Researchers claim stem cell advance

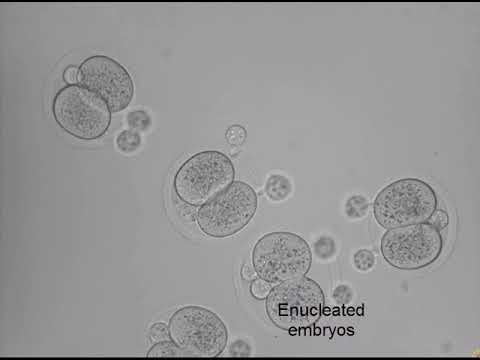

A demonstration of micromanipulation techniques involved during enucleation (removal of the nucleus) and donor nucleus introduction. Credit: Mitalipov Laboratory at OHSU.

As new revelations further discredit a highly publicized Japanese study on the use of acid to create so-called STAP stem cells, scientists in the U.S. have quietly announced a research breakthrough that involves a more traditional means of producing the amazingly versatile cells.

In a paper published Wednesday in the journal Nature, researchers said they had successfully generated embryonic stem cells using fertilized mouse embryos -- a feat that many scientists had thought was impossible.

If the technique is found to work with human cells, it could open up new resources for stem cell production and hasten their use in a broad range of medical applications, including the repair of damaged organs and spinal cords.

Senior study author Shoukhrat Mitalipov, a cell biologist at Oregon Health and Science University, says his lab now wants to reproduce their success, “first in a monkey and later with human embryos.”

If successful, the development would allow the use of “excess” human eggs that are retrieved and fertilized during in vitro fertilization treatments, but never used.

“This is certainly significant,” said James Byrne, an assistant professor of molecular and medical pharmacology at UCLA, who was not involved in the research.

“I think we’re looking at tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, of embryos that are constantly being discarded,” said Byrne, who also studies stem cells at the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research. “This paper now unlocks the ability to use those embryos for better understanding.”

Wednesday’s announcement came just a day after further doubts arose about an unrelated Nature study involving the creation of stem cells through a process called “stimulus-triggered acquisition of pluripotency.” Officials at Japan’s RIKEN research institute acknowledged that strains of mice used in STAP cell research were incorrectly identified, according to the Asahi Shimbun.

While the mouse mix-up doesn’t disprove the existence of STAP cells, it does raise even more questions about the level of care researchers exercised in their work. Earlier this month, RIKEN confirmed two instances of what it called “inappropriate” behavior by researchers, after one study author demanded that the paper be retracted.

The matter remains under investigation by RIKEN and Nature.

The recent study by Mitalipov and his colleagues uses a very different and long-established method of cloning -- somatic cell nuclear transfer, or SCNT. That’s when scientists enucleate, or remove the nucleus from, an egg cell, then replace it with the nucleus of an entirely different type of cell from another organism.

In a phenomenon that scientists do not fully understand, the egg cell’s cytoplasm transforms, or reprograms, the foreign nucleus and causes it to behave like an egg cell nucleus.

Once scientists trigger the egg’s growth in the lab, it will develop into an embryo, and may even be carried to birth if implanted in a surrogate mother. However, the offspring will carry the exact genetic blueprint of the animal that “donated” the transplanted nucleus.

It’s this process that was used to clone the first sheep, “Dolly,” and it has been used to clone a variety of other animals.

But if the embryo is not implanted in a surrogate, scientists can grow the egg into a cluster of cells called a blastocyst. The cells in the interior of that cell cluster are stem cells -- cells that can form any type of cell in the body.

Up until now, researchers had assumed that successful SCNT required the use of immature, nonfertilized egg cells, or oocytes, that had to be arrested in a very specific state of development. If an egg cell had been fertilized, and began to divide, scientists believed it was unusable.

Mitalipov and his colleagues, however, succeeded in using fertilized eggs that had cleaved into two cells. After replacing the nucleus of each cell, the researchers were able to produce living mouse clones that bore the genetic makeup of the transplanted nuclei.

“In view of of the present results ... SCNT into human two-cell embryos with proper cell matching should be reconsidered,” the authors wrote.

Stem cells differ from other specialized cells in the body, because they have the ability to transform into a variety of cells. Scientists envision a day when they are used to regenerate failed organs and treat such ailments as Parkinson’s, heart disease and diabetes.

The process of getting to that point has been fraught with many obstacles, however.

UCLA’s Byrne said that obtaining human oocytes has always been difficult for practical, legal and ethical reasons. Therefore the ability to use two-celled fertilized embryos would open up large research possibilities.

“There are huge amounts of material available, in the way there wasn’t available with oocytes,” Byrne said.

Byrne said he hoped that research involving human embryos would yield lessons that could be combined with the production of induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPS cells, a process that does not involve embryos.

“We may be able to incorporate the advantages of both methodologies and produce cells with more clinical relevance to the patient,” Byrne said.