Newport Pair’s Mini-Empire Unravels Into Fraud Charges

Available: seven apartment houses containing more than 1,600 units ripe for quick conversion to condominiums.

Terms: reasonable. No money required. Cash will be provided to cover all closing costs and first year’s mortgage payments.

It may sound too good to be true, but that’s the deal that jilted creditors claim Robert Buceta envisioned for himself, and then proceeded to implement in financing the purchase of residential real estate worth tens of millions of dollars from Florida to Southern California.

After Buceta defaulted on the loans, a federal grand jury in Los Angeles found another way to describe his Midas touch in real estate: too good to be legal.

Prosecutors allege that little, if any, work was done to carry out the condominium conversion plans. Those lenders who were willing to talk about their dealings with Buceta claim they have been left holding the bag for a minimum of $28 million in unpaid loans.

Buceta and his wife, Patricia L. Thibault, have pleaded not guilty to a federal indictment charging them with fraud and conspiracy in what U.S. Atty. Robert C. Bonner has called “one of the largest and most far-reaching fraud schemes ever perpetrated in Southern California.” They face a maximum of 142 years in prison if convicted on all counts.

Last week, Buceta hired noted criminal attorney Howard Weitzman to represent him in the case. Weitzman, who was John DeLorean’s lawyer in the trial that resulted in DeLorean’s acquittal on drug-trafficking charges, could not be reached for comment.

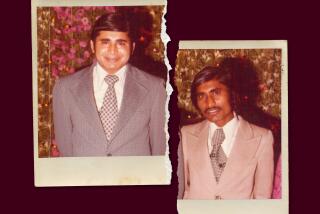

Buceta, 39, has lived and worked in Newport Beach for years and has been the target of numerous lawsuits by people who lent money to him or extended credit to him.

Both he and his wife, who is represented by a different attorney, have repeatedly declined to be interviewed. But interviews with dozens of people familiar with their financial dealings, as well as a review of claims in court cases on file, provide a picture of a one-time real estate prodigy whose reach far exceeded his grasp.

Although his name is now well known in financial circles in Orange County, Buceta, a native of Argentina, is still a mystery to many people familiar with his case.

Buceta’s early career was as a relatively low-profile Los Angeles real estate agent and broker, according to lawyers who have looked into his background. He was 35 when he first began putting together the deals that would make, and ultimately break, him.

One former business associate remembers that Buceta worked out of the posh offices of Capital Properties, in which he and his wife served as general partners, at 4400 MacArthur Blvd. in Newport Beach.

On a desk, Buceta kept a large Bible. His religion--Buceta described himself as a “born-again” Christian--was openly espoused, and his religious sentiments pervaded his business dealings, a former associate said.

“He would say a little prayer at the beginning of a business meeting, and he would cite a verse at the end,” said the former associate, who agreed to an interview on the condition that his identify would not be disclosed.

“You had to pray before you had a meeting,” he said. “Back in those days, they prayed over everything.”

The Bucetas have one child, a 5-year-old daughter, and they remodeled a large room in the executive suite for her use.

“They converted one of the rooms into a nursery for their brand new baby,” the former associate said. “They had Jungle Gyms, all sorts of equipment and everything. And they had a nurse who was there all the time.”

From that unorthodox command post, Buceta persuaded thrifts and other financial institutions as far away as Texas to help him buy property, according to court documents. His forte was acquiring apartment complexes for conversion to more valuable condominiums.

Working with real estate agents, brokers and mortgage bankers, Buceta collected a list of apartment properties that, in theory at least, could be converted quickly.

The Bucetas appear to have been wildly successful in persuading others to trust them with money.

In February, 1983, Buceta closed escrow on the purchase of a 102-unit complex in Escondido called Rock Springs, according to court documents. The deal was funded by a $4.5-million loan from State Savings of Stockton, now American Savings & Loan of Irvine.

Five months later, Buceta was the new owner of Ginger Cove, in Tampa, Fla., with 288 units, the indictment against them says. The purchase was financed by a series of loans totaling $12.9 million, also from State Savings of Stockton.

By November, 1983, Buceta was about to embark on a quintuple roll around his personal Monopoly board.

Between Nov. 8 and Dec. 30, he and his wife closed escrow on five major purchases, court documents show. In seven weeks, they added 1,021 units in Colorado, Texas and Florida to their holdings.

More than $43.6 million in loans funded those purchases. The Bucetas, according to the indictment, were the proud owners of a mini-empire in real estate--owing almost $62 million in loans on what appeared to be $85.5 million worth of property.

They had done it all without having to pay a penny in down payments, according to the indictment.

Within six months, by mid-1984, some lenders realized there were serious problems developing with Buceta’s deals, but it was some time before private lenders and government investigators concluded that Buceta’s defaults were not just bad business.

The Bible-quoting wheeler-dealer had set up sham escrow transactions using fraudulently inflated appraisals, misrepresented that the loan proceeds would be used to renovate the properties and lied about his financial status and tax returns in applying for the loans, according to the indictment.

At the heart of the alleged scam was what lawyers call “the flip.”

A double escrow is used to pull it off. The property in question changes hands twice at the same time, with the first purchase at fair market value and the second at a much higher price. On the same day, Buceta allegedly would buy the property through a corporation he controlled and then sell it to himself, often at nearly double the price of the first transaction.

The ultimate victim in such a scheme is the financial institution that lends money based on the second selling price, believing that is the true value of the property. The first purchase and the fact that Buceta controlled the entity from which he bought the property were concealed from the lenders, according to the indictment.

Also lending apparent legitimacy to the deals, court documents show, were the appraisals submitted for the second transactions, when Buceta bought the property from the corporation. Instead of a single appraisal for an apartment complex that he was buying, Buceta arranged individual appraisals of each of the units to be converted to condominiums, which, when added together, inflated the value of the property, prosecutors have alleged.

Armed with what looked like attractive deals, Buceta needed just one finishing touch, according to federal prosecutors: a personal financial face lift. He cooked up false tax forms and financial statements to make himself appear credit-worthy, according to the indictment.

Buceta had no intention of converting the apartment complexes to condominiums, the indictment alleges.

Some representatives of Alamo Savings & Loan Assn., which funded Buceta’s purchase of a 300-unit complex called Park Place in San Antonio, share that sentiment.

“He came in and bought these properties, skimmed and took all the rents, and didn’t make the loan payments,” said Ronald King, an Alamo lawyer. “He took all the income and never made the debt service. All he did was take everything.”

Alamo, operating at a loss, is now under supervision by the state, one of dozens of troubled thrift institutions in Texas. Alamo won a $6.9-million judgment against Buceta, which was recorded last year in Orange County. The transaction was not one upon which grand jurors in Los Angeles based their criminal charges, however.

Lenders are not eager to discuss their dealings with Buceta or the alleged swindle’s impact on their finances. In addition to Alamo Savings, two out of four of the thrifts and financial institutions named in the indictment against Buceta are out of business, and a fourth is deeply in the red.

For State Savings of Utah, which lent Buceta almost $20 million, “the losses sustained (in the Buceta loans) played some role” in its bankruptcy, said Herschel Saperstein, the receiver.

But he added: “It would be very difficult to say that this caused the downfall of the institution. It’s often a series of transactions.”

Sun Savings of San Diego, now in receivership, lent Buceta $12.4 million for projects in Denver. According to documents on file in Orange County Superior Court, Sun Savings has obtained a $2-million judgment against Buceta.

The assets of a third lender, Sko-Fed Mortgage Corp. of Newport Beach, have been acquired by Dallas-based Sunbelt Savings Assn. of Texas. Some $26.5 million in loans were disbursed to Buceta in 1983 and 1984, according to the indictment, but no losses were specified.

A fourth lender, the former State Savings of Stockton--now American Savings & Loan, the troubled thrift based in Irvine--lent Buceta $17.8 million on property that Buceta acquired for $13.2 million, according to the indictment. Buceta allegedly told the firm that he had bought the property for $24.8 million.

A spokesman for American Savings & Loan said no litigation has been filed and none is contemplated, adding that no information on losses is available.

Alamo, the Texas savings and loan, is ahead of the other major lenders, having obtained a judgment against Buceta. But a member of a San Diego law firm hired to collect it has had no luck.

“In this case, we didn’t do very well. We’re not going to get a cent--we know that,” she said. “All his property is in foreclosure.”

For now, the Bucetas own a home at 1 Rue Biarritz, in the fashionable Big Canyon area of Newport Beach.

But the property is in foreclosure and is encumbered by four trust deeds representing at least $545,000 in debts, according to Orange County property records. Buceta is in arrears on two years’ worth of property taxes--a total of $12,000. The home is estimated to be worth $650,000 to $750,000.

Creditors could schedule a forced sale of the home as early as next month.

Los Angeles attorney Richard Reinjohn, Buceta’s brother-in-law, has attended several court hearings but does not represent the Bucetas.

“From what I know, I just can’t believe it. I just can’t believe that these guys (prosecutors) think this is that big a deal. I don’t comprehend that at all.”

A lawyer in Bonner’s office earlier this month said investigators have traced $1 million of the loan proceeds to bank accounts in Canada--a claim Reinjohn rejected. The Bucetas “are trying to survive, but they don’t have anything,” Reinjohn said.

The Bucetas’ dealings, he said, are simply business ventures gone sour.

“It’s as simple as this: If these projects all had gone forward, nobody would have said a word. They didn’t, and everybody looks for a scapegoat. Here’s the scapegoat.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.