A visit to London’s cemeteries

LONDON — What are the first sights you seek when you travel to a new city? The museums? The top restaurants? Or the cemeteries? I choose cemeteries. Although some people think that’s weird, I find them a through-the-looking-glass way of understanding a place and how it grew. They are fascinating, beautiful, a bit mysterious but rarely ghoulish or spooky.

Because of its rich history, London is one of the best cities for touring cemeteries. I started at Bunhill Fields, close to the City, as London’s financial center is called. The name probably comes from the Saxon meaning Bone Hill, although officially this cemetery dates from the 1660s, a time of plague in London.

John Bunyan of “The Pilgrim’s Progress” lies here on top of his high sarcophagus staring up to heaven. Opposite stands an obelisk to Daniel Defoe, who wrote “A Journal of the Plague Year,” one of the first nonfiction novels. The headstone for William Blake and his wife, Catherine Sophia, is nearby. When both were alive, Catherine was heard to complain, “I have very little of Mr. Blake’s company. He is always in Paradise.”

Under the towering plane trees (similar to L.A.’s sycamores), which were planted because they could withstand polluted air, are orderly lines of simple grave stones fenced off from the office workers eating their lunches.

Bunhill Fields looks fine now, but in the early 19th century it was squalid and overcrowded. Across the English Channel, the French had shown the way forward in 1804, when Napoleon ordered all burials in Paris moved outside the city. The result was the great Père Lachaise, the gold standard for modern cemeteries. Tardy London followed suit in 1832 by creating the so-called Magnificent Seven, seven spacious cemeteries ringing the city.

Kensal Green, in northwestern London, was the first to be built outside the new cordon sanitaire. I took the Tube out to the end of Harrow Road on London’s ugly urban fringes, then walked around the cemetery’s high perimeter wall to its grandiose neoclassical entrance.

My great-grandfather, a well-known architect, is buried here, and the first time I visited I was looking for his tomb. Given the Victorian taste for stone angels, sculptures of faithful animals and exotic Egyptian temples, I was expecting something spectacular for him.

Instead, I got a large slab of dark stone surrounded by blood-colored granite and topped with a skewed cross. Kensal Green’s damp clay soil has caused many graves and mausoleums to tilt over the years.

Joe Hughes, a volunteer with Friends of Kensal Green, showed me around when I returned last summer. “Look and see how many different draped urns [Roman symbolism for death] you can see,” he told me.

Seemingly everywhere I looked there were urns, some big, others small, decorated or plain — an endless profusion among the trees.

Kensal Green was an instant success in its day. The Duke of Sussex, the sixth son of George III, chose to be buried here. So did his poor sister Princess Sophia, who had fallen in love with an equerry (a horse officer) and had a son — news that was kept from George III. The Duke of Cambridge, George III’s grandson, is buried in an Egyptian mausoleum with his actress mistress and several of their children.

No major English cemetery would be complete without its poets and littérateurs. William Makepeace Thackeray is buried here with his mother and with the wrong date for his death (Dec. 21, 1863 instead of Dec. 24, 1863). Iron bollards and chain surround his slab. Amazingly, they survived World War ll, when much of London’s ornamental ironwork was melted down for armaments.

Oscar Wilde has the honor of lying in Père Lachaise, but Wilde’s mother and sister are in Kensal Green. So are novelist Anthony Trollope; Wilkie Collins, buried alongside Caroline Graves, one of his mistresses and the model for “The Woman in White” and, most recently, playwright Harold Pinter.

I had never visited Brompton Cemetery, the most central of the Magnificent Seven. It turned out to be an acre of quiet in the middle of London that joggers and lovers, cyclists and dog walkers frequent.

Brompton, a flat rectangular site designed as a miniature of St. Peter’s in Rome, has avenues of trees instead of pillars, both formal and enchanting. The day I went, the air was scented with lime blossoms, overwhelming, sweet and slightly repulsive, much like a Victorian cemetery. Stone doves competed with flapping pigeons for space on top of Woolley’s Mausoleum. Crosses entwined with stone and real ivy looked very romantic.

It was easy to find the Celtic cross commemorating Emmeline Pankhurst, the suffragette. Then there were the lions. I’m a sucker for stone lions, and Brompton has a particularly mournful one atop the tomb of “Gentleman” John Jackson, the prizefighter.

The next day, I was on the Tube traveling to the pièce de résistance among the seven — Highgate, in the eponymous, leafy northern London suburb. Highgate Cemetery is in all the guidebooks, and even those who don’t share my interest in cemeteries have heard of it.

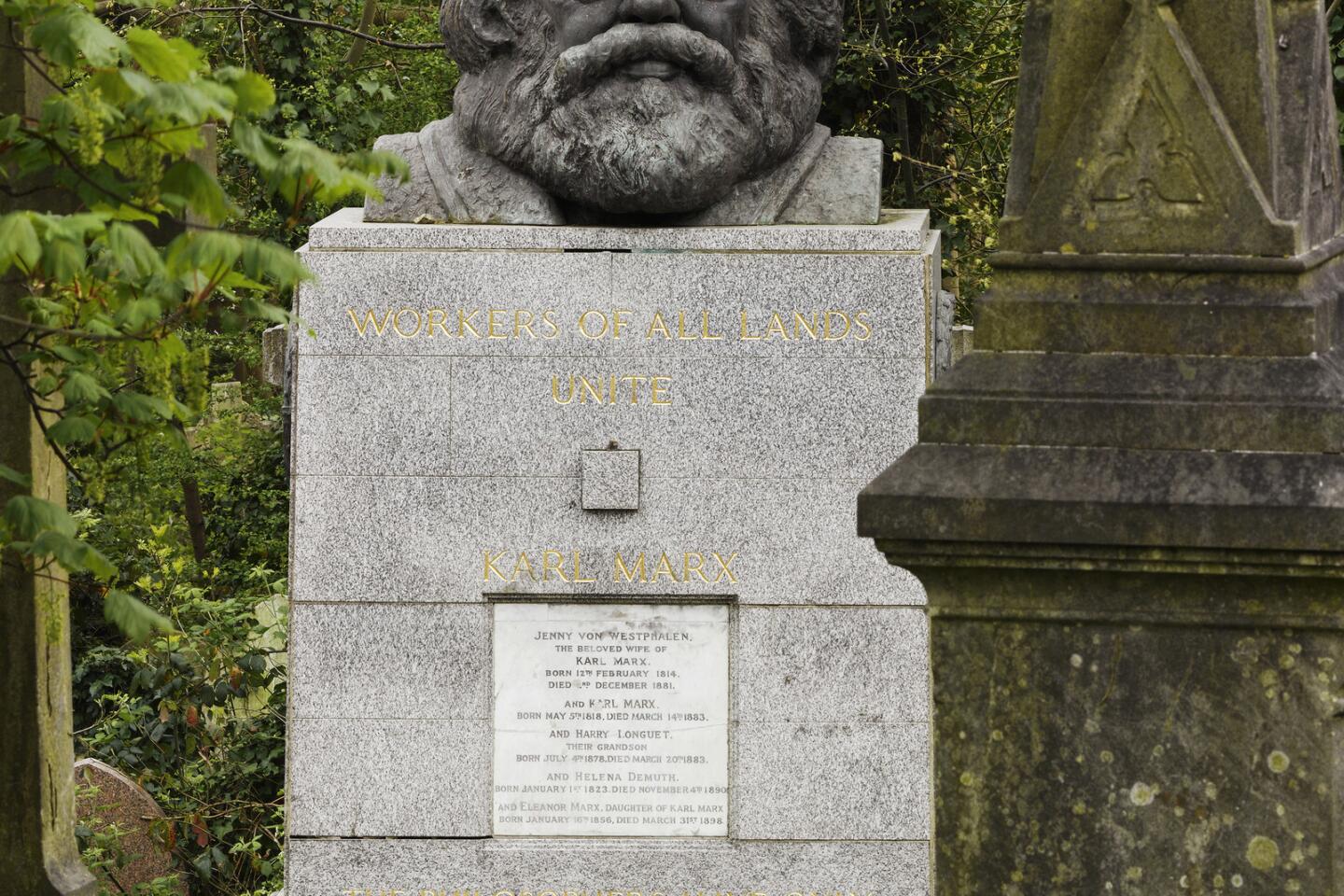

It also happened to have been my playground as a child, when I lived nearby. In early summer, we children explored through clouds of white Queen Anne’s lace; in the fall, we shared luscious blackberries with the squirrels and foxes; in the winter, we played in the snow. We weren’t interested in the cemetery’s most famous occupant, Karl Marx. I remember I didn’t like his enormous black head sitting neckless on a pillar. Where was his body?

Highgate became overgrown and vandalized (not by us) and was finally abandoned in 1975. A few years later, Friends of Highgate Cemetery took it over. Enthusiasts weeded and cleared the ivy from the graves, cut down invasive trees and planted bulbs and wild flowers. For a while, I volunteered as a guide. I showed visitors the tomb of boxer Thomas Sayers with his mastiff, confusingly named Lion, while a sleeping stone lion called Nero guards the grave of George Wombwell, a menagerie owner.

A crude horse marks John Atcheler’s grave, appropriate for Queen Victoria’s horse slaughterer. Angels are everywhere, morphing with Victorian prettiness into something more like fairies: One has even fallen asleep on a grave.

Highgate architect Stephen Geary created an air of mystery with his curving paths reminiscent of those in Père Lachaise. Geary’s Egyptian Avenue is a street where the dead live in little houses, each with an iron door stamped with an inverted torch (light extinguished).

Highgate’s other great feature is the catacombs, an underground gallery with a terrace on top where Victorians paraded, admiring the view across London to the South Downs. Today, it is no longer safe to walk there, and the view has disappeared behind a screen of tall trees. Unplanned but allowed to take root, the trees have become the chief beauty of the place.

There is never a bad time to go to Highgate, but my favorite is the early spring, when the trees are bare and snowdrops are everywhere.

If you get bored, there are four additional cemeteries in the Magnificent Seven, as well as plenty of other graveyard mysteries in London that I’ve yet to explore. For instance, where can you find the remains of Sigmund Freud and his wife, Martha? Hint: They’re not in a cemetery.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.