Peru comes alive with irresistible rhythms

Lima, Peru

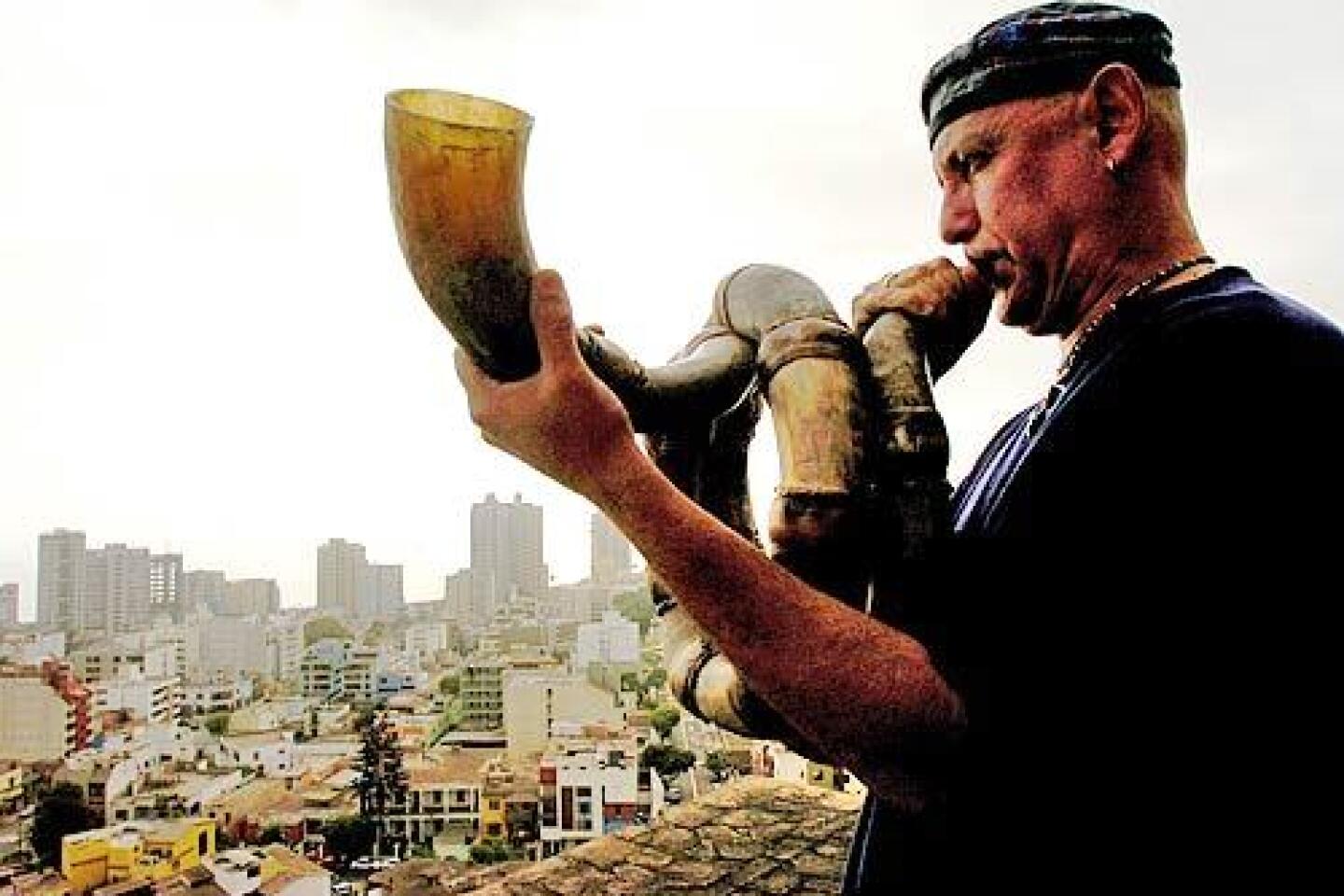

The penthouse recording studio of musician Manuel Miranda enjoys a panoramic view of this ancient and strangely compelling city. When he turns down the lights and turns up his bewitching brew of ancestral Andean melodies, jazzy rhythms and soaring synthesizers, he creates a mystical ambience that converts his 17th-story condo into an Inca temple.

Miranda, a guru-like figure who sports earrings and a beaded necklace, plays a battery of historic instruments over the recorded tracks from his upcoming album, “Brujos Voladores” (Flying Wizards). He rattles shells and blows on flutes made of wood, stone and pelican bone, evoking the mysteries of the cosmos, the primitive search for water, the origin of civilization.

In Lima, experimental artists like Miranda are concocting new ways of salvaging Peru’s rich musical traditions by updating them with contemporary elements of jazz, rock, salsa, reggae and electronica. During a visit last fall, I was thrilled to discover these artistic efforts to revive Peruvian music, one of the most powerful yet underappreciated cultural traditions in the Western Hemisphere.

Though less well-known than the Argentine tango, the Mexican mariachi or the Cuban son, Peruvian musical traditions are no less rich. Ardent proponents are working to ensure the survival of the country’s distinctive sound, worried it could be lost as youth turn to foreign pop fads.

Lima, like its music, suffers a crisis of self-esteem. This ugly-duckling city of 8 million may not have the breathtaking grandeur of Mexico City, the cosmopolitan elegance of Buenos Aires or the graceful beauty of Havana, but it has that intangible quality called soul, reflected in its friendly people and their passionate songs, and that makes it equally memorable.

Skies are overcast in Lima almost year round and many tourists consider it an avoidable way station on their treks to Cuzco and Machu Picchu, centers of Inca civilization about 750 miles southeast. But when it comes to music, Lima is the hub.

Americans tend to associate Peruvian music with the mournful, folkloric flute sounds of the Andes, popularized by Simon and Garfunkel’s “El Condor Pasa,” the 1970 hit with Urubamba, a group that wasn’t even Peruvian. More recently, Peru’s best-known musical export has been singer Susana Baca, whose sophisticated style purists still consider too refined. Yet, Peruvian music is as diverse as the country’s dramatic geography and multiracial makeup.

Lima and its coastal environs are best known for msica criolla, a blend of Spanish, Indian and African elements as tasty as the new fusion cuisine that’s putting this city on the culinary map. The styles are as varied as the graceful marinera, danced with twirling handkerchiefs, and the romantic vals peruano, an earthy, urban waltz danced with a shuffle to the feet and sway to the hips.

Running through it all is the rhythmic legacy of Peru’s black musicians, descendants of slaves who created their own distinctive song forms and dances, such as the mournful lando, the provocative festejo and the rowdy alcatraz.My relationship with Lima and its music is personal. My first wife, whom I met when we were students at UC Berkeley in the ‘70s, was born and raised in Lima. I fell in love with the music, the sweet melodies, the poetic lyrics, the irresistible rhythms. But on this trip, I wasn’t sure what I would find. By the 1980s, all of my ex-wife’s family had immigrated to California, joining the sizable expatriate community. The last I knew of Lima was that people wanted desperately to leave, to escape the city’s perfect storm of urban woes — terrorism, poverty, crowding, crime, corruption and crumbling infrastructure.Today, Lima is enjoying a civic and cultural resurgence. Night life has returned to the once dangerous historic downtown, due north of Miraflores, where authorities have illuminated major colonial buildings as part of a full-scale restoration effort. New restaurants, good hotels, fine art galleries and trendy nightspots abound, luring tourists back.

Musical fusion

Almost every traveler arrives in Lima through Callao, the gritty port adjacent to Jorge Chavez International Airport. Once the shipping point for Inca gold headed to Spain, the district is now known as Lima’s hotbed for salsa music. From there, most visitors head directly to the upscale districts of Miraflores or San Isidro, a straight shot along the coastal road that lines Lima’s brownish bay from La Punta to Chorrillos.

Aside from being safe for shopping and strolling, Miraflores is a good base from which to explore Lima’s music.

The fusionists, who perform in public only occasionally, have found a welcome venue at El Cocodrilo Verde (226 Francisco de Paula Camino), a nightclub that features a variety of live music. Late last year, the club hosted a series of concerts dubbed “Etno Fussion,” featuring top names in the field — from pioneer Miki Gonzalez to the newest multinational ensemble Novalima, which creates a powerful fusion of electronica with intoxicating Afro-Peruvian percussion and vocals.

The nearby Jazz Zone (656 La Paz), a hip and hopping upstairs club, provides a showcase for the city’s eclectic jazz scene, including the ubiquitous saxophonist Jean Pierre Magnet, who also experiments with fusions of jazz and msica criolla, working up a trance-like intensity the night I saw him perform.

For traditional Peruvian music, Lima’s peas are the place to go.

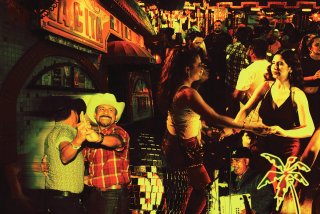

Historically, peas were social clubs that sponsored gatherings of music-minded friends and neighbors, sometimes in private homes along Lima’s colonial alleyways. Nowadays, many peas have become touristy. To attract a younger audience, some have started to feature rock or reggaeton.

Peas can be found throughout the city, forming a network that gives singers a chance to run the circuit, performing short sets from place to place in a single night. Few tourists venture to the more isolated venues, such as El Plebeyo (named after a famous song about a romance doomed by class distinctions), in a vaguely menacing area near downtown called Brea.

Regardless of location, peas are normally well-illuminated and well-guarded. But some U.S. tourists may feel trepidation about venturing out, even for the matinee at Las Brisas del Titicaca, a huge dancehall-style venue near downtown. At 40 soles (about $12) for admission, the spectacular folkloric shows at Brisas are well worth the visit, offering a thrilling survey of Peru’s regional dances, as varied as Mexico’s Ballet Folklrico.

Though too large and structured to be considered a pea, Brisas definitely retains that warm family atmosphere. Tables surrounding the ample dance floor are filled with everyday Limeos marking special occasions — a military colonel out on his birthday, accountants proud of passing their certification exams, hospital workers marking the Day of the Anesthesiologist. They all stand and raise a toast when they’re introduced by the emcee, then get up to dance cumbia and salsa to a live band during breaks in the floor shows.

For those who insist on sticking to well-worn tourist trails, several of the best-known peas are concentrated in the popular Barranco neighborhood, a lively bohemian district a quick cab ride south of Miraflores. The artsy seaside enclave features quaint cafes such as La Posada del Angel (at three locations) and trendy nightclubs such as La Noche (307 Avenida Bolognesi), which features rock and jazz.

Barranco is home to artists and writers, most notably novelist Mario Vargas Llosa, who has recently staged a spoken-word show called “La Verdad de las Mentiras” (The Truth About Lies), backed by the solo flute of Miranda, the mystical fusionist of Miraflores. The community is also home base for Novalima, the powerful Afro-Peruvian fusion group whose latest album, “Afro,” was released last year in the United States by the L.A.-based Quongo label. Barranco is a great place to stroll, night or day, with musicians and food booths filling the plaza in front of its city hall.

The Barranco barrio is also associated with a name considered royalty in Peruvian pop music circles, Chabuca Granda, one of the country’s premier songwriters. Granda personifies Lima’s Creole mix of elegance and earthiness in songs such as “La Flor de la Canela” (Cinnamon Flower) and “El Puente de Los Suspiros,” the latter named for Barranco’s landmark Bridge of Sighs, a favorite lovers’ hideaway since the 1800s.

It’s easy to find peas in Barranco because many are listed in tour guides. The challenge is finding one that retains that authentic pea spirit.

I was lucky to be pointed in the right direction by an expert in the subject, percussionist Gigio Parodi, who plays cajn (the genre’s iconic box drum) with Peru’s top criollo and jazz musicians, including singer Eva Aylln and Los Hijos del Sol, featuring drummer Alex Acua, L.A.’s own Peruvian fusionist. The affable Parodi, who seems to be friends with all of Lima, took me on a cruise of the usual peas one night. The most memorable, La Pea de Don Porfirio, was the easiest to overlook, tucked away just off the Avenida Bolognesi at 115 Manuel Segura, with only a modest sign outside. Inside, rows of wooden tables are arranged in long rows with people sitting on benches and dancing in the cramped aisles.

This is the real thing, Parodi says, a pea patronized by musicians who arrive after making the rounds at more commercialized venues. Parodi also claims they come for the finger-licking lomo saltado, a beef and potato dish, which he dubs “the best in town.”

Don Porfirio offers shows only on Fridays from 10 p.m. to 8 a.m., with music workshops here the rest of the week. The sound is strictly acoustic, notes Parodi, “just like at home where there is no sound equipment.”

Our tour ended just before dawn at Sachn, a pea on Avenida del Ejrcito in Miraflores that has seen better days. So has my favorite singer, Zambo Cavero, who is now too obese to bend over his cajn and seems to be just going through the motions on stage. The spectacle took on an air of decadence when celebrity guest Laura Bozo, the controversial talk-show host who is considered Peru’s Jerry Springer, did a lap dance on the singer’s enormous belly.

There’s something both sad and inspiring about Lima. It looks as if it has been through a lot. Yet it’s making a valiant effort to restore its dignity, recover its vitality and preserve its traditions.

Nowhere is the challenge of this effort more glaring than in the historic center, the heart of this once glorious capital of the old Spanish empire. Strolling the streets, a visitor comes upon the once stately Teatro Municipal, still shuttered after being gutted by fire eight years ago. And at the dark and spooky Gran Hotel Bolivar, once frequented by the likes of Ernest Hemingway and Ava Gardner, you find a KFC where the old Bar Ingls used to be, its fast-food sign facing the historic Plaza San Martn.

But nearby at the Plaza Mayor, you also find a stylish new restaurant named T’anta Lima. And printed on the cover of its burgundy menu is a mission statement that captures the creative spirit driving Lima’s recovery: “A great city first of all values its traditions, restores its monuments, gives life to its rivers and beaches, waters its gardens and makes of art its flag, inspiring its citizens to take part in a dream, one in which the city by salvaging its soul finally finds modernity.”

That calls for a criollo shout-out: Qu Viva El Peru!

agustin.gurza@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.