Seeing Charleston, S.C., in a new light

CHARLESTON, S.C. — When the email proposing a business meeting in Charleston popped up, it took all of three seconds to say yes. I’d never been to South Carolina, but I’ve read glowing dispatches from friends and colleagues for years. Southern hospitality is not a myth, they insisted, as they extolled the beauty of the area and its vigorous dining and bar scene.

When I started to research this coastal city, it was its Civil War-era attractions that proved most compelling. After all, the war “started” here when Confederate forces forced Union troops from Ft. Sumter in April 1861. And the city has a storied 19th century history, with a long list of monuments, mansions, plantations and museums that support it. So I scheduled some extra time during my February trip and designed an itinerary that would take me to four or five attractions each day.

The tour of elegant homes and cobblestone streets, period antiques and marble shrines was an excursion through the histories of prominent families and institutions. The guides were gracious; the structures, beautifully maintained. But everything seemed so pristine, so contained. Where were the stories and the artifacts that acknowledge the inhumanity of slavery or the social failures of Reconstruction?

I visited cemeteries, plantations and city mansions, museums and national parks (see story on two Civil War attractions), and I discovered that those narratives exist — at some of the same places where antebellum silver gleams. You may have to read beyond the first few lines of description in the guidebooks to find experiences that acknowledge slavery and its legacy, but without them, the city’s story is unknowable.

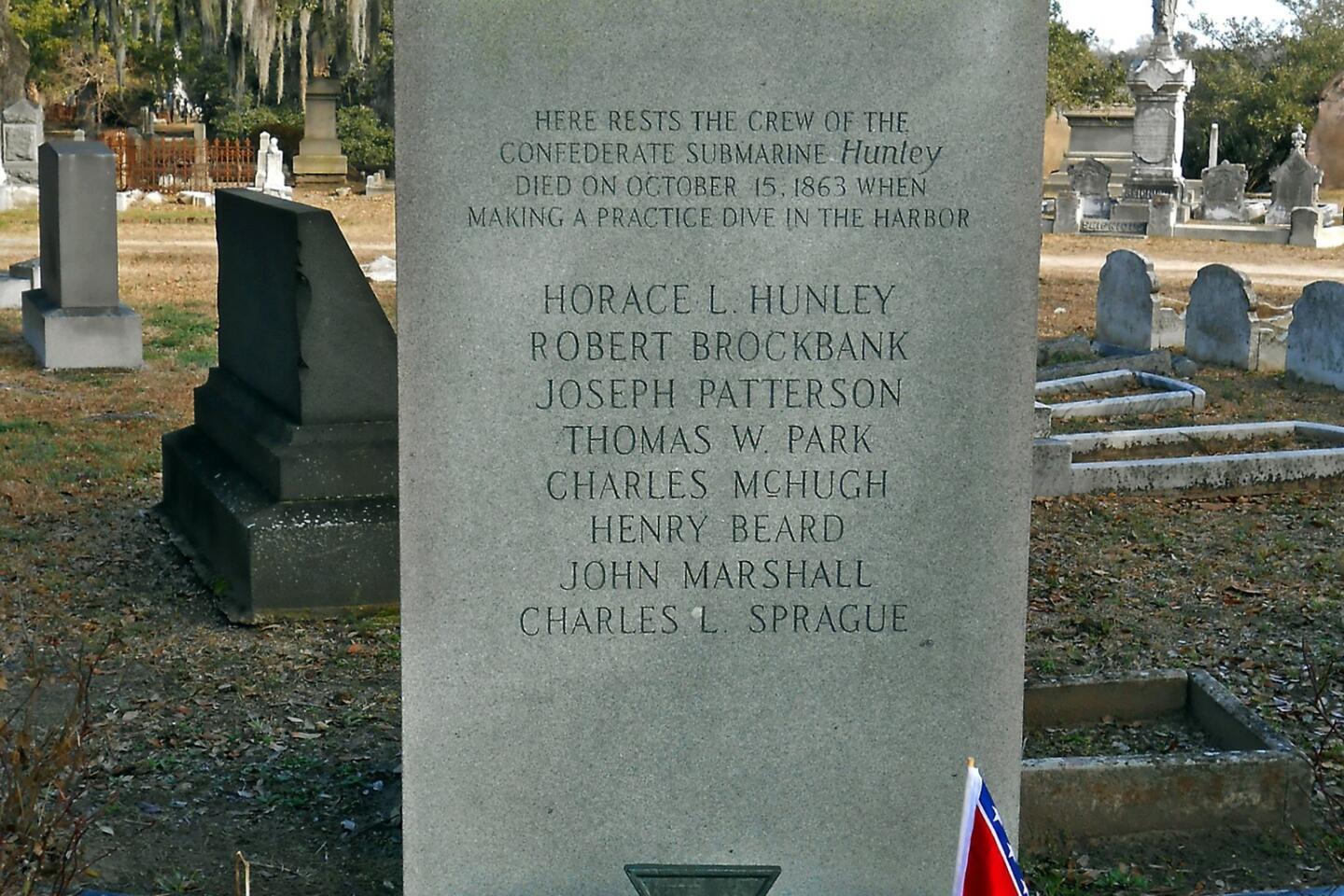

Confederate burial ground

I started my journey where history, tradition, movie-worthy scenery and cataclysm converge: Magnolia Cemetery.

The cemetery, which was founded in 1849 and is on the National Register of Historic Places, was a 15-minute drive from my hotel in downtown Charleston. Starting at 9 a.m., I walked the grounds for an hour without seeing another visitor. I did encounter long-legged water birds, trees draped with Spanish moss, pedestrian bridges over quiet ponds and family plots with 19th century tombstones that recall the sad mysteries of multiple infant deaths. Even so, “tranquillity” was the word that came to mind.

Or was the word until I walked to a memorial surrounded by several graves of men who died during the war. Many of the small tombstones had been decorated with small Confederate flags.

“It has the largest concentrated Confederate burial ground in the area, but I don’t consider it a Confederate cemetery because 33,000 people are buried here over 160-plus years,” Beverly Donald, Magnolia Cemetery’s superintendent, said in an interview with Patrick Harwood, a communication professor at the College of Charleston. (Harwood posted the interview on his CofCMultimediareporting blog.) But more than 2,000 Civil War veterans are buried at Magnolia, and those rebel flags invite contemplation of their history and their symbolism.

After my time in the cemetery, I drove about 30 minutes to Ashley River Road, a thoroughfare named after the river that proved crucial to the wealthy men who built their plantations nearby. That led me to Drayton Hall, an 18th century plantation home noted for its Georgian-Palladian architecture.

Guidebooks usually make the distinction that Drayton, a National Historic Landmark, has been preserved, not restored. Because of that, the rooms were devoid of furniture and accouterments; some of the walls were most recently repainted in the 19th century. The emptiness was startling at first, but it certainly focused my attention on Drayton’s authenticity.

Our tour guide was well-versed on the seven generations of Draytons associated with the plantation. John Drayton, who built Drayton Hall, was the third son of Thomas and Ann Drayton, who built the nearby Magnolia Plantation. She also spoke about the lives of seven generations of African Americans connected to Drayton Hall, even though little of their physical world remains. (The impressive website https://www.draytonhall.org includes a timeline of the Drayton family and the African Americans who served them, many of them as slaves, others, later, as domestic employees.)

I found the most moving acknowledgment of slavery on the plantation in a quiet wooded area — an African American cemetery that, the website says, is “the final resting place of at least 40 individuals, enslaved and free.” A wrought iron arch with the words “Leave ‘Em Rest” stands at the entrance, but there are few markers otherwise.

Just up the road, Magnolia Plantation, which is often compared with Drayton, tells a different story.

The original plantation home at Magnolia burned in the 1790s. A second home was burned in 1865; official literature points a finger at Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s “renegade Union troops.” After the Civil War, the Rev. John Grimké Drayton dismantled a nearby summer home and had it reconstructed on the footprint of the burned-out plantation house and agreed to open the extensive gardens to paying visitors.

The home was expanded over the decades, and today the public can tour 10 rooms, furnished with family artifacts, quilts and antiques. If Drayton Hall is stately and austere, Magnolia is approachable and rambling, a larger version of your great-grandparent’s farm home that your relatives tried to update in the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s.

Historically minded visitors sometimes grumble about Magnolia’s petting zoo (not exactly part of the original setup), and some tour guides who don’t necessarily emphasize (or even mention) the slaves who kept the place and its family together. (My guide briefly referenced the slave population.) But five years ago, Magnolia instigated a series of tours that focus on a group of restored cabins, most built to house slaves and domestic workers, that acknowledge the different eras of the occupants, starting with 1850 and running through 1969.

Well-earned reputation

I was eager to sample some of the Southern fare that has prompted media coverage and visitor conversation. Husk, which is in an elegant late-19th century house in historic downtown Charleston, boasts Sean Brock, a James Beard Award-winning chef who helped launch a much-acclaimed locavore movement.

I ordered glazed pig ear lettuce wraps with kimchi-marinated cucumbers and red peppers and cilantro; arugula salad with shaved apple and honey-glazed beets, Asher blue cheese, oat granola and bourbon vinaigrette; and a bibb lettuce and tomato salad with cornmeal fried Carolina shrimp, boiled egg, shaved onion and pancetta vinaigrette. The verdict? Husk’s sterling reputation is well deserved.

The next night, I dined with colleagues at FIG (Food Is Good). The Capers Blades oysters and the sautéed golden tilefish with Carolina gold rice grits, broccoli and benne seed were remarkable. The vibe was lively with a promise of Friday-night-giddy later in the evening. When we left, no one wanted the party to stop.

And it didn’t. We just continued to indulge across the street at Charleston Place, the hotel where we’d reserved rooms and meeting space. Besides two restaurants, its bar, the Thoroughbred Club, serves appetizers and desserts. The bar crowd was so well dressed and playful that it almost seemed as though it had been stocked with extras.

Everything appeared to happen effortlessly at the hotel. The men and women behind the registration and bell desks had a quiet charm; the uber-chipper among them must have been retrained or repatriated. The concierges, the valets, the chamber maids — all congenial. Room service was swift. All the better to race through breakfast and hit the streets.

One afternoon I visited two institutions that surely must exist at opposite ends of some sort of cosmic spectrum: the Old Slave Mart Museum and the Confederate Museum, a 10-minute walk apart. In 1856, Charleston passed a ban on the public sale of enslaved African Americans; the transactions then moved indoors to several sales rooms, or marts. What is now known as the Old Slave Mart Museum is “possibly the only known building used as an … auction gallery in South Carolina still in existence,” according to https://www.charleston-sc.gov.

There is almost no memorabilia in the facility, which opened in 2007 and is owned by the city of Charleston. Instead the small two-story structure is full of text-heavy wall panels devoted to various chapters in the horrific saga of domestic slavery. The juxtaposition of the exhibits in the space and its past unsettled me.

By contrast, the Confederate Museum is chock-full of memorabilia: a lock of Robert E. Lee’s hair (attached to a signed, framed letter), baby clothes, furniture, oil portraits, buttons, rosters of Confederate soldiers, Confederate money, Confederate flags and snippets of flags, baskets, buttons, rifles, bayonets, swords and a greenish-gray frock coat worn by Samuel Tupper Hyde, who was 17 years, 8 months old when he died in a battle on Morris Island in Charleston Harbor on July 18, 1863.

It’s a strange, cluttered place — a perverse curiosity shop — run by the Daughters of the Confederacy and crammed to the gills (curator, what curator?). And here’s the strangest juxtaposition of all: The collection is housed in an 1841 Greek Revival building that sits atop the Charleston City Market, where the vendors include African American men and women who sell one of the most iconic souvenirs of the Charleston area: sweet grass baskets, a craft introduced to the area in the 17th century by enslaved people from West Africa.

My itinerary also included a self-guided walk past many of the city’s well-preserved homes. There, as at many other of Charleston’s attractions, the back story was just as fascinating — or troubling — as the official literature. The Aiken-Rhett House, for example, an impressive structure open for touring, was once owned by William Aiken Jr., a rice planter and governor of South Carolina. He was also one of the largest slaveholders in South Carolina, and it is that tangled history that remains with me, after memories of fine food and historic preservation have faded.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.