With Mexico presidential election, another step in global populism — but this time from the left

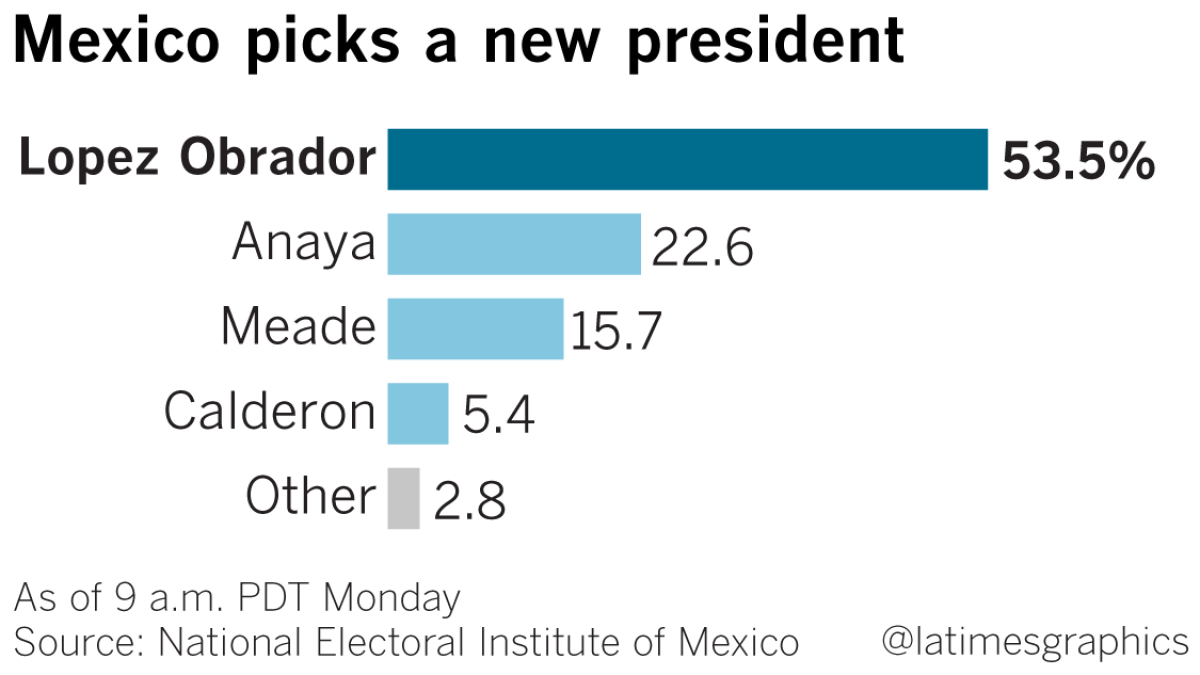

The victory of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador in Sunday’s presidential election in Mexico is yet another advance for the global march of populism, an ideology that feeds on both fear and hope.

In Mexico, however, populism comes with a twist: Lopez Obrador emerges from a leftist tradition in a sea of right-wing tendencies.

From the election in 2016 in the United States of Donald Trump to the rising leaders in Hungary, Italy and other U.S. allies, populism is posing new challenges to modern democracy.

An often anti-intellectual or xenophobic movement, populism capitalizes on existential worries among middle- and working-class populations who see their jobs being lost to technology or to lower-paid workers.

It can offer unrealistic expectations and often stokes people’s fears of immigrants and outsiders, criminals and terrorists, while railing against an ill-defined traditional elite portrayed as callously distant from the concerns of ordinary citizens.

Those touchstones are clearly part of a Trump playbook. Lopez Obrador also appeals to the common man, but his brand of populism does not employ the same level of negativity or tap into racist or nativist beliefs. It remains to be seen how it will evolve.

The underlying call to action in such a climate is to take a sledgehammer to the system, to “throw the bums out,” or, memorably, to drain the swamp.

Like Trump, Lopez Obrador benefited from a strong current of outrage where many voters felt disenfranchised, left out or overlooked.

His campaign rhetoric did not vary much from his earlier runs for president in 2006 and in 2012. He railed against Mexico’s elite and the neo-liberal economic policies embraced by Mexico’s leaders, but which many feel have left the working class behind.

What was different this time was the mood of the electorate.

“Mexicans are very angry,” said Genaro Lozano, a professor of political science and international relations at the Iberoamerican University in Mexico City.

It’s not difficult to understand why. Violence is at a modern high and fetid corruption infects seemingly every level of the established, sclerotic government. Around half of Mexico’s population lives in poverty, and the country ranks near the bottom of developed nations for social mobility, the chance to get ahead.

While Lopez Obrador’s message is unchanged, his timing is finally right.

Lozano said the vote Sunday was very much a referendum on the two political parties that have held the presidency for the last 18 years, the conservative National Action Party and the pragmatic Institutional Revolutionary Party, which before 2000 ruled without interruption for more than 70 years.

“For decades we’ve had governments that have embraced pro-Washington, neo-liberal policies,” Lozano said. “I think that many people are mad that the economic model hasn’t brought what was promised.”

Populism has been making a comeback, especially in Europe, for more than a quarter-century, and primarily on the right, said Matthew Goodwin, a political scientist at the London-based Chatham House think tank.

It led to the election in the late 1990s and again in every race since 2010 of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, on a virulently anti-immigrant platform and what he calls “illiberal democracy” that includes cracking down on a free press. It drove the so-called Brexit referendum in 2016, when British voters approved their country’s withdrawal from the European Union.

And it has bolstered the far right in France, Poland and Italy, where Europe’s first fully populist post-World War II government is taking seat.

Even in a country with as strong and established a democracy as the United States, populism fueled by economic anxiety was in part the wave on which Trump rode to victory.

“It is hard to conclude that it will disappear anytime soon,” said Goodwin, author of the forthcoming “National Populism: The Revolt against Liberal Democracy.” “We are in a new period of political volatility.”

Lopez Obrador, like Trump, is ambivalent, suspicious even, of institutions, tends to oversimplify issues, and has an ego the size of Sonora. Both tend to exaggerate their place in history and are thin-skinned and quickly rail against anyone who they perceive as having crossed them — the media, public intellectuals, business leaders, celebrities.

Beyond the left-right divide, there are important differences between the two men: Lopez Obrador is not nativist or xenophobic, and he has not proposed tariffs on goods coming into Mexico from other countries.

Like many populists, Lopez Obrador portrays himself as the representative of the people and has a tough time admitting the legitimacy of his opponents, said Carlos Bravo Regidor, a professor at the Center for Economic Research and Teaching in Mexico City.

“Lopez Obrador has been around since way before the populist wave started,” Bravo said. “But he’s coming to power as part of it.”

Lopez Obrador, widely known by his initials, AMLO, has been pounding at the same themes for at least a decade — corruption, the social roots of violence, the poor performance of the economy. But he won in part because Mexicans have embraced the anti-globalization and anti-establishment sentiments catching fire globally.

Like Trump and other populists, Lopez Obrador is making promises far beyond what can likely be accomplished.

He says he’s going to usher in a “fourth transformation” of Mexico on par with independence in 1821 and the revolution. He has vowed to improve the environment, raise wages, end violence.

Despite the populist shifts in Europe and in the United States, a reverse phenomenon has been playing out in presidential elections throughout Latin America.

In Argentina, populist Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner was replaced by a conservative, Mauricio Macri, in 2015. Conservatives have also won in recent elections in Colombia and Chile.

Comparisons to Trump, Bernie Sanders or Hugo Chavez should be made carefully, Bravo said.

Bravo said the recent leader who best compared to Lopez Obrador was Brazil’s Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva. Lopez Obrador’s time as mayor of Mexico City, where he partnered with billionaire Carlos Slim to make over the city’s historic center, shows that like Lula, “he’s a pragmatic populist.”

“If we have to go through this phase, and we have to have a populist strongman in power, AMLO is not a bad option,” Bravo said. “He might be a more benign, lighter version.”

Broadly speaking, populism in Latin America has routinely come from the left since the 1930s but is usually socially inclusive unlike the phenomenon in the U.S. and Europe, said Steven Levitsky, a Harvard University professor and co-author of the newly published “How Democracies Die.”

“Elections in a context of weak states and inequality give rise to periodic populism in Latin America,” Levitsky said. But, he cautioned, Lopez Obrador “is not Trump. His base and his project are totally different.”

Still, Mexico’s presidential election was driven by the same economic anxieties and anti-establishment sentiments that dominated the 2016 U.S. presidential race.

Voter Elena Perez Hernandez said she was fed up with the status quo.

“The corruption is horrible,” said Perez, 32, a resident of the sprawling, impoverished bedroom community of Ecatepec outside Mexico City. “The violence is getting worse. And it seems like the government protects criminal groups more than it protects us.”

Her vote? Lopez Obrador.

“We finally have hope,” she said. “He represents the people.”

For more on international affairs, follow @TracyKWilkinson on Twitter

Twitter: @katelinthicum

Wilkinson reported from Washington and Linthicum from Mexico City.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.