BAYOU BALLET : HARLEM SWAMPS NEW ‘GISELLE’

Black American singers have been portraying Germanic gods and Baroque noblewomen and Renaissance ingenues and 19th-Century courtesans for happy decades. But Arthur Mitchell, director of the Dance Theatre of Harlem, seems to think that black American dancers can’t validate comparable dramatic fantasies.

When he turned to good old, sweet old “Giselle” for his company’s first full-length classical ballet, he moved the action from its usual Rhineland let’s-pretend setting to the Creole society of antebellum Louisiana.

“I’m just making it relevant,” he rationalized. “Basically, I thought it would be silly to set it in Austria (sic) and for us to dress up as Austrians.”

Mitchell justified his textual transposition with some interesting historical research. “I found out that New Orleans during slavery was in many ways more a European than an American city, and that there was an affluent, free black society that itself owned slaves.”

He also took comfort in reports that “a European traveler had written that women in New Orleans would rather dance than eat.” Finally, he visited the South and “saw the Spanish moss, the oak trees, the honeysuckle, the bayous and felt this was the essence of Romanticism.”

The new “Giselle,” which received its West Coast premiere Thursday night at Pasadena Civic Auditorium, does indeed bear some surprising trappings.

Act I takes place in a l’il plantation inhabited by a recently freed slave, Madame Berthe Lanaux, and her gotta-dance-gotta-dance daughter, Giselle.

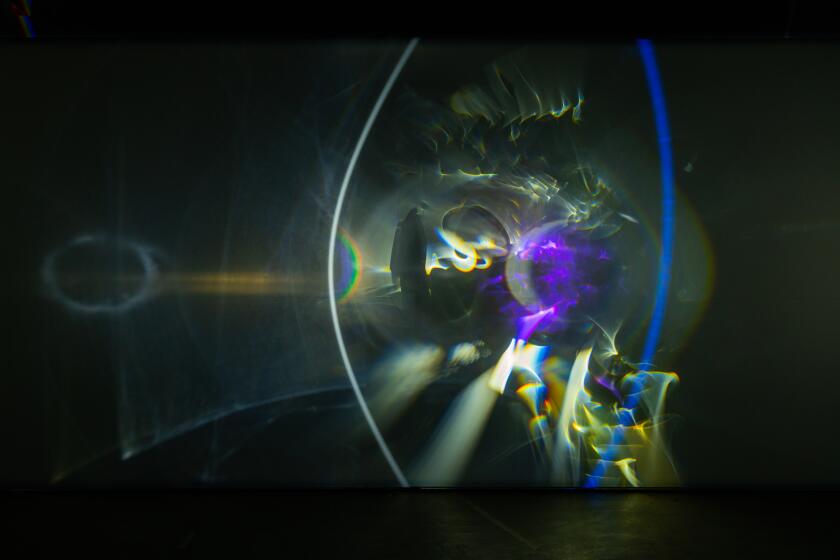

Act II takes place in a swampy mausoleum. Albert Monet-Cloutier--a k a Duke Albrecht--a black gentleman whose family has been free for several generations, visits his beloved’s tomb via picturesque ferry. It is as if he were boating the river Styx.

The vengeful, ghostly Wilis traipse through the murk not in the tutus for which their tippy-toe maneuvers were designed but in filmy, anachronistic, Isadora Duncanesque rags. Scholars say these costumes happen to resemble those used by Pavlova in 1910.

There are lots of details in the new scenario--concocted by Mitchell in collaboration with his designer, Carl Michel--that defy logical scrutiny. One doesn’t have to be an implacable purist to complain about a certain degree of silliness here, or to note that the dainty Adam score fails to accommodate the folksy Louisiana milieu, or to worry that distinctions get lost when the cad-hero is deprived of his official nobility.

Ultimately, however, none of this matters much. “Giselle” is strong enough to withstand gimmicky sets and costumes, not to mention narrative contradictions. And, in the final analysis, the complexion of the dancers is irrelevant.

What does matter is emotional compulsion. What does matter is brilliant dancing. What does matter is style. It is in these areas, alas, that the Harlem “Giselle” sags and flounders.

Frederic Franklin, a knowing survivor of the Markova-Dolin school, has staged the proceedings along traditional lines, and retained traditional cuts. The result is bland, dutiful, sometimes even perfunctory.

The participants wear their costumes proudly, execute their rituals carefully. They have not yet learned, however, to define and sustain character. They have not yet mastered the art of fusing theatrical projection with formal motion. They seem to think striking poses and remembering the right steps is enough.

Virginia Johnson plays Giselle Lanaux sweetly. She is a nice girl when she frolics with her friends, a nice girl when she stabs herself, a nice girl when she goes ever-so-slightly mad, a nice girl when she defies her ghoulish sisters to save the porteur she loves.

She dances neatly, most of the time, but seldom goes beyond dancing. There is little ardor in her revelry, little abandon in her amorous surrender, little agony in her dementia, little pathos in her reincarnation, little heroism in her transfiguration. This is only a sketch.

Eddie J. Shellman matches her by playing Albert as if by rote. He cuts an imposing figure, demonstrates ever-improving skills as a technician and functions as a stalwart partner at pas-de-deux time. He hardly begins, however, to define a complex personality--one has to read about that in the profuse apologia handed out to the press. Even more damaging, he often allows us to forget that Giselle is the most important force in Albert’s life.

Lorraine Graves must be the tallest Myrta in history, but not the most glacial, the most regal or the most effective when it comes to realizing Coralli’s formidable choreography.

Lowell Smith as the lowly Hilarion Guidry remains virtually undistinguishable from the presumably noble Albert. Judy Tyrus and Joseph Cipolla dispatch the erstwhile peasant duet with what now looks like misplaced elegance. Cassandra Phifer mimes Mammy Berthe so gutsily one wishes Franklin had retained the crucial passage in which she explains the phenomenon of the Wilis. As the once-aristocratic Bathilde, Theara Ward flounces like a nouveau-riche floozy.

Although Michel’s decors are storybook pretty, they are compromised by Shirley Prendergast’s inexcusably primitive lighting scheme .

Milton Rosenstock leads a wretched (or wretchedly under-rehearsed) pit band through the delicacies of the score as if he were a man in a hurry to get home. Under the circumstances, one can’t blame him.

For a curtain-raiser, the company mustered Balanchine’s “Square Dance,” in the old version that utilizes a caller. Listlessly performed, it did little but make a long evening too long.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.