D.A.’s Prosecution of Molestation Case Embitters Officers

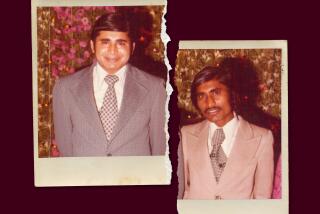

To the police officers who spent six weeks investigating complaints about Don Ray Moore, there was no question that he had been molesting fifth-graders at the South-Central Los Angeles public school where he had taught for 16 years.

They acknowledge, however, that the case against Moore had problems when they took it to the district attorney’s office in May, 1986. They had no physical or medical evidence, no incriminating statements from Moore and virtually no corroboration from adults.

But they had crime reports from 17 children who claimed that Moore was fondling female pupils aged 10 and 11. They had interviewed the students, and they believed them.

Case Rejected

Yet after reviewing the allegations for seven months, the district attorney’s office rejected the case against the veteran teacher. Members of the Los Angeles Police Department’s sexually exploited child unit were astonished and infuriated.

The district attorney’s office eventually brought other felony charges against Moore, 53, but only after the Los Angeles city attorney’s office entered the case and asked the police to investigate further.

The long delay and the handling of the initial allegations have left a residue of bitterness between police investigators and deputy district attorneys who specialize in child abuse.

Moore, meanwhile, was removed from his classroom at 97th Street School after allegations were made against him and he was placed on unpaid administrative leave. He failed to appear in court for an arraignment last month and remains at large.

Detective Ralph W. Bennett, who heads the Police Department’s sexually exploited child unit, said he believes that the district attorney’s decision to reject the initial case was “political,” a legacy of the unwieldy, controversial McMartin Pre-School case and the embarrassment it has caused.

That case was thrown into turmoil when Dist. Atty. Ira Reiner dismissed charges against five of the seven teachers who had been charged with molesting 15 children at the Manhattan Beach preschool. Then one of the original prosecutors, who was fired after he publicly voiced his belief that most of the defendants were innocent, made a deal with two film makers to tell his story and testified for the defense in a pretrial hearing.

“We don’t want another McMartin monstrosity,” Bennett quoted a prosecutor as telling his investigators, Detective Gary Lyon and Officer Stan Nalywaiko, during a meeting about the Moore case.

Members of the district attorney’s office deny that the McMartin case ever came up in their discussion with investigators. They say they had sound legal and ethical reasons for refusing to file the initial case against Moore.

Bennett, however, is convinced that “there is a totally different atmosphere under Ira Reiner on child sexual abuse.”

‘Will Not Shy Away’

Taking umbrage at this criticism and noting that no high-ranking police official has complained about the Moore case, Chief Deputy Dist. Atty. Gilbert I. Garcetti said: “We continue to handle incredibly complex child abuse cases. . . . This office has not, and will not, shy away from handling those types of cases.”

Nevertheless, there were several unusual features in the way the district attorney’s office handled the Moore case:

- It took a full seven months for prosecutors to reject the case. In an interview, Deputy Dist. Atty. Jane A. Blissert, the prosecutor assigned to interview the children, blamed the long delay on heated disagreements within her office.

- Last October, Blissert’s boss, Deputy Dist. Atty. Ronald Ross, then head of the unit specializing in sexual crimes and child abuse, decided to go ahead with the prosecution, even though Blissert and her immediate supervisor, Deputy Dist. Atty. Rita A. Stapleton, opposed it. LAPD Detective Bennett was told the case would be filed.

- After Ross’ decision, the case worked its way up through the top brass of the DA’s office, finally reaching Garcetti, the No. 2 man. Six prosecutors met with Garcetti over a two-day period and went over the case “child by child, count by count,” Stapleton said.

- Garcetti himself decided in December to reverse the earlier decision and reject the case.

The dispute aside, the handling of the Moore case underscores the special problems inherent in child molestation cases, when the evidence is based almost entirely on statements by children. In such cases, the decision to file usually boils down to a single question: Will a jury believe the children?

“If we can’t prove (the charges) in court, we have no business filing,” Stapleton said.

Stung by the district attorney’s rejection, Bennett took it to the city attorney’s office--and got a strikingly different response.

Paddling Boys

Earlier this year, that agency, which can only file misdemeanors, charged Moore with 29 counts, including the illegal paddling of four boys.

“I felt there was more than enough evidence,” Deputy City Atty. Vanessa Place said.

Since the original crime reports were mostly from children in Moore’s 1984-85 and 1985-86 classes, Place asked police to conduct further interviews with children from earlier classes. Allegations from additional victims would demonstrate a pattern of behavior and blunt defense arguments that the children were conspiring against their teacher.

Bennett said his men had wanted to do these interviews from the outset but that Stapleton, alluding to a “McMartin monstrosity,” told them that further investigation would amount to “useless overkill.”

‘Manageable Parameters’

At first, Bennett said, the reference did not seem distressing. “We believed they wanted to keep the (Moore) case within manageable parameters,” he recalled. At the outset of the McMartin case, 41 children were scheduled to testify to hundreds of molestation counts.

Stapleton denied making such comments and said she never tried to prevent police from looking for additional victims.

“I never told them not to do more investigation,” she said. Later, however, she did tell investigators that “the problems I saw had nothing to do with the number of kids and couldn’t be cured by bringing more children into it.”

As a result of the new interviews, police turned up six more alleged victims as well as incriminating letters, telephone records and corroboration from parents.

On July 27, the district attorney’s office filed 21 counts of felony child molestation against Moore, including sexual intercourse and oral copulation with a 12-year-old at his Redondo Beach home as well as incidents involving three other children.

Fondling Female Students

Complaints that Moore, a 20-year veteran of the school district, was fondling female students first surfaced in March, 1986, through a letter written by one boy and left for a teacher, and another letter to a teacher signed by half a dozen other pupils.

In accordance with office policy, Deputy Dist. Atty. Blissert interviewed all the children the police had talked to. In a 34-page memo, she cited numerous problems with vagueness, lack of corroboration and inconsistencies.

“While the general overall picture here is one where numerous children were molested and numerous other children saw it, problems arise in trying to sort out specific incidents that have sufficient detail to file and have witnesses’ corroboration,” Blissert wrote.

Recanted Complaints

Two children recanted their complaints and said that the children were ganging up on Moore, according to Blissert. “A number of kids said, ‘I told my mother,’ but their mothers said, ‘No, you didn’t,’ ” Blissert said.

Such “internal” problems with the case would not be remedied by locating victims from other school years, Blissert said. “Our feeling is that wouldn’t change the complexion of what we had with (the original) children. . . . I still feel that way.”

Deputy City Atty. Place was less troubled by the inconsistencies and the absence of details. Under her theory of the case, the molestation took place repeatedly, making it less surprising that the children’s accounts were often vague.

“If an event happens over and over, I’m not going to remember details,” she said. “You tell me what you had for lunch three weeks ago.”

‘No Witness Corroboration’

In her “declination” memo explaining why the case was turned down, Blissert had written, “Children relate five incidents to which there is no witness corroboration, despite the fact that the touching occurred in class in the presence of other children.”

But Place obtained a seating chart of the classroom showing that the children had been seated face to face while Moore sat in the back of the classroom. From that spot, she theorized, he could fondle individual girls without being seen by the others.

She also found it significant that, according to a crime report, a substitute teacher unearthed a pornographic magazine titled “Introducing Young Girls to Sex,” among things that Moore left behind at the school. The magazine itself was discarded, Place said, but the substitute teacher and principal can testify to its discovery.

Far From ‘Perfect’

Acknowledging that her case is far from “perfect,” Place said: “I would need to convince the jury to think like children. (The inconsistencies and contradictions) don’t make sense to an adult, but they do make sense to a child.”

Deputy Dist. Atty. Stapleton, who no longer prosecutes child abuse cases, said she has no regrets about her position on the original Moore case. “I know our decision was not politically motivated but was based on our best ethical judgment at the time.”

But she said police are “understandably upset” about the way the case was handled.

“I think very highly of those investigators and of Ralph Bennett,” she said. “I am sorry about what appears to be absolute miscommunication in this case.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.