With protests rocking Jordan, king accepts resignation of prime minister, names reformer as successor

Jordan’s prime minister, beset by popular outrage over tax hikes and a raft of other austerity measures, tendered his resignation Monday and is expected to be replaced by a former World Bank economist.

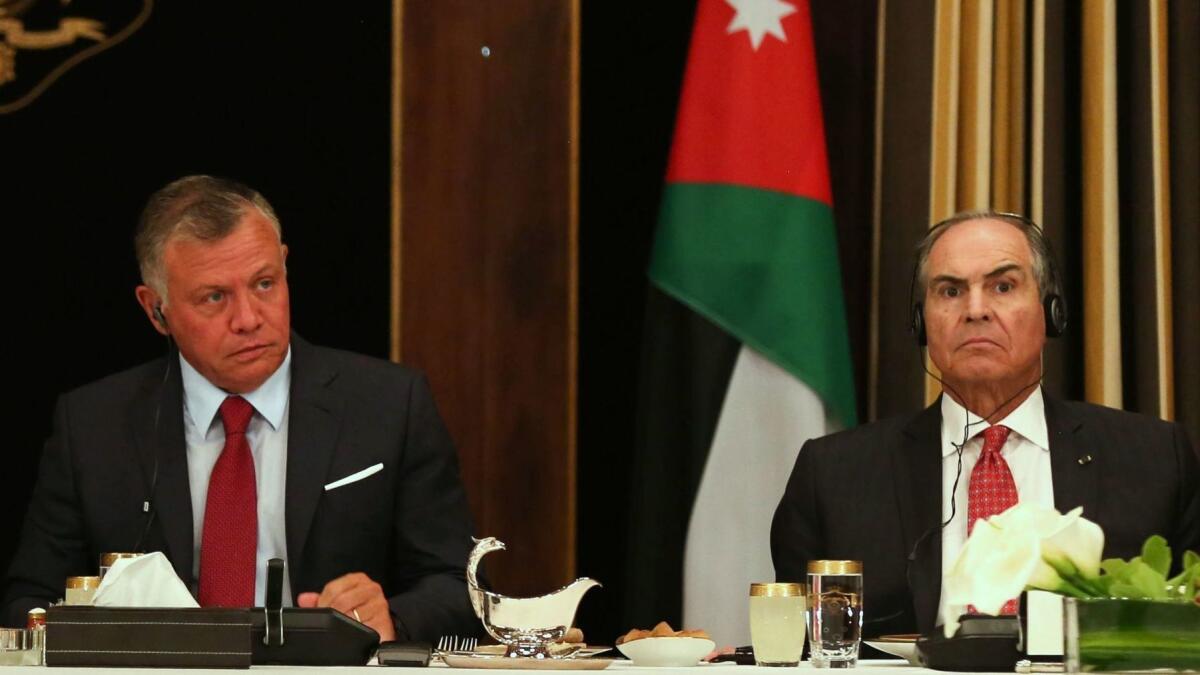

Hani Mulki stepped down after a meeting with the sovereign, King Abdullah II, following days of rare protests, the country’s biggest in years, that saw tens of thousands of people across Jordan calling for the government’s downfall.

Abdullah, who has the power to disband Cabinets and appoint prime ministers, is reported to have asked Omar Razzaz, the country’s education minister who was previously with the World Bank, to head a new government.

Mulki’s departure was the final act of a deeply unpopular prime minister who, though he spent only two years on the job, was often excoriated for pushing economic reforms demanded by the International Monetary Fund.

Although the IMF had granted Amman a lifesaving $723-million, three-year line of credit in 2016, it came with a caveat: Jordan would have to implement an austerity package aimed at reducing its national debt, which at $37 billion constituted 96% of the country’s gross domestic product in 2017, according to IMF data. The goal was 77% by 2022.

Mulki had enraged Jordanians at the beginning of the year by levying a sales tax on 165 items, many of them basic commodities that would affect the poor. But it was only the first step.

Fuel prices increased; water and electricity costs skyrocketed (the latter by 55%), while a wide-scale scrapping of subsidies saw the price of bread double overnight.

The hikes earned Amman the dubious distinction of being the Arab world’s most expensive city in 2018, according to a report by the Economist magazine. Meanwhile, salaries have remained stagnant for years,

The last straw came last month when Mulki proposed a 5% increase in the corporate tax. The measure would also seek to grow the country’s tax base from 4.5% to 10% of the population by lowering the minimum taxable income for both individuals and families.

Violators would face a barrage of punitive measures, including prison, a serious development in a country where tax evasion is rampant. (Last year, Jordan’s Income and Sales Tax Department estimated annual loss due to tax avoidance at more than $4.2 billion.)

The proposed tax bill faced fierce opposition from labor unions, which said it would impoverish the country’s already-eviscerated middle class.

Mulki, however, refused to back down.

Union leaders retaliated by calling for a general strike Wednesday that drew thousands (as it has every day since) to the prime minister’s headquarters in Amman’s diplomatic district, while demonstrations erupted in other cities.

Activists also took to social media, rallying support with hashtags that declared #WeHaveNoMoney and others.

The government, in a move that astounded even its staunchest supporters, introduced yet another round of electricity and fuel hikes.

With demonstrations reaching fever pitch, the king, who is the country’s ultimate authority but portrays his role as standing above the day-to-day minutiae of domestic affairs, ordered a freeze on any price increases.

Protesters were unimpressed and took to the streets again to insist Mulki leave and the tax law be withdrawn.

Many also accused the government of overspending and of endemic corruption, and complained that they received scant benefits from their tax payments.

The wave of unrest is a rare occurrence in a country often described as an island of stability in a notoriously troubled region.

It was largely spared the turmoil of the so-called Arab Spring protests in 2011, yet was still buffeted by their fallout: Millions of Syrian refugees streamed into the kingdom to flee the civil war tearing their country apart. The instability kept tourists away and made foreign investors wary; routes to Iraq and Syria were closed, in effect isolating Jordan from its export markets; and sluggish growth led to record unemployment. (Youth unemployment is thought to have reached 40%.)

In the past, Jordan, a poor nation with no oil and few exports, had weathered fiscal crises by utilizing handouts it received from the United States and Persian Gulf states. The kingdom has long been a key U.S. ally in the region.

This year, the U.S. signed a memorandum of understanding with Jordan that gave the tiny kingdom $6.37 billion over the next five years, not including aid packages for assistance in dealing with Syrian refugees.

Yet its traditional sources of support from the gulf dried up, especially after Abdullah was reported to have defied the dictates of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who is thought to have supported the transfer of the U.S. Embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

Mulki’s ouster spells the premature end of the seventh government in the last decade. It was yet another example of the palace’s sleight of hand, with the king disbanding or reshuffling cabinets in a bid to quell discord.

But it was unclear if Monday’s move would be enough.

“They can’t do yet another symbolic ‘sack the prime minister, bring someone else, get a policy statement that says the same thing as the last 10 policy statements,’” said Rami Khouri, a professor at American University of Beirut, in a phone interview Monday.

The sentiment was echoed by Sean Yom, a Jordan expert at Temple University.

“The government will still face pressure from above to implement financial austerity; simply being younger and more popular, as Razzaz is, doesn’t mean the Central Bank will suddenly discover 1 billion Jordanian dinars [about $1.4 billion] and realize it doesn’t have to cut subsidies or raise taxes at all,” Yom said in a chat message Monday.

“The heart of the matter is that Jordan is broke, there are no more crises to milk and financial decisions, like foreign policy, are made by a small group of unelected officials … who do not have to answer to parliament or the public — only the palace, really, and outside donors.”

Despite the government being disbanded, protesters came out again Monday night, though in smaller numbers than on previous days.

Bulos is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.