Flush with a new Nobel, the LIGO team parties at Caltech

In some ways, it was a typical Southern California scene.

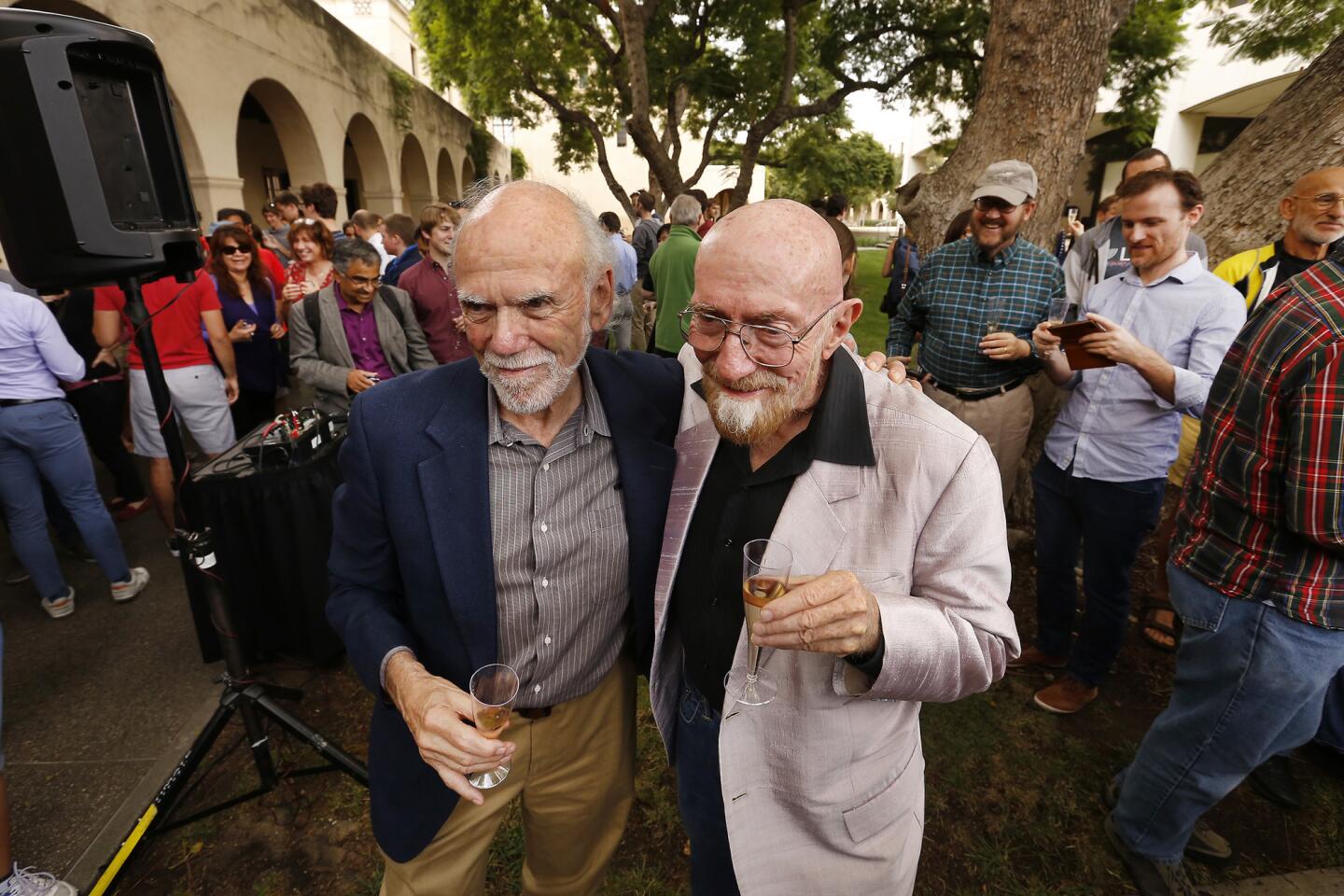

Late Tuesday morning, two men found themselves surrounded by an entourage of friends, family and publicists and preceded by a gaggle of photographers running backward and cameras clicking at a furious pace.

Onlookers whispered to each other as the procession passed them by. Some pulled out cellphones to capture pictures of their own.

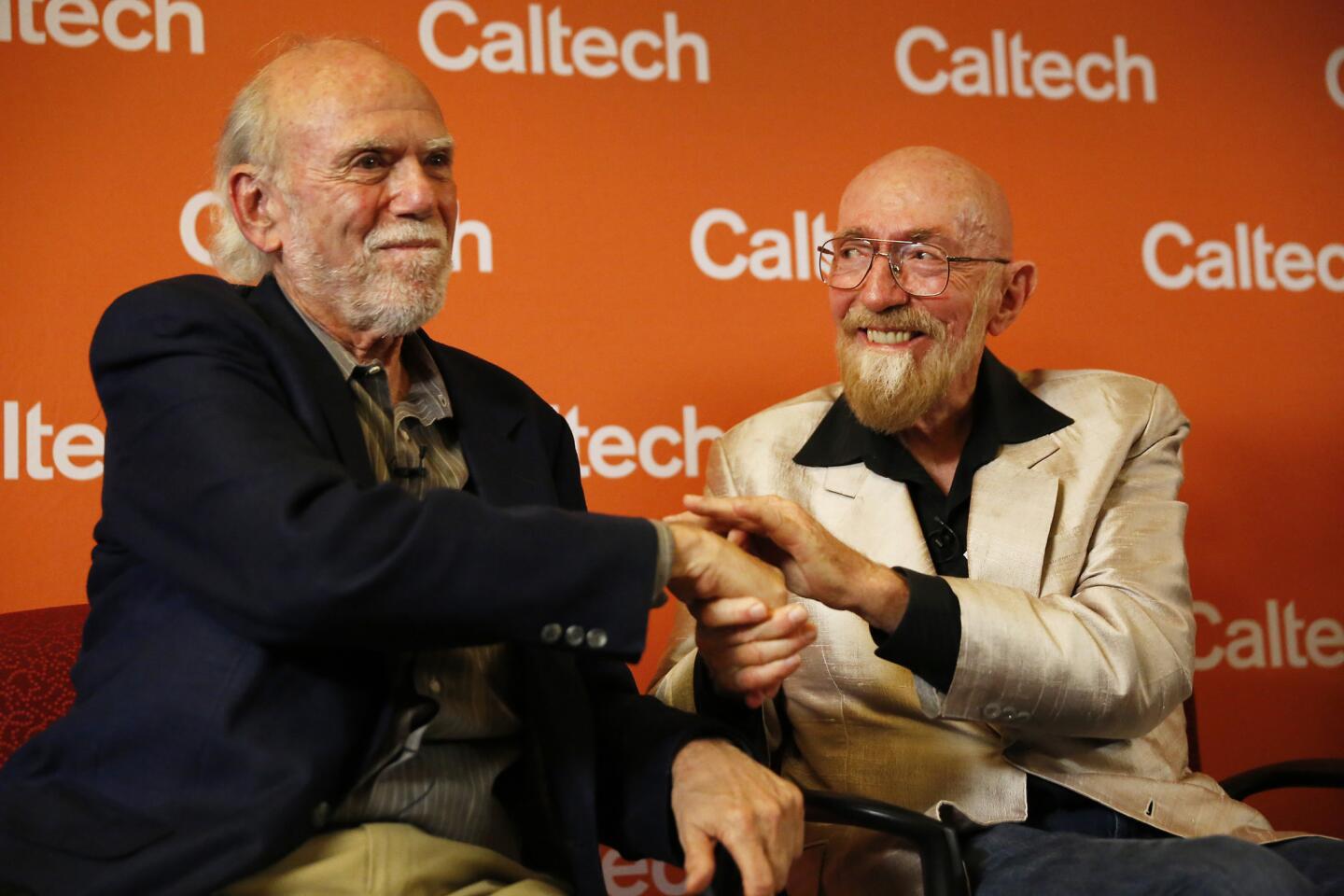

But the older gentlemen at the center of the fray — Kip Thorne and Barry Barish — aren’t your typical L.A. celebrities. They are Caltech scientists who had just been awarded the Nobel Prize in physics.

“These guys are like gods to me,” said Deepan Kishore Kumar, a fourth-year doctoral student at the Pasadena university who woke up at 3:45 a.m. so he could watch a livestream of the Nobel announcement from Stockholm. “They opened up our eyes to a new way to look at the universe,” he said.

Thorne and Barish, along with MIT theoretical physicist Rainer Weiss, received the Nobel for their work on a project called LIGO, which stands for Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory.

It is one of the most high-tech machines ever built by mankind. And there are two — one in Livingston, La., and another in Hanford, Wash.

LIGO is designed to measure gravitational waves, which are incredibly small ripples in the fabric of space-time. These waves are caused by cataclysmic events in the universe.

Its instruments are so sensitive that they can detect movements as small as 1/10,000 the diameter of an atomic nucleus, said Stanley Whitcomb, chief scientist for the project.

Caltech physicists Kip Thorne and Barry Barish, talk about winning the Nobel for their work on a project called LIGO, which stands for Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory. (Video by Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)

“LIGO is one of the most complex experiments ever conceived,” said David Reitze, executive director of the LIGO Laboratory, which comprises about 180 scientists working at Caltech, MIT and the two observatories. “When I first heard about it in 1995 I thought to myself, ‘This is crazy. It’s never going to work.’”

But it did. On Sept. 14, 2015, LIGO’s instruments made the first direct observation of gravitational waves. They were created by two black holes that smashed into each other and merged 1.3 billion years ago.

The two LIGO observatories have subsequently detected three more gravitational waves, all caused by merging pairs of black holes.

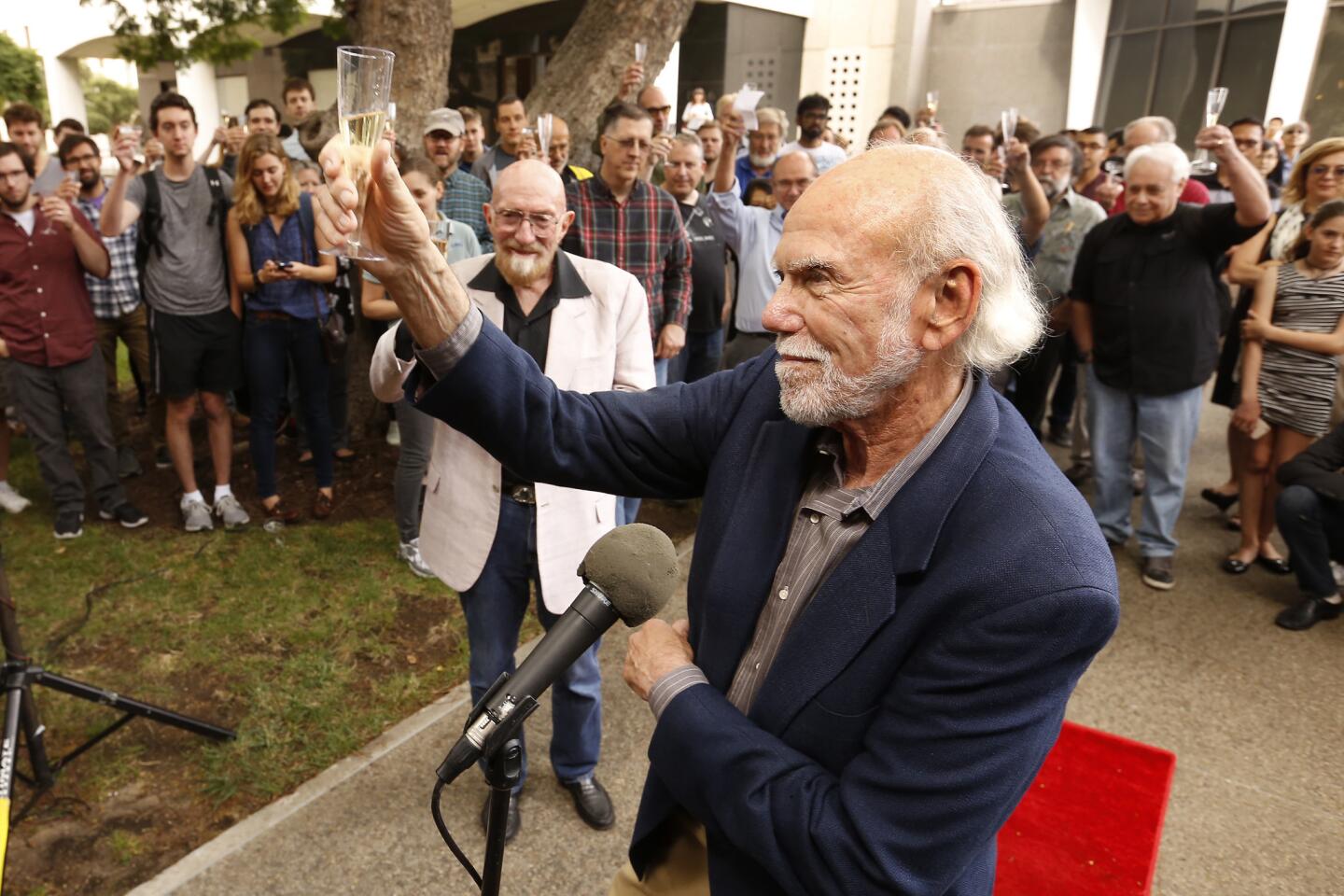

After a news conference in Caltech’s ornate faculty lounge, Thorne and Barish were feted at a champagne-and-cake party with members of the LIGO team just up the hill from the university’s famous turtle pond. Admirers from Caltech’s physics, math and astronomy departments attended as well.

One student hummed a wedding processional as the two men appeared, which somehow seemed appropriate.

Thorne, dressed in a flashy gold jacket and blue jeans, noted that more than 1,000 scientists from around the world had worked on LIGO and that the award belonged to them as much as the three official recipients.

“I’d like to salute the members of LIGO and thank all the people whose thoughts we borrowed and utilized over the years,” he said.

Among the champagne-sipping celebrants were Jameson Rollins, Gautman Venugopalan, Johannes Eichholz and Aidan Brooks, all members of the LIGO team.

They had risen at 3 a.m. to see if their project would win the award. (Venugopalan, the only grad student in the group, said he was up anyway — working.)

“I didn’t know if we were going to get it,” Brooks said. “I was watching it and it was like, ‘Swedish, Swedish, Swedish’ and then ‘Ray Weiss,’ and then I knew.”

Reitze, who had not been able to fall back to sleep after his wife gave him the news about 4 a.m., said that everyone in the LIGO group was thrilled that the experiment had won.

“We all did it,” he said. “And we are all very proud.”

Do you love science? I do! Follow me @DeborahNetburn and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE