‘Rock & Roll Billboards of the Sunset Strip’ shows grand-scale visions

I was 13 years old when my brother placed a round, grooved disc of vinyl on the record player, dropped the needle and introduced me to the Doors, an L.A.-born band whose mystical-sounding lyrics, mind-bending imagery and unique organ riffs were unlike anything I’d ever heard. I didn’t know it then, but the music I was hearing for the first time would change me, following me across two coasts and four decades, forming the foundation of my life’s soundtrack. Jim Morrison’s voice transported me from the hills of rural Vermont to the blood-filled streets of New Haven, Conn., sent me wandering in and out of whiskey bars and introduced me to the exotic species known as an L.A. woman long before I would see one up close.

Music has a profound power to shape the world around us. What we listen to can influence our friendships, what we wear, where we dine, even where we lay our heads at night. But to affect us, the music first must reach us, traversing a crucial “last mile” between creator and consumer. Today that distance is just the few inches between ear and iPhone. But an upcoming exhibition at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles shows how, once upon a time, billboards along a fabled strip of Southern California real estate were key in bringing rock music to the masses.

“Rock & Roll Billboards of the Sunset Strip,” which opens March 24 and is scheduled to run through Aug. 16, features photographs by Robert Landau of billboards along that heavily traveled route. The exhibition makes the case that they were integral to the success of the music industry for more than a decade and a half, starting in the late ‘60s.

According to Landau, the first rock ‘n’ roll billboard was the one Elektra Records head Jac Holzman erected in 1967 to promote the Doors’ debut album, hoping to pique the interest of the radio DJs who drove up and down Sunset to work. That touched off a rock-promotion land grab.

Although he isn’t quite as precise about pegging the end of the era, Landau is more than happy to finger the culprit. “The era lasted about fifteen years, just barely into the Eighties,” he writes in the 2012 book “Rock ‘N’ Roll Billboards of the Sunset Strip” (Angel City Press), which prompted the exhibition. “That was the time MTV and VH1 diverted music-industry advertising dollars from hand-painted billboards to sensually choreographed music videos.”

This arc of influence is reflected in the images that make up the exhibition: a series of 24-by-30-inch photos (and a handful of 24-by-36-inch images) of billboards graced by David Bowie, Marvin Gaye, Donna Summer, the Who, Pink Floyd and the Beatles. Far from billboard size, they’re still large enough to capture some of the considerable artistry of the hand-painted surfaces.

“We wanted to do something that gave people the scale of the billboard art and the craft that goes into making it,” said Skirball assistant curator Erin M. Curtis. “So we’re having a muralist named Enrique Vidal come in and paint a billboard-size 12-foot-by-22-foot mural in the gallery that depicts a portion of Jerry Garcia’s guitar, Wolf.” Curtis explained that Vidal, who had been a professional billboard painter for 20 years, would paint a very small portion of the guitar — which really is named Wolf — very large “to sort of give a feel for the impact and awe-inspiring scale of billboard art. It’s tough to convey how much work [went] into creating these billboards that looked like photographs, especially when we think about what’s possible now with digital printing.”

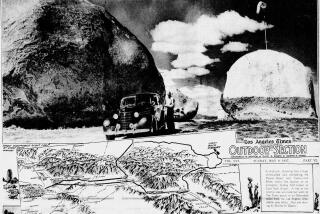

Landau’s photos don’t just capture the billboards in a way that makes one nostalgic for hand-painted plywood. Many of them include snippets of the world in the corners of the frames, capturing the cars, the houses and the long-gone businesses, the hairstyles and outfits of passersby.

Because Landau leaves us at the doorstep of the MTV era, we couldn’t help but wonder what the modern-day version of the rock ‘n’ roll billboard might be. “The point of the billboards was [that] you’re in Los Angeles, there’s a car culture here, and they needed to bring the message of this music to where it was going to be met,” Curtis said. “That’s what YouTube is doing today, so I think that’s the closest analogue, even though it’s a very different form.”

Sure, music is more accessible than ever, and maybe that’s a good thing for the music business. But the mythology of music suffers when all the world’s past and future rock gods can be clutched in a single hand. What Landau’s photographs do is remind us of the time when the Sunset Strip was the rock gods’ Olympus, the billboards were their thrones and the thunderbolts they hurled could be felt clear across the country — even in the hills of rural Vermont.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.