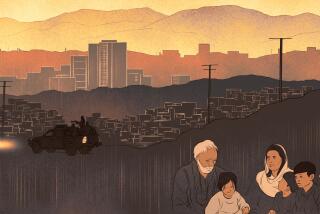

EPILOGUE / ETHIOPIAN AIRLIFT : In Judean Hills, African Emigres Say They Are Victims of Broken Promises

Occupied West Bank--Tovah Kassa cradled a snuffling child in her arms, and a look of despair crossed her dark, tattooed face.

Chunks of dried bread lay on the living room floor and on the Spartan furniture of the government-issue, cold-water flat--remnants of the morning meal for her seven other children. There is never enough food, she complained in broken Hebrew, and there is no work.

For Kassa, an Ethiopian Jew, the Promised Land is this fenced settlement of 5,000 people in the rocky Judean hills outside the overwhelmingly Arab town of Hebron. But she and other Ethiopians say it is a place of broken promises.

Thirty Ethiopian families were transported to this settlement by the Israeli government in the dramatic Moses I airlift from Sudanese refugee camps in the mid-1980s. Most of the 11,000 Ethiopian immigrants have been placed in reception centers and towns in Israel--Ashkelon, Netanya, Beersheba--and a few hundred in Jerusalem. Kiryat Arba, a militant Jewish outpost in the occupied West Bank, is more isolated, but the problems of the Ethiopians seem to be the same everywhere.

The Ethiopians say they came to Israel eagerly, and with great fanfare, but have been neglected since. Mesfin Ambaa, an official of the Assn. of Ethiopian Immigrants, a support organization for the community, said his demands for greater aid--jobs, better housing, money to fly out relatives still in Ethiopia--have been ignored.

Ambaa, talking with a reporter in a cramped office in downtown Jerusalem, said officials of the Ministry of Immigration and Absorption “don’t care about us.”

“We write the Absorption Ministry about the problems,” the tall, thin Ethiopian said, “and they say, ‘You solve it.’ We talk to Knesset (Parliament) members. They promise to help. They come out and have their pictures taken with us. And then they leave. Nothing happens.”

His chief complaint, like those of the Ethiopians at Kiryat Arba, is lack of jobs and housing. Now, Ambaa said, with the tide of Soviet immigrants coming to Israel, he is more pessimistic.

“They get apartments,” he said. “We don’t.”

Israeli officials insist that the Ethiopians are getting a fair shake. Boaz Shviger, an adviser to the Jewish Agency, which deals with the immigrants, told a Jerusalem Post reporter, “We do everything we can to see that the Ethiopian immigrants get what they need in aid . . . in preparation for the time when they can start their independent lives.” He denied that the Soviets are receiving agency funds earmarked for Ethiopians.

Whatever the problems of the Soviets, the Ethiopians have desperate concerns. Many have relatives still living in Ethiopia’s Gondar province, which is ravaged by civil war and drought. Without jobs here, the new Israelis cannot send enough money home to bring out their families.

At Kiryat Arba, 33-year-old Zemen Negess briefly found work at a pistol assembly plant but has been jobless since the plant closed. Like others here, he seems bewildered.

“They brought us straight from Ben-Gurion (airport) to this place and left us,” he said. “We were supposed to be trained, but there’s nothing yet. I don’t want to live here. There’s no work. We can’t go into town (Hebron). The apartments are in poor shape. Only Ethiopians live like this.”

Negess said that officials at the Ministry of Immigration and Absorption told him he could leave Kiryat Arba if he bought an apartment in an Israeli city.

“They said I could take a mortgage,” he told a reporter. “A mortgage! I have no money.”

For now, the Ethiopian adults of Kiryat Arba concentrate on their children.

They have learned a little Hebrew from their children, who attend special classes. Among themselves, they speak their native Amharic.

“Maybe for the next generation it will be better,” said Ambaa, the community worker from Jerusalem. “But now even the children are unhappy. Kids want to do everything. They want to do what their Israeli friends do. But that’s not possible yet.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.