China offers concessions on trade as its economy shows signs of decline

China appears to be giving ground on U.S. demands to clean up its act on trade and foreign investment ahead of a new round of trade talks between the two sides next month.

In a draft law on foreign investment released earlier this week, Beijing proposed greater intellectual property protection for overseas firms operating in China and to refrain from interfering in the operation of foreign businesses. The law, published by the top legislature, could help address long-standing U.S. concerns that China is systematically stealing American companies’ technological know-how.

For the record:

5:20 p.m. Dec. 28, 2018An earlier version of this article referred to Keyu Jin as “he.” Jin is a woman.

The move came amid continued signs that China’s economy is losing steam. The government reported that industrial output grew in November at the slowest pace in a decade, in good part because of the trade war with the United States and a drop in domestic auto production.

“The economy is slowing down for sure,” said Larry Hu, head of Greater China Economics at Macquarie Group. “It has already slowed over the past four quarters, and will slow for another four quarters.”

The draft law will remain open for public comment until mid-February, allowing scope for adjustments after face-to-face talks between the two sides in Beijing. China’s Commerce Ministry spokesman Gao Feng confirmed Thursday that a U.S. trade delegation will travel to China for negotiations in January, following what he called “intensive” phone communication over the holiday period.

“China has stepped up in terms of key intellectual property enforcement institutions, and in the courts, a lot of cases are Chinese versus Chinese — that’s a good sign,” said Keyu Jin, an associate professor of economics at the London School of Economics. “Getting it right will take some time — don’t forget that 30 years ago people [in China] did not know what a lawyer was.”

However, it is unclear whether the law will be enough to placate U.S. concerns. This spring, Dennis Shea, the deputy U.S. trade representative who serves as ambassador to the World Trade Organization, called forced technology transfer an “unwritten rule” for companies trying to do business in China.

China’s proposed foreign investment law is intended to ensure equal treatment for foreigners in areas such as government procurement, and provide protections so they would not be pressured to hand over trade secrets to have access to the Chinese market.

“These positive steps are still not enough, due to pervasive national and local incentives in China … to acquire new technologies and the difficulties in tracking forced technology transfer,” said Mark A. Cohen, former senior intellectual property attache at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing, writing in his China IPR blog.

In addition to technology transfer issues, the Chinese measure would allow overseas-listed firms to raise funds by issuing stocks and bonds, and lifts capital constraints on sending income abroad.

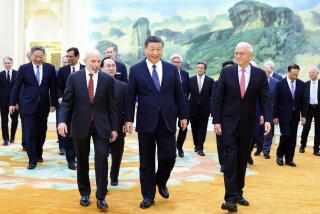

Some analysts suggest that concessions on foreign investment might form part of a package that could ease trade tensions that have been escalating all year. That would also allow U.S. trade negotiators to demonstrate success in the talks in Beijing next month, following a meeting between President Trump and his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, at the G-20 summit in Buenos Aires earlier this month that led to the agreement on a 90-day cease-fire in tariffs.

“China is going to say that a good portion of the items demanded by the U.S. will most likely be met, and the other items there will be an open conversation,” Jin said, although she added that any agreement will probably be a “nominal” or short-term deal given the “deeper, more intractable issues between the two sides.”

U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, who is leading the China talks for the Trump administration, has insisted that Beijing must open up its market and make structural changes that protect American intellectual property, including Chinese action on cybertheft and state-supported efforts to buy up technology. If there isn’t a deal by March, Lighthizer said, U.S. tariffs on $200 billion of Chinese imported goods would be increased to 25% from the current 10%.

China this week announced other measures that could pave the way to a deal.

On Monday, the Finance Ministry said it would cut tariffs on a provisional basis on more than 700 goods beginning Jan. 1, the third such announcement this year, offering a potential boost for U.S. exporters of cotton, pharmaceutical ingredients and other commodities.

Then, on Tuesday, authorities developed efforts to standardize market access rules for both foreign and domestic business with the publication of a “negative list” indicating areas of the economy in which investors are restricted or prohibited from taking part.

“The promulgation of the negative list nationwide means that China has set up a unified, fair and rule-based system for market access,” said Xu Shanchang, an official of the National Development and Reform Commission, China’s top state-planning agency.

Pressure is building on China’s policymakers amid evidence the domestic economy is hitting headwinds as the year draws to an end.

The National Statistics Bureau reported Thursday that industrial profits declined 1.8% in November from the year before, the first contraction since the end of 2015, tracking weak retail sales and slowing industrial production. China’s Shanghai Composite Index is the worst performing major market index this year, down about 25%.

American negotiators also have incentive to seek a thaw in trade relations: U.S. benchmark stock indexes have fallen sharply since October, amid rising interest rates and expectations of more moderate economic expansion next year as the effects of tax cuts wane and global growth softens.

“It’s clear that the world economy is starting to slow, and it’s not just China that will be weakened by this trade war,” said Rafiq Dossani, a senior economist with Rand Corp. who follows the Asian economy.

Times staff writer Don Lee in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.