A grim pattern in European attacks: Missed chances to pinpoint terrorism suspects beforehand

In ancient capitals and bustling provincial cities across Europe, whenever the first sketchy reports begin surfacing of a terror attack — a truck strike, a stabbing rampage, a bombing — the investigators who spend their days and nights sifting through tens of thousands of potential security threats feel a sense of dread beyond their horror over the immediate event.

Will a perpetrator turn out to be someone well known to them? Someone whose extremist views or suspicious travels or damning personal associations had been documented but fell short of grounds for arrest or other restrictions?

Could the latest atrocity, they ask themselves, have been averted?

That agonizing question is being asked in London, where a vehicle-and-knife attack June 3 in the heart of the capital killed eight people and cast a shadow on a consequential British election.

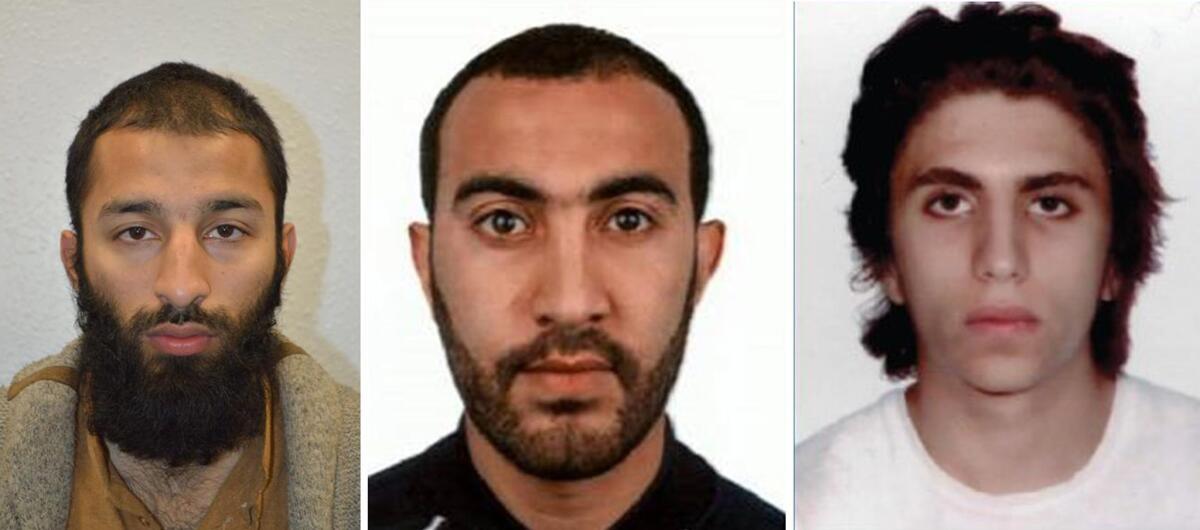

In the London Bridge attacks, authorities had previously been told that two of the three assailants had shown extremist tendencies — echoing a pattern in other terrorist strikes.

But tracking terrorism suspects and heading off attacks — even when someone has come under suspicion — has become increasingly difficult.

European nations have built massive watch lists of potential terrorists. But the lists are so extensive that it is often unclear who poses the most serious threats and thus merits close surveillance, which is both expensive and labor-intensive.

That is especially true because more and more terrorists are acting alone or in small groups, limiting opportunities for authorities to intercept communications, and are using low-tech methods that allow them to get close to their targets without attracting attention.

Further complicating counter-terrorism efforts are concerns about religious and civil liberties, which make it hard in a Western democracy to act against potential terrorists without evidence proving a crime or specific plans to commit one.

“The fact is, the threat remains mostly unpredictable,” said Jean-Charles Brisard, chairman of the Center for Analysis of Terrorism, a Paris-based think tank. “We are dealing with individuals who are acting in an improvised way, using very unsophisticated weapons — cars, knives, whatever.”

“They are not in communication with foreign organizations or fighters abroad,” he said. If there is such communication, he said, “they do it at the last minute … through encrypted messaging services” that are very difficult for intelligence services to penetrate and monitor.

Major attacks of recent years, including carefully choreographed large-scale strikes in Paris and Brussels, were orchestrated from outside those countries by

But several recent attacks — including last summer’s truck rampage in Nice, a knife attack in southern Germany and perhaps the June 3 assault in London — were carried out by terrorists acting alone or in small groups.

Keeping track of even a single potentially dangerous person is an extraordinary drain on time and resources, as governments throughout Europe have found.

Of the 23,000 people deemed subjects of interest by British security services, fewer than 10 are reported to be considered dangerous enough to merit formal measures such as overnight curfews, electronic monitoring and restricted Internet use.

In France, about 17,000 people are on the “Fiches S.” — for security — watch list. Given that putting a single suspect under 24-hour surveillance can involve up to 30 agents, Brisard said, “a couple hundred at best” receive that kind of attention.

Italy, which draws on monitoring methods honed in its fight against the Mafia, keeps track of about 300 potential terrorism suspects. The Italian government has recently ramped up the expulsion of foreign nationals on its watch list, 49 so far this year.

Cross-border security cooperation, long a stumbling block, remains a significant weakness, analysts say. Intelligence agencies among various countries — and even within them — do not always share what might prove to be vital information, or act appropriately when such tips are provided.

One case in point: Italian intelligence officials had informed their British counterparts that Youssef Zaghba — a 22-year-old Italian national of Moroccan descent who had moved to London and was working as a waiter — had tried to travel to Syria via Turkey, apparently to join Islamic State, the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera reported.

But neither Scotland Yard nor MI5, the main domestic intelligence services in Britain, deemed him a subject of interest, police said in a statement.

Then Zaghba turned out to be one of the attackers at London Bridge.

That underscores another big problem: Nearly every European country is coping with large numbers of their citizens who have aspirations of joining the jihadists in Syria, Iraq or Libya — or who actually made it to the battlefield and back.

As Islamic State loses territory, those followers are increasingly turning their attention to targets at home.

In Germany, the BKA — its equivalent of the FBI — says that roughly 920 citizens went to Iraq and Syria to join Islamic State, with about one-third returning home. Of the 840 French nationals thought to have headed off to join Islamic State or other jihadist groups, approximately 140 are believed to have come back to France.

Gauging threats requires the investigative calls that detectives of all stripes are used to making: when to trust your gut, how coincidences add up, when to give the benefit of the doubt, whose information to trust.

But those calls can also be influenced by larger concerns about civil liberties, social assimilation and democratic values.

In Britain, the London attack put Prime Minister

Seeking to establish her security bona fides, May has proposed what would once have been considered draconian measures, such as making it easier to deport foreign terrorism suspects and “restrict the freedom and movement” of those considered dangerous, even on the basis of evidence insufficient for a court prosecution.

“And if human rights laws stop us from doing it, we will change those laws so we can do it,” she said Tuesday.

Terrorism was also a major issue in the recent French election, in which the far-right candidate, Marine Le Pen, advocated for harsh action against anybody on the country’s watch list: expulsion for foreigners, revocation of French citizenship for dual nationals and jail for French citizens.

The new French president, Emmanuel Macron, is setting up a special counter-terrorism task force that he said will report directly to the presidential palace rather than to individual ministries, in order to reduce delays in intelligence-sharing and decision-making.

Terrorism attacks in sleepy locales in France and elsewhere across Europe have also raised concerns about whether enough resources are being devoted to the hinterlands.

One of the two radicalized teenagers who murdered a Roman Catholic priest celebrating Mass in the provincial French city of Rouen last summer had been fitted with an electronic bracelet and was only allowed out of his home at certain times of the day. He carried out the attack during his unsupervised hours.

Every attack in which authorities realize in retrospect that an individual had slipped through the cracks is a source of immense frustration. In one of many such instances, the Kouachi brothers, Said and Cherif, who carried out a deadly attack in January 2015 at the Paris offices of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, killing 12, were on France’s watch list.

The pattern surfaced again June 3. One of the slain London Bridge attackers, Khuram Butt, was also known to authorities. He had been reported to an anti-terrorism hotline in 2015 and was even featured last year in a television documentary about homegrown jihadists.

Some would-be assailants, aware they are being monitored, know that if they avoid trouble for a year or two, they are likely to be removed from the watch lists.

In Germany, Anis Amri had been on a “danger to the state” list but was removed from the list in May 2016.

Germany rejected his application for asylum and moved to deport him to his native Tunisia. But the deportation was delayed because he hadn’t yet been issued a Tunisian passport. Meanwhile, Moroccan intelligence service warnings that he dangerous went unheeded.

On Dec. 19, he plowed a stolen truck into one of Berlin’s famous Christmas markets and killed 12 people.

The documents that would have been needed to deport him came through two days later.

Kirschbaum is a special correspondent. Special correspondents Christina Boyle and Kim Willsher in London and Tom Kington in Rome contributed to this report.

ALSO

British prime minister's top aides resign after election fiasco

Was that Manila attack an act of terrorism? Trump and Philippine officials differ

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.