One of these plagues is not (genetically) like the others

To plague aficionados, the Justinian Plague, which in the 6th century AD is thought to have killed 30 million to 50 million from Asia to Africa to Europe, is hardly a footnote. But it is a mystery, deepened by a new finding that the bacterium that caused it -- a different strain than that which caused the Black Death and later plague outbreaks -- appears to have gone extinct or is hiding, unseen, in rodent populations.

We will likely never see it again, said the authors of a study published this week in the journal Lancet Infectious Diseases. But they warned there is a lesson in the fact that a strain of plague could jump from rodents to humans, spread, prosper and kill some 40% of its victims for two centuries, and then mysteriously disappear. New and equally virulent pathogens could appear just as mysteriously, they wrote.

“Fortunately, we now have antibiotics that could effectively be used to treat plague,” said study coauthor Dave Wagner of Northern Arizona University’s Center for Microbial Genetics and Genomics. That, he says, “lessens the chances of another large-scale human pandemic.”

The symptoms that overtook victims of the Justinian Plague were described by the early scholar Procopius in terms that echoed 800 years later with the outbreak of the Black Plague. As it took its toll across the known world, it contributed to the end of the Roman Empire and marked the transition from the classical to the medieval period.

The sleuthing reported in the Lancet was as remarkable as the findings themselves. An international team of researchers extracted DNA fragments from the teeth of two plague victims who were buried sometime between AD 504 and 533 in Bavaria, Germany. The authors of the study reconstructed the genome of the pathogen that felled both victims, and compared its sequences with those of more than 100 strains of bacteria from the same family that are currently found in animal reservoirs and humans throughout the world.

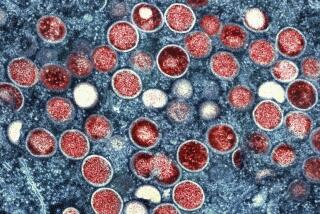

They found that the infectious agent that caused the Justinian Plague is a member of the bacterial family Yersinia pestis, from which sprang the Black Plague 800 years later, and a recurrence of that plague in the late 1800s and early 1900s. But the genetic fingerprint of the Black Plague is sufficiently distinct from the Justinian Plague that researchers concluded it is highly unlikely that they are related, or that one of the Justinian strains evolved into the strains that caused the “Black Death.”

“The strains of Y. pestis in the Plague of Justinian form a novel branch on the Y. pestis phylogeny,” the authors wrote. That novel branch appears to have reached “an evolutionary dead end,” they wrote. It is “either extinct or unsampled in wild rodent reservoirs.”

Among the most discernible chromosomal differences between the strains were two that are associated with a pathogen’s ability to spread, replicate and kill its hosts. The Justinian Plague appeared to have been even deadlier to its victims than the Y. pestis strains that reemerged 800 years later.

After dispatching so many souls in eight-to-12-year cycles with such efficiency, what became of that novel strain? For now, the authors can only conjecture that either human populations evolved to become less susceptible to its deadly ways or that climatic changes taking place at the time created a less hospitable environment for the Justinian Plague pathogen.

Evidence for the latter possibility includes the fact that all three plagues -- the Justinian Plague, the Black Plague and the plague that surged in the late 1800s and early 1900s -- followed periods of exceptional rainfall and ended periods of climatic stability.