Pharmacies Are Dropping Out of Programs : Stores Say Prescription Plans Don’t Fill the Bill

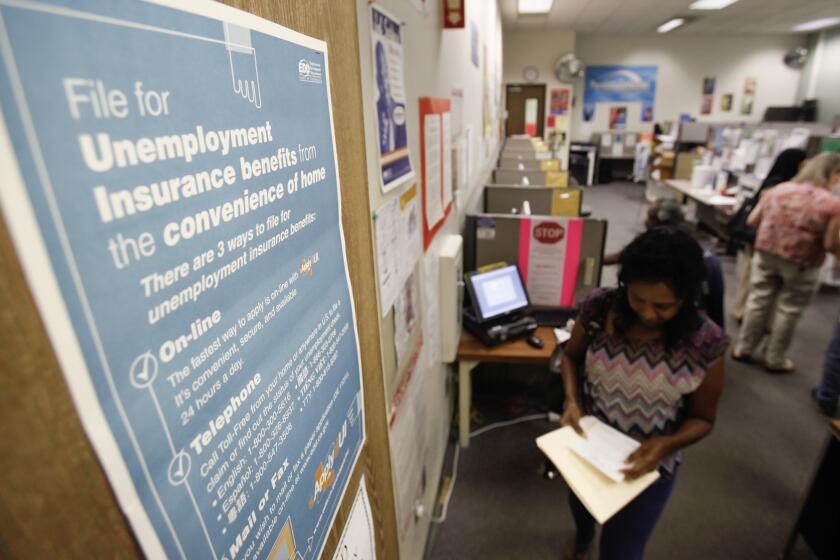

An increasing number of drugstores across the country are refusing to fill prescriptions paid for by certain health plans because the arrangement is becoming unprofitable.

Industry executives report that drugstores are dropping their prescription plan business at an alarming rate. This trend raises questions about a benefit that has allowed many consumers to pay minimum fees of about $2 to $5 for each of their prescriptions. Such plans represent one-third of the prescription drug business nationwide, according to the National Assn. of Chain Drug Stores.

Industry executives say the problem is widespread, involving both the big drug chains and the smaller independents, who still fill 70% of all prescriptions nationwide.

People covered on such employer-paid health insurance plans pay their fee for prescriptions after presenting a plastic identification card to a participating pharmacy. The pharmacy filling the prescription is later reimbursed for the balance of the charge by a firm functioning as what is called a third-party payer. The third-party payer, in turn, is reimbursed by either an insurance company, an employer or a health maintenance organization.

Consumer in Cross-Fire

Drugstore executives say their firms can no longer afford to participate in some of the prescription plans because these plans’ third-party payers have made deep cuts in the reimbursements they are willing to pay.

The consumer, then, is caught in the cross-fire. On one side are the drug retailers, who say they cannot afford to stay in business if they do not make enough money to cover their operating costs. On the other are the HMOs, unions, insurers and employers who, in the struggle to keep the costs of drugs and other health-care expenses under control, have turned to third-party payers to reduce the costs of providing for prescription drugs.

Paid Prescriptions Inc., a Fair Lawn, N.J., firm that processes prescription plans for 20,000 different insurers, has received letters from pharmacies around the country “advising us that they are no longer participating because the reimbursements are insufficient,” said David Sackett, executive vice president and chief operating officer. “In the last two years, I didn’t get any (such letters).”

“Ultimately, the American consumer and health care delivery system are harmed,” said Ronald Ziegler, the former White House aide who is now president of the National Assn. of Chain Drug Stores.

“We get calls on a daily basis from a woman in West Virginia who had to drive 15 miles out of her way because we wouldn’t fill her prescription,” said Charles C. Conaway, vice president for third-party administration at Rite Aid, the country’s largest drugstore chain. In the past four to five months, Rite Aid has refused to participate in a total of 50 prescription plans serving hundreds of thousands of people.

Lower Wholesale Prices

The reimbursement contracts for third-party payments have traditionally been based on the cost of the drug plus a flat dispensing fee, usually $3. The generally accepted practice has been to use “the average wholesale price” as a way to determine the cost of the drug. Those prices have been rising at a rate of about 10% a year, however. For example, then, a drug with a $15 average cost this year would probably be $16.50 next year.

As the drugstore chains become bigger, though, they are able to buy the drugs for much less than the average wholesale price. Insurers and others argue that they should benefit from such bulk purchases and have been demanding discounts of 5% to 15% off the average wholesale price.

Sackett cited a study commissioned by Mack Trucks that found, for example, that drugstores purchased many brand-name prescription drugs for 15% less than the average wholesale price and that they paid as much as 50% less for generic compounds.

Perhaps the most vocal among the drugstore chains has been Rite Aid, which fills about 60 million prescriptions a year. The retailer, which is based in Shiremanstown, Pa., conducted a study last year of 19.8 million prescriptions and found that it was making 72 cents profit on an $18.56 prescription through a plan that reimburses the average wholesale price and the standard $3 dispensing fee. When customers paid cash, according to the study, the retailer’s average profit was $1.48 per prescription.

Pressure Plays Role

Drugstores also argue that it costs more to fill prescriptions of third parties than of cash customers--in Rite Aid’s case, 77 cents more. In addition to the administrative paper work involved in processing claims, the stores often are not paid for at least 30 days, industry executives said.

The configuration of the local markets can also be a factor in the battle. In areas such as Washington, where there are a few dominant drug chains and no dominant employers, the retailers have been able to fight off attempts to push down reimbursements. But, according to industry executives, in areas such as Detroit that have a few dominant employers and any number of drugstores, the stores have been forced to accept lower rates of reimbursement.

In other cases, public pressure seems to have played a role.

In Baltimore, 50,000 active and retired city employees last fall found that more than half of the area’s 160 participating drugstores were refusing to fill their prescriptions because their insurance carrier, Prudential Insurance Co. of America, decided to cut payments to the pharmacists by 10%. After protests from the retailers and city officials, however, Prudential eventually backed down.