Nobe Kawano, longtime Dodgers clubhouse manager, dies at 95

There wasn’t much place in professional baseball — not in the 1930s — for a pair of Japanese American brothers who loved to play the game.

So Yosh and Nobe Kawano found another way to make themselves fixtures in the major leagues, spending the better part of five decades as clubhouse managers.

Season after season, they ordered shoes for the players and laid out food before games. They cleaned uniforms, sorted mail and swept the floors. Yosh tended to the Chicago Cubs; Nobe served the same role for the Dodgers.

“It’s pretty amazing, when you think about it,” Ryne Sandberg, the former Cubs second baseman and Hall of Famer, once said. “All the time they spent around the clubhouse, they probably saw everything.”

Late last month, Yosh died at 97 after a long battle with Parkinson’s disease. On Friday, days after attending his brother’s funeral, Nobe died at 95 of respiratory problems.

“Baseball was everything to them,” Nobe’s son, Frank, said.

Moving from Seattle to Southern California at a young age, the Kawanos got their start in pro baseball by accident, when a teenage Yosh was caught stowing away on a boat to Catalina Island.

Also on board was a Cubs executive headed for the team’s training camp. The executive suggested putting Yosh to work shining shoes for ballplayers, the Kawano family recalled.

This penance led to a job with the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League. In the years that followed, Yosh switched to the Chicago White Sox.

During World War II, the Cubs heard that Yosh had been sent to an internment camp and negotiated his release so he could work as a clubhouse assistant. When Japanese Americans were allowed to enlist in the military, he served in the Pacific while Nobe — classified as 4F — joined the U.S. Merchant Marine.

After the war, Yosh returned to the Cubs and Nobe was hired by the Stars before catching on with the Dodgers.

In Chicago, Yosh was known for his meticulous bookkeeping. In those days, clubhouse managers paid for the food and had to collect from players. Yosh made extra cash by selling them gloves, cleats and socks.

Each transaction was recorded, to the penny, and kept in an envelope.

“A guy would get traded away but Yosh would still keep that bill,” Sandberg said. “He’d catch up with the player, sometimes years down the road, and say, ‘Oh, by the way, you still owe me $16.70.’ ”

In Los Angeles, many of the best-known stories about Nobe involved pitcher Sandy Koufax.

In 1960, Koufax suffered through an uncharacteristic 8-13 season. Frustrated, the future Hall of Famer tossed his gear into the garbage, vowing to return to college to study architecture.

The next spring, after his temper had cooled, he reported to camp at Vero Beach, Fla., and found all his things stacked neatly in his locker. Nobe had picked them out of the trash.

“I thought you might need this,” the clubhouse manager said.

Another time, Nobe put out bagels for the Jewish pitcher and heard about it from another player who yelled: “These doughnuts are stale.”

After retiring, the brothers spent their final years together in a Lincoln Heights nursing home, their stories kept alive by relatives because dementia had largely robbed them of the ability to communicate.

By then, the Cubs had renamed their clubhouse in Yosh’s honor and the Hall of Fame had requested one of the floppy hats he always wore.

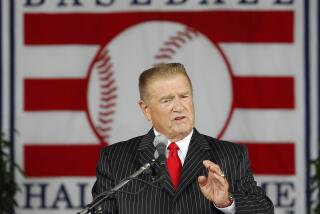

Rick Monday, who played in Chicago and Los Angeles, and is now a Dodgers broadcaster, spoke about Nobe’s status with the Dodgers, recalling an incident after a game in Pittsburgh.

Nobe almost never rode on the team bus — he often stayed at the ballpark late to finish his chores — but as the players returned to their hotel, they spotted him.

“We’re crossing the bridge to go downtown and, at a red light, we pull right behind a city bus,” Monday said. “I look up and Nobe Kawano is on that bus. He took a city bus.”

At the next stop, the outfielder jumped out to retrieve Kawano, saying: “You’re a Dodger. You travel with us.”

“When he got on, all the guys started clapping,” Monday said. “It was a real ovation and he started to giggle.”

Follow @LAtimesWharton on Twitter

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.