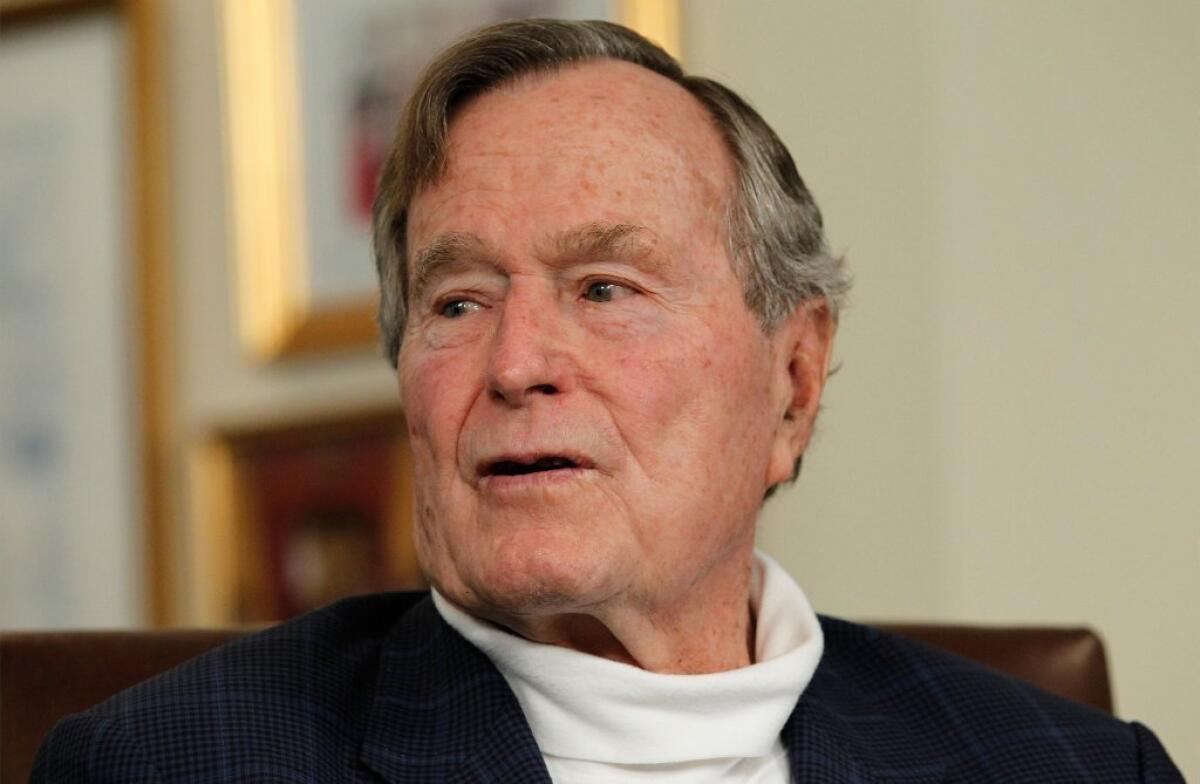

As president, he was George Bush, but when his son was elected, stories began referring to him as George H.W. Bush.

I briefly took on a new identity the other day. For most of my career, my byline — when I have one; the editorials I write are unsigned — has been “Michael McGough.” But as part of the relaunch of The Times website, there is a new configuration for bylines, and the other day I noticed that one of my blog posts had appeared under the byline “Michael P. McGough.” (That’s how I sign my checks.)

I corrected the error, but maybe I should have let it go. According to a study published in the European Journal of Social Psychology, the use of middle initials by some people “increases the perceived social status of these people and positively biases inferences about their intellectual capacity and performance.”

The coauthors of the article were Wijnand A.P. Van Tilburg of the University of Southampton and Eric R. Igou of the University of Limerick. Van Tilburg is presumably the more prestigious of the authors, since he has two middle initials. That’s a common usage in Britain but mercifully rare in the more democratic U.S. Newspapers didn’t start referring to former President George H.W. Bush until after the election of his son George W. Bush.

According to a story about the study on the Pacific Standard website:

“The first [study] featured 85 students from the University of Limerick, who were asked to read a short article describing Einstein’s theory of general relativity, and evaluate how well it was written. The author of the text was presented as David Clark, David F. Clark, David F.P. Clark, or David F.P.R. Clark. The results: ‘David F. Clark’ received higher marks than ‘David Clark’ with ‘David F.P.R. Clark’ scoring even higher. ‘It seems that one middle initial is sufficient to produce the middle initials effect,’ the researchers write.”

What’s so magic about a middle initial? The researchers offer several explanations of its power. One is that people are impressed by the fact that professionals such as doctors and lawyers use their middle initials in formal correspondence. Another, to me less plausible, theory: that “social groups with habits of giving their children more middle names have overall more resources available for education.” Really? It doesn’t cost anything to add a middle name to a birth certificate.

My parents weren’t rich, but that didn’t stop them from bestowing middle names on all six of their kids. My two brothers and I were given names with the same initials: M.P. — Michael Patrick, Matthew Paul and Martin Philip.

When my mother was expecting her sixth child, she assumed that it would be another boy and she toyed with a variety of M.P. names, including “Murray Peter.” “Murray” was her maiden name, but my father worried that “Murray” as a first name would strike a strange note. He thought “Murray McGough” sounded like a Hollywood agent.

As it happened, child No. 6 was a girl, my sister Megan (official name: Margaret Ann).

Speaking of my mother, when I got my first byline as an intern for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, she was disappointed that it was the no-frills “Michael McGough.” Like the students at the University of Limerick, she thought a middle initial would add a little gravitas. But the byline she really wanted me to adopt was “Michael Patrick McGough,” which I rejected as ethnic overkill. Besides, as an English major, I liked the fact that my byline was metrically symmetrical: a trochee followed by an iamb.

But if Van Tilburg and Igou are correct, I sacrificed prestige for poetry.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.