Venezuela’s misery index gives opposition candidates a boost in Sunday’s elections

Carlos Lopez was about to undergo liver transplant surgery earlier this year when his doctors abruptly called off the procedure: Venezuela lacked the necessary postoperative drugs to keep his body from rejecting the new organ, they told him.

“I underwent eight months of pre-surgical exams for nothing,” said Lopez, a 68-year-old chemist. He also had secured a government grant to pay for the operation and an agreement from his daughter to donate a portion of her liver. “What Venezuela is going through has a human cost, not just an economic one.”

Scarcities of life-sustaining medications, ongoing hyperinflation and long lines for such basic items as eggs and shampoo have boosted Venezuelans’ misery index to the point that opposition candidates are likely to win a majority of National Assembly seats in Sunday’s elections for the first time in 15 years.

Vaccines, heart medication, chemotherapy, antibiotics and anesthetic drugs are among the commodities that are difficult to find.

“In fact, we currently are canceling all but emergency surgeries because [of] the lack of anesthesia,” said Dr. Rosario Carrillo, a doctor at a Caracas-area hospital.

Venezuelans currently wait for hours to buy many household items, if they can find them at all. Cooking oil, razors, toilet paper and car batteries are among the hardest to find. Purchasing power has been undercut by triple-digit inflation and poverty, which had declined under late President Hugo Chavez, but is now back at levels reported in 1999, the year he took office.

Inflation has reduced the real value of the minimum wage to a paltry $15 a month when applying the black market dollar exchange rate, to which prices of many items are pegged. That’s less than what workers in Cuba and Haiti are paid.

Lines of frustrated shoppers visible at stores across this capital city are symptoms of the worst economic crisis in Venezuelan history, said Jose Manuel Puente, an economist at the Institute for Advanced Administrative Studies think tank and graduate school in Caracas. Foreign reserves are drying up, the country is facing default on its foreign debt in 2016 and total economic output is set to shrink for a third straight year, he said.

“Venezuela is close to becoming a failed state,” Puente said. “Unless we generate a change in the economic model, the path soon will be irreversible.”

Disillusionment with the government is running so high that pollsters expect opposition candidates to garner a 20-percentage point win in total votes cast in balloting to elect 167 deputies. That should translate into a majority of assembly seats, with the questions being how big a majority.

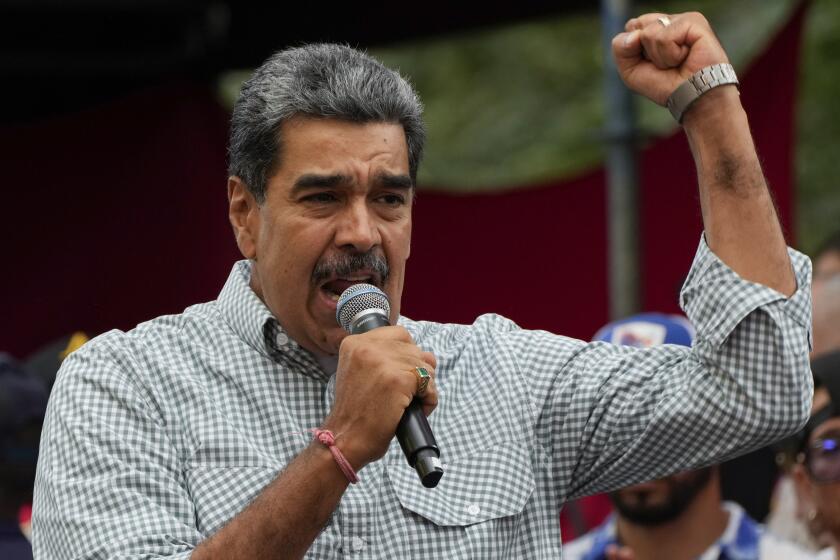

President Nicholas Maduro denied the opposition’s request for election monitors from the European Union or Organization of American States.

Citing arrests and physical harassment of opposition candidates, civil society organizations including the Foreign Policy Initiative warn that Maduro may look for a way to maintain control of the legislature after having threatened to “go to the streets” if the vote goes against him.

“If the opposition loses, no one will believe it,” said pollster and political consultant Alfredo Keller. (He declined to disclose specific polling results as Venezuelan law prohibits such disclosures in the run-up to elections.) “If that happens we could see a general strike, greater radicalization and repression.”

The government’s poor electoral prospects have much to do with Venezuelans’ rejection of Maduro, the handpicked successor of Chavez, who died in March 2013. Many analysts see the election as a plebiscite on his leadership.

“Even cha vistas want a change. They are on the edge of desperation,” said Jesus Segues, a political consultant and pollster. Of Maduro, a former bus driver, he added, “They want him to turn the bus around or hand them the keys.”

Maduro’s problems have been exacerbated by the sharp drop in the country’s oil revenue, on which it depends for more than 90% of government revenue. Because the price of oil is down by more than half since 2013, Maduro has cut back on his social largesse.

A primary factor in the crisis is the oil price decline. But economists say the Chavez economic model of heavy subsidies, price controls and declining productivity had begun to collapse before the oil market went south.

But he is also hampered by his lack of political skills.

“Maduro doesn’t have the same charisma or the ability to personalize an election as Chavez did,” said Luis Lander, a retired political science professor in Caracas. “But even Chavez would have his work cut out for him this time.”

The polarization of Venezuelan society has favored chavismo, the socialist movement named for Chavez, in previous elections, with followers opting for its welfare programs over the uncertainties of a new government, Lander said. But hyperinflation, which this year could exceed 200% — the highest anywhere in the world, says Puente — has ravaged Venezuelans’ spending power and made the idea of change more attractive, he and other analysts said.

“With Chavez, no one questioned his leadership or his ability to resolve conflicts. But with Maduro we have had paralysis,” Lander said, citing the president’s dysfunctional 4-tiered currency exchange system and refusal to cut subsidies on food and fuel that cost the country an estimated $13 billion. Although the subsidies help the poor, they distort the economy, analysts say, when a commodity such as gasoline costs less than $1 for 20 gallons.

Some analysts go so far as to speculate that if the opposition wins two thirds or more of assembly seats, Maduro may resign, be forced from office by fellow party members or attempt something for which neither Maduro nor his predecessor Chavez never felt the need or desire: a reconciliation with opposition forces.

A landslide victory by opposition candidates could provide the political impetus for Maduro opponents to set a recall vote next year.

“We’re headed for a ditch. Almost half the people would leave the country if they could,” said political consultant Jesus Seguias. “Three more years of this government is not a viable option.”

Whether the opposition takes control of the assembly or not, Puente sees next year as being more dismal economically for Venezuela than 2015, because of a looming foreign debt default, a possible devaluation and even higher inflation.

Things could be so bad next year that Maduro may be forced to seek a multibillion-dollar aid package from the International Monetary Fund or some other source such as China, Puente says.

“The political costs to Maduro will be high,” Puente said. “But it’s the only way out.”

Mogollon is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.