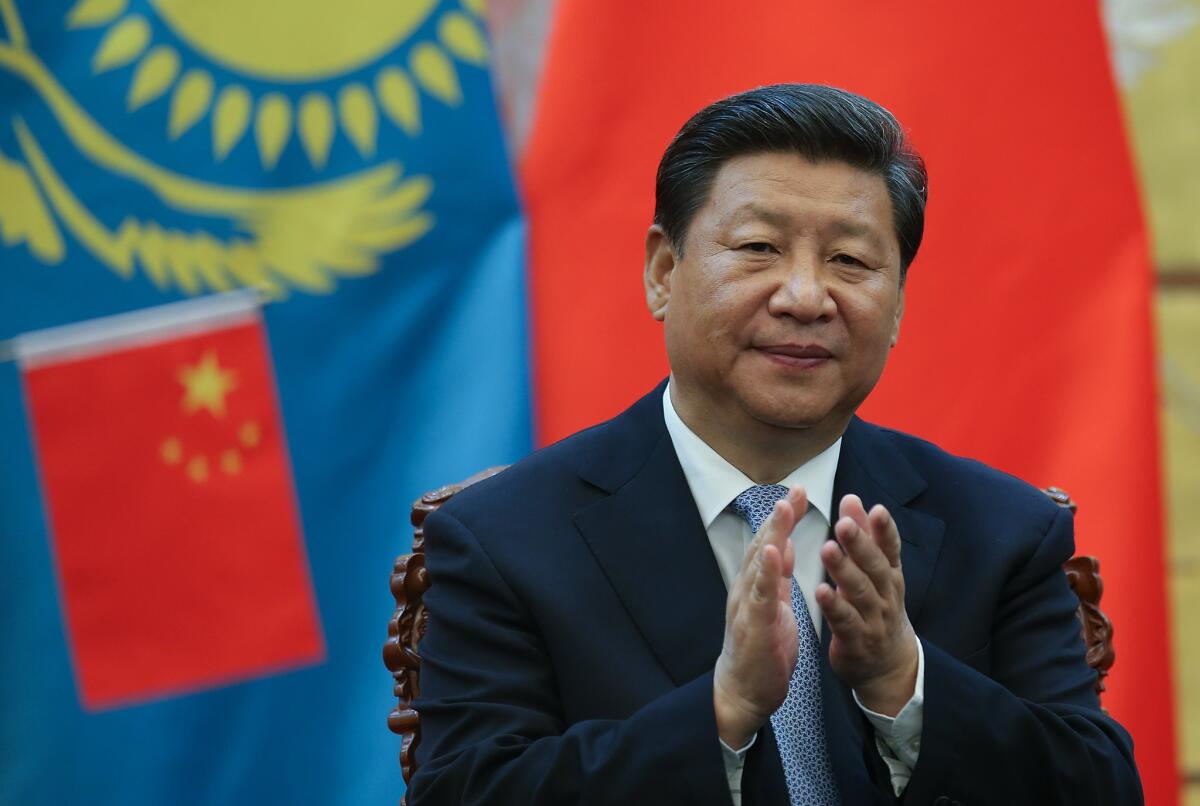

China’s Xi Jinping could use the diversion of a big military parade

China views modernization of its army as essential to achieving great power status and what President Xi Jinping calls the “Chinese Dream” of national rejuvenation.

Chinese President Xi Jinping needed a parade.

A summer of tragic accidents and terrible economic news had started to raise questions about the competence and integrity of Communist Party officials, from low-level administrators up to Xi himself. A massive military parade scheduled for Thursday provided the perfect opportunity for him to create “good news” to counter the drumbeat of negativity.

The parade, with its stream of goose-stepping troops, tanks, and ballistic missiles, wasn’t planned in response to the recent bad news. It had been in the works since the start of the year.

But the timing may be a fortuitous opportunity for Xi and Premier Li Keqiang to appear strong, in control and powerful in the eyes of the Chinese public.

“The principal audience for the parade is the Chinese people,” said Rory Medcalf, head of the national security college at Australian National University. “This will be a way for the leadership to demonstrate to the Chinese people that China will never again be coerced or bullied by external powers.”

China views modernization of its army as essential to achieving great power status and what Xi calls the “Chinese Dream” of national rejuvenation. China’s military defeats and widespread suffering at the hands of foreign military powers including England, France and Japan in the 1800s and 1900s – during the first and second Opium Wars and World War II – have long been seen as deep humiliations by many Chinese.

So parading a raft of new missiles and tanks through Beijing is an opportunity to offer optic evidence that Chinese leaders at least are taking decisive measures to ensure such national embarrassments are not repeated.

“Domestically, this is aimed at fostering a unity or togetherness of the Chinese people; it’s about realizing the ‘Chinese Dream’ and building strength together,” said Xu Guangyu, a retired Chinese military officer and consultant to the China Arms Control and Disarmament Assn.

Authorities pulled out all the stops to ensure that the parade goes according to plan – temporarily closing residential compounds, commercial areas, and transportation hubs, replacing entertainment programming with historical documentaries and anti-Japanese war dramas, and requiring people to hang large Chinese flags outside their homes and shops. They shuttered thousands of polluting factories, ensuring a day of bright blue skies.

Lao Chen, a 42-year-old shopkeeper about three miles from the parade route, said that although he was being allowed to keep his shop open during the event, restrictions on delivery services had severely depleted his inventory of snacks.

“No one wants to lose money, and this is inconvenient,” he said. “But I, together with my fellows … would like to overcome this inconvenience to support the parade. Why? Because the country has done a lot for me, and I don’t want to complain when the government needs our understanding.”

Many Chinese citizens see Xi as a forceful, charismatic leader whose campaign to root out corruption in the Communist Party is welcome and long overdue. But this summer, a string of crises -- a deadly ferry capsizing, a stock market plunge, a deadly blast at a chemical warehouse -- have started to raise questions about the Chinese government’s competence and integrity during trying times.

In early June, the nation was consumed by the story of a ferry sinking on the Yangtze River, killing 442 people – the country’s worst shipping disaster since the Communist Party came to power in 1949.

Only a month later, the tragedy was followed by a steep decline in China’s stock market. Many investors only started buying stocks this spring, after state-run media urged the masses to buy into a raging bull market, and felt burned by the sudden reversal of fortune. Authorities introduced panicky measures to stop the slide, providing large loans for buying, dramatically restricting selling, and censoring negative sentiment in the media and online.

In mid-August, the nation was rattled by a massive explosion at a chemical warehouse in the eastern port city of Tianjin. The huge blast damaged buildings miles away, left more than 150 people dead, and raised questions about why the facility was allowed to be situated so close to residential areas.

Chinese reporters and citizens asked whether the warehouse owners had used their political connections to skirt regulations, and whether officials were honest about possible hazards in the air and water.

Even the newspaper affiliated with the Communist Party’s top anti-graft organization said the incident revealed serious loopholes in Chinese law enforcement, urban planning and supervision.

“Until the moment of the explosions, the communities’ developers and residents did not know they had lived right beside a ‘volcano’,” the commentary said. “The sputtering flames engulfed not only lives and property, but also the sense of security. It again called public attentions to the question of ‘how to guarantee people’s lives and property.’”

This has all taken place against the backdrop of a slumping economy, posing a challenge to a ruling party that has staked much of its legitimacy on its ability to ensure continued prosperity and growth.

Concern is mounting that the country will not be able to meet the target for 7% economic growth this year – and that regulators are not making the right moves to put the economy and markets on better footing.

After Tianjin, China’s stock markets took another plunge, and authorities decided to slightly devalue China’s currency, the renminbi.

The respected financial magazine Caixin, in an editorial last week, criticized the authorities’ response to the gyrating markets – an unpredictable series of swings between intervention and nonintervention. “The regulator must learn the right lessons this time,” it said. “Reflecting on what it did wrong would be a start.”

Xi has made no public comment on the stock market crisis.

Tim Heath, a senior analyst at the Rand Corp. think tank, said the parade is certainly an expression of Xi’s firm policy style. Yet he added that it also reflects China’s growing status as a global power.

“As China becomes the second largest economy in the world, and one of the largest powers in the world, and it finds that its growth is leading the country more and more to bump with neighboring countries and lead into friction with the U.S., I think regardless of who the leader was in China --even if there was no Xi Jinping -- there would be a strong temptation to begin contemplation of this kind of muscle flexing,” he said. “It’s a warning to countries of the dangers of pursuing a confrontational policy.”

Follow @JulieMakLAT and @JRKaiman on Twitter for news from Asia

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.