Of Poems and Paperbacks

Changes are taking place in the way the Los Angeles Times reviews poetry and paperback originals. Each change invites a word of explanation.

Among The Times’ 3 million Sunday readers, how many pass the entire year without reading a single poem? 2.5 million? A conservative guess, perhaps. But is it not odd to publish comparative discussions of whole volumes of poetry for readers who rarely read even a single poem? “Something for everybody,” a principle that has its uses for the reviewing of fiction, will not work here, for it is unclear what kind of poetry anybody wants.

Add to this problem the extremely fragmented character of poetry from the poets’ side. No school is dominant. There is no agreement on how many schools compete or what distinguishes one from another. The lack of overlap in anthologies that aim, unpolemically, to give the whole poetry spectrum is striking; to an editor, it can be almost paralyzing.

Now add to these two problems the inherent difficulty of writing well about poetry for a lay audience. Like music, poetry can be discussed in a specialized, technical language--precise, necessary and even exhilarating to the few who can follow. But like music, poetry discussed in ordinary language almost inevitably descends to cliche. This is not true of the best poetry criticism, of course; but even in the best criticism, the poems quoted--and how can you review poetry without quoting it?--fight with the prose that carries them. Prose and poetry are like bread and wine, each good in its own way. But prose about poetry is too often like bread with a little wine sprinkled on it.

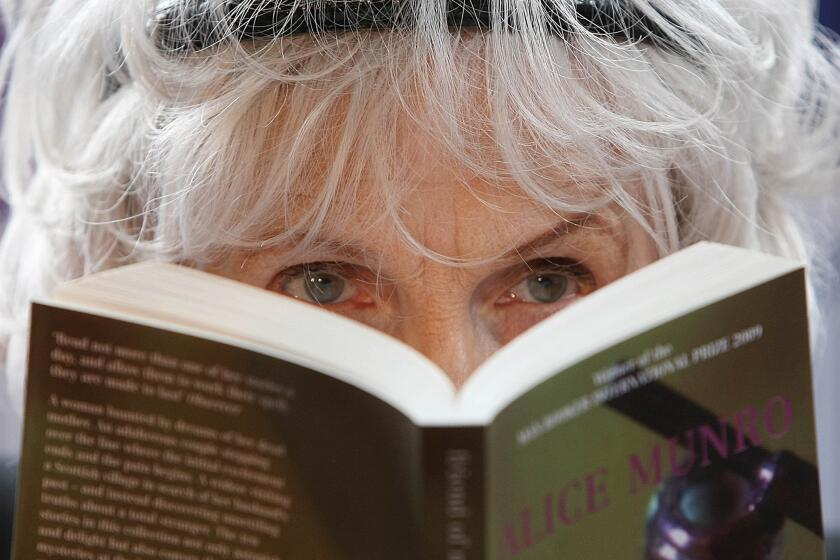

If all this be allowed about the readership of The Los Angeles Times, about the fragmentation of poetry in our day and about the difficulty of writing well about any poetry, then perhaps this change may be welcome: Instead of reviews of poetry, poetry itself.

We shall continue, yes, to review a few books of poetry as books, but our main coverage of the genre will be one, brief poem in each Sunday issue of The Book Review with just a word about its author and the new collection from which it has been taken. Something for everybody? Surely not, but perhaps something for somebody.

The phrase paperback original names a format and a point in the life cycle of a book. It does not name a genre, and, in fact, all genres have been published as paperback originals. Nonetheless, it may usefully be asked what kind of book publishers have most often published first, or only, in this format.

Not long ago, the kind of book that seemed most often to be published as a paperback original was the popular nonfiction title in a genre that did not require review; for example, the perennial J. K. Lasser tax guide.

More recently, there has been something of a hardcover nonfiction publishing explosion, not much remarked by the average reader but very happily noted by the publishing industry. Hardcover titles like “Iacocca,” “Fatherhood” and the earlier “In Search of Excellence” have sold in quantities that were once the preserve of inexpensive paperbacks. Perhaps because of this success, there now seem to be somewhat fewer serious nonfiction titles appearing as paperback originals.

Fiction, oddly enough, has been experiencing a reverse trend; namely, a vogue--partly European in inspiration--of publishing stylish literary fiction either in paperback original (often in a series with a standard, elegantly designed cover) or in simultaneous paperback and hardcover editions. Unlike bestselling popular fiction, these titles depend heavily on individual review attention.

In sum, publishers’ use of the paperback format is evolving in at least two different directions at once, and Jonathan Kirsch’s mandate in his long-running column on paperback originals has been increasingly difficult to define. Our solution might be described as a surrender to indefinition, or at least to informality.

As of April 9, Kirsch has become a new once-a-week reviewer in View. Appearing every Thursday, he will preside over a space reserved, but only informally, for nonfiction paperback originals and not rigidly barred to hardcover titles. His review will be, as it were, a social science complement to the natural science review that Lee Dembart has been writing on Tuesdays.

Kirsch, a lawyer trained in history, is the author of two books and dozens of magazine articles. As many but perhaps not all Times readers will know, he is the son of the late Robert Kirsch, who was The Times’ book critic for more than 20 years and in whose memory The Times presents each year a literary prize.

The Times Monday-through-Friday reviewers are now, in order of appearance each week: Carolyn See, Lee Dembart, Richard Eder, Jonathan Kirsch and Elaine Kendall. May the spirit of Robert Kirsch preserve them all in wit, style and judgment.

Search for the Perfect Pasta

by William Matthews

Little hats, little bow ties, little bridegrooms

with and without grooves, tiny stars, little seashells,

little ribbons, sparrows’ tongues, little Cupids,

little rings, tiny pearls, little chickens, tiny worms--

the world shrunk to bite size by gluttony and Italian’s

genius for diminuendo: piccolo, piccolino, dwindle

and gone. Too small to see, like the exact

discriminations we herded from one hill town

to the next: the tagliatelle were better in Todi.

Replete in our rented car, drilling the dark homeward,

we’d talk in switchbacks up the mountain

about women and marriage, making rueful

contrasts and comparisons, as if we weren’t single

by terror, as if marriage were an art and we

the victims of our own high standards for our work.

From “Foreseeable Futures” (Houghton Mifflin: $13.95; 50 pp.), the seventh collection from a poet who is currently writer in residence at the City College of New York and president of the Poetry Society of America. ( 1987 William Matthews, by permission.)

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.