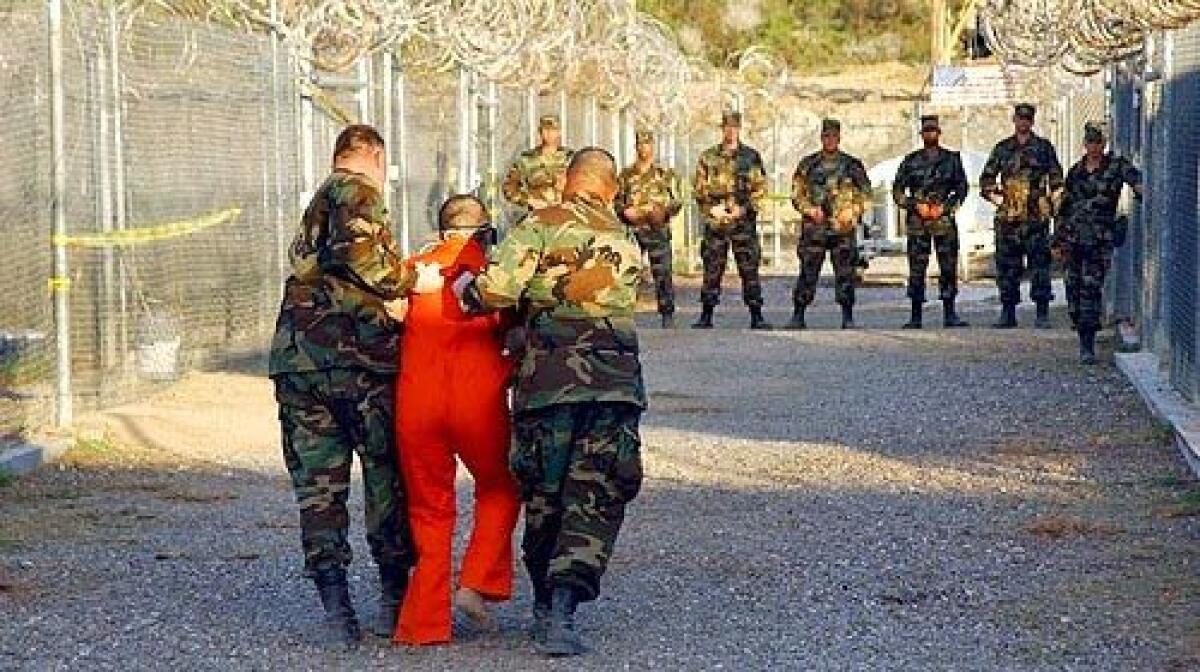

High court hears Gitmo detainee rights case

Nearly six years after foreign prisoners were first sent to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, a clearly divided Supreme Court debated Wednesday how to determine whether these men are dangerous enemy fighters or innocent bystanders caught up in the U.S. war against terrorism.

Regardless of what the court decides, the answer will not come for many months. And the likelihood is that even a ruling next spring in favor of the detained men would not necessarily result in immediate freedom for any of them. Unless the Bush administration acts to close Guantanamo, the fate of the prison and its inmates may rest with the next president.

Two options were before the high court Wednesday:

One was to treat Guantanamo as a military matter and to defer to the Pentagon to decide who will be held there and for how long.

The second option was to treat the detainees as U.S. prisoners, not enemy fighters. Under the Constitution and the traditions of American law, those who are held by the government have the right to go before a judge and plead their innocence.

The justices appeared to be split, with four leaning in favor of the Bush administration and the Pentagon, and four in favor of allowing the detainees their day in court. Justice Anthony M. Kennedy appeared to favor a middle course -- one that would require the military to give full and fair hearings to the detainees.

In several questions, Kennedy probed whether the high court could simply require the military to adopt new standards and procedures to ensure fair hearings for the detainees, such as giving them attorneys and a right to see the evidence against them.

U.S. Solicitor General Paul D. Clement, representing the Bush administration, replied that that would be one option.

But Washington attorney Seth Waxman, the Clinton-era solicitor general who represented the detainees, said: “The time for experimentation is over.” Many of the detainees, he said, have been imprisoned for years without being told of the charges against them.

Little is known about those being held at Guantanamo. Former Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld famously called them the “worst of the worst” among terrorists and enemy fighters.

Since then, hundreds of detainees have been sent home. Civil libertarians say that many of the men sent to Guantanamo were neither terrorists nor enemies of the United States.

For example, Fawzi al Odah is a Kuwaiti who was working as a teacher in Afghanistan in 2001 when the U.S. military arrived to fight the Taliban. According to his family, he was taken into custody by Pakistani border guards when he tried to escape and was turned over to U.S. authorities who were paying bounties for Arab men. He has been held at Guantanamo since early in 2002, and his case was one of two before the court Wednesday.

Waxman represented six Algerians who were arrested in Bosnia as possible terrorism suspects. They were freed by Bosnian judges who said there was no evidence against them. But U.S. agents took them into custody and sent them to Guantanamo.

In the past, Kennedy has joined the court’s liberal bloc to reject the administration’s go-it-alone approach toward Guantanamo. But he has not gone so far as to say the detainees have a right to have their individual cases heard by federal judges.

Through most of Wednesday’s argument, Kennedy sat silently while the attorneys and justices engaged in a historical dispute over whether the king of England exercised control over his subjects who were not English by birth and did not live in Britain. The U.S. Constitution’s habeas corpus protection, which gives prisoners a right to plead for their freedom in court, came from English law. So the question was whether this habeas right protects only American citizens within the United States, or instead extends to all people held by U.S. authorities in areas under U.S. control.

The Guantanamo detainees are not American citizens, but the U.S. naval base is on Cuban land that has been leased in perpetuity by the United States.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justices Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas and Samuel A. Alito Jr. appeared to agree that the prisoners at Guantanamo had no constitutional right to take their pleas to court.

“Do we have a single case in the 220 years of our country or, for that matter, in the five centuries of the English empire, in which habeas was granted to an alien?” asked Scalia.

Waxman’s argument that the habeas corpus protection did apply found favor with Justices John Paul Stevens, David H. Souter, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen G. Breyer. Twice before, they had voted in favor of rights for the detainees.

“We have passed that point, haven’t we?” Souter said pointedly to Clement. The “we” in Souter’s question presumably included Kennedy, because he agreed in 2004 that the right to habeas corpus extended to Guantanamo.

After that ruling, the Pentagon agreed to give military hearings to the detainees. These Combatant Status Review Tribunals bring the detainee before three military judges who check to see if there is some evidence that justifies holding the individual. The answer is nearly always yes. The evidence may involve nothing more than a memo describing how the individual was taken into custody.

This evidence would not likely stand up in a federal court hearing. But last year, the Republican-controlled Congress passed a law saying that no judge or justice may hear a writ of habeas corpus from an “alien” who is “detained as enemy combatant.”

While that measure seemed to close the courthouse door to the detainees, it also said the U.S. court of appeals in Washington may review the fairness of a Guantanamo tribunal’s decision.

Kennedy saw an opening there. “The court of appeals does have the right to determine whether . . . the Constitution and laws of the United States are applicable” to the military hearings at Guantanamo, he told Clement.

The justices will meet Friday behind closed doors to discuss the Guantanamo cases and to cast their votes. It is likely to take many months for a majority to write an opinion, and there will almost surely be a strong dissent, regardless of what is decided. A ruling could be announced in May or June.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.