Candor Stressed in Stage Account : Soviet Drama Spotlights Chernobyl Incompetence

Less than five months after the nuclear disaster at Chernobyl, a play that makes a searing indictment of plant officials is about to be staged in Moscow and other cities.

The play, “Sarcophagus,” breaks with the tradition of hiding problems from the public and boldly focuses on the incompetence and instances of cowardice that led to the April 26 tragedy, which spread a radioactive cloud across Europe and has claimed 31 lives.

It presents a plant director, for example, who leaves his post to evacuate his own grandchildren but fails to sound a general alarm. It also deals with safety equipment in disrepair and the absence of backup systems.

The play’s rapid appearance suggests strongly that it has the support of high-level Kremlin officials, if not that of Soviet leader Mikhail S. Gorbachev himself.

The title, “Sarcophagus,” is an allusion to the cement tomb now being built for the runaway reactor at Chernobyl, and it reflects the Gorbachev policy of glasnost, or candor on public issues.

Excerpts of the script printed in the newspaper Sovietskaya Kultura appear to put heavy blame on officials of the Ukrainian Republic, where the accident occurred. Leaders at higher levels in Moscow seem to be spared blame in the play.

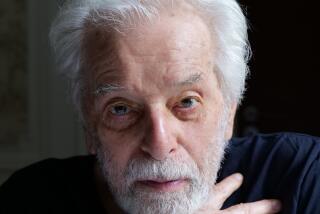

The author, Vladimir Gubarev, a science writer for Pravda, the Communist Party newspaper, has called the play a “frank and honest” portrayal of the Chernobyl disaster. In writing it, he said, he wanted to tell people what he had seen and how he felt “pain that lives in the soul.”

The full text of the play is to be printed in Znamya (Banner), a literary magazine. Several theaters have agreed to put it on the stage.

Overlooking Shortcomings

The excerpts portray local officials eager to place the Chernobyl reactor into operation ahead of schedule, even if that meant overlooking shortcomings and safety precautions. As a result, according to the play, highly flammable material was used for the roof of the reactor building, even though the material had been banned for more than 10 years on safety grounds.

The play is set in a hospital ward at a radiation institute where many of the top Chernobyl officials are patients, doomed to die but still able to answer the questions of a prosecutor.

“Why was that material on the roof?” the prosecutor demands of the plant director.

“We had a great stock of this material in storage, and the (power) station was badly behind schedule,” the director replies.

‘Fears Were Misplaced’

Later, a fire chief with the rank of general in the Ministry of Internal Affairs says:

“I thought it was just an ordinary fire. . . . I phoned the Council of Ministers of the (Ukrainian) republic but they told me my fears (that it might be something more threatening) were misplaced.”

As a result, he and his driver received a fatal dose of radiation when they drove up to the burning reactor.

“The general explained to me that even if the reactor blew up, the radiation would stay inside,” the driver says.

Perhaps the most poignant part of the play deals with a 36-hour delay in the evacuation of Pripyat, a city of 25,000 people a few miles from the reactor site. A heroic worker at Chernobyl asks the prosecutor, “When did they evacuate the city?” The prosecutor replies that it was on Sunday, a day and a half after the explosion started spewing radioactive particles from the reactor.

“They brought in 1,000 buses and quickly removed everyone,” the prosecutor goes on. “Just two and a half hours.”

Technician’s Question

“Why didn’t they immediately broadcast (news of the disaster) on radio?” the technician asks.

“It would take just one hour for everyone to leave the city on foot,” the prosecutor replies. “They waited for the arrival of the government commission.”

“Waited? Why? Could the commission decide otherwise?”

“No one had the courage,” the prosecutor says.

In the questioning of the factory director, a similar picture emerges.

Prosecutor: “You immediately understood what happened?”

Director: “Almost. In general terms.”

Prosecutor: “And disappeared?”

Director: “I just stepped out. You understand. . . .

Prosecutor: “Yes, I know. Your grandchildren were alone at your home.”

Director: “The work was already in progress on the (reactor) block. You know, my mother-in-law lives in a village eight kilometers from here. I thought I would dash to the village, bring the kids and be back right away.”

Prosecutor: “Why didn’t you sound the alarm in the city? Why not allow everyone to dash to the village? For them, it would be even closer. . . . They could make it on foot. You just had to broadcast the information on radio . . . to report what happened . . . and then there would be no need to wait for 24 hours for the government commission.”

Director: “It’s not all that simple.”

Prosecutor: “Of course, hopping into your Zhiguli (car), grabbing the kids and driving away. . . . Is that simpler? You understood better than most what happened, and, meanwhile, next morning, other kids were playing football in the open air, and they were selling vegetables in the streets.”

Neglect of Safety

In addition to personal irresponsibility, the play discloses neglect of safety equipment in the nuclear plant. A worker assigned to monitor radiation levels apologizes for not issuing warnings to other specialists but says his instruments failed.

Prosecutor: “Don’t you have any backup system?”

Worker: “Backup instruments? Where from? Even those I had were about 30 years old, and underwent God knows how many repairs. . . .”

The same theme is sounded by the plant director as he defends himself under questioning by the prosecutor.

Director: “Are you looking for a scapegoat? I am not going to be one. In the last 10 years, the quality of equipment in the nuclear stations has plunged. Why are the equipment and instrumentation totally obsolete? Why, for God’s sake, does it take the simplest order for repairs three months to get to the ministry and just as long to get back? I can give you dozens of such ‘whys,’ but why talk about the nuclear industry alone? Ask the hydro-power people, or the conventional power stations. If you think machine-building or electronics is better, you’re mistaken. It’s simply that the blister burst here.”

Regardless of whatever literary merit it may have, the play is expected to be a smash hit because of the enormous interest in the Chernobyl disaster and its consequences.

“People are still hungry to find the answer--how could such a thing happen?” one Muscovite said Tuesday. “This play may be even more reliable than a government report in giving us the reasons.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.