Karachi Social Worker Fills Gap in Services for Poor in Pakistan

It’s not a lesson anybody would want to teach a child, but for Shakir Hussein Shah making a grab for somebody’s wallet--and getting caught--may have been the best move he made in his 13 years.

Having no suitable facilities for the youth, the police handed Shah over to a privately run home for boys. Now he lives in a dormitory with other youngsters, attends school at the home and is being trained as an electrician.

“It’s a better place because I’m learning here,” the reformed street hustler and pickpocket said recently as he worked with a screwdriver and wires to fashion a light bulb tester. “It’s better than my home.”

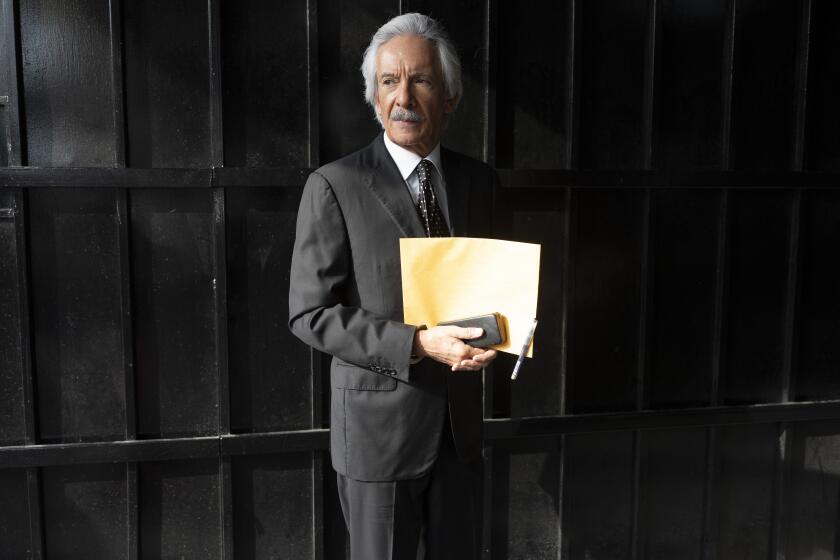

The man behind Shah’s rehabilitation is Abdul Sattar Edhi, a 58-year- old social worker whose efforts on behalf of the poor and disadvantaged in Pakistan have earned him the affectionate title of “the Mother Teresa of Karachi.”

Nearly 30 years after he launched his career by opening a medical dispensary, Edhi has become a symbol of hope amid the violence and political turmoil of the city, slowly building a diverse private welfare system to fill the void left by government.

Through organizations financed by private donors, he operates everything from an air ambulance service to a treatment clinic for drug addicts. His centers provide shelter for battered wives, homes for orphans and runaways and proper burials for the dead unwanted.

“Everybody has the feeling that when he goes from this world, he should leave behind something. When I go from this world I want to leave behind something of benefit to others,” Edhi explained recently while working in a clinic along the narrow alleyways of the old city.

Edhi, seeking to win the trust of a people jaded by political factionalism and self-interest, avoids government money. He believes that the act of people making small contributions helps build the kind of social concern he wants to help instill in Pakistan.

“Through social work I am trying to imbue a spirit of cooperation so people will love each other,” he said. “If I succeed in bringing a new social cooperation among the people, then the future generations will be influenced to work along these lines.”

Although he controls a budget of several million dollars, Edhi, a compact man with a gruff voice and a salt-and-pepper beard, lives an austere life. He wears the baggy, pajama-like clothing of the people he helps and has said he buys a bar of soap once every three years.

Only 5% of the funds he collects go for administrative costs. The rest goes to support the vast welfare system he runs along with his wife, three adult children and more than 1,000 employees and volunteers.

Although much of his time is spent traveling and administering the operation, Edhi remains involved in the work of his clinics, driving ambulances and bathing the dead for burial according to Muslim custom.

“I am available 24 hours for this work,” he said.

As he spoke, an ambulance arrived bearing the shrouded body of a woman who died during the day without relatives to tend to her funeral. Edhi’s daughter disappeared into the mortuary to wash the body for burial.

Despite his accomplishments, Edhi has yet to find an end to his mission. Recently he embarked on his most ambitious project to date--constructing 115 mini-clinics, each with an ambulance and doctors on duty, at 30-mile intervals along the nation’s major highways.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.