Miracle Recovery Sends Double-Lung Recipient Home

Last year, Theresa Steveley was gasping for breath and developing pneumonia every other week because of her diseased lungs. The average life expectancy of a cystic fibrosis patient is 30 years, so this 31-year-old cystic fibrosis patient was lucky be alive, doctors said.

At her home in Hillcrest on Monday afternoon after being released from the hospital, Steveley said she felt like she had been hit by a truck, but she was happy and, most important, breathing easily.

Three weeks ago, Steveley became the first person to undergo double-lung transplant surgery in San Diego.

“It’s pretty traumatic,” Steveley said. “It was a big operation. I felt like a truck ran over me. I’m just gathering up my strength, and the more mobile I get, the better I feel. It feels pretty good to breathe through my lungs, considering.”

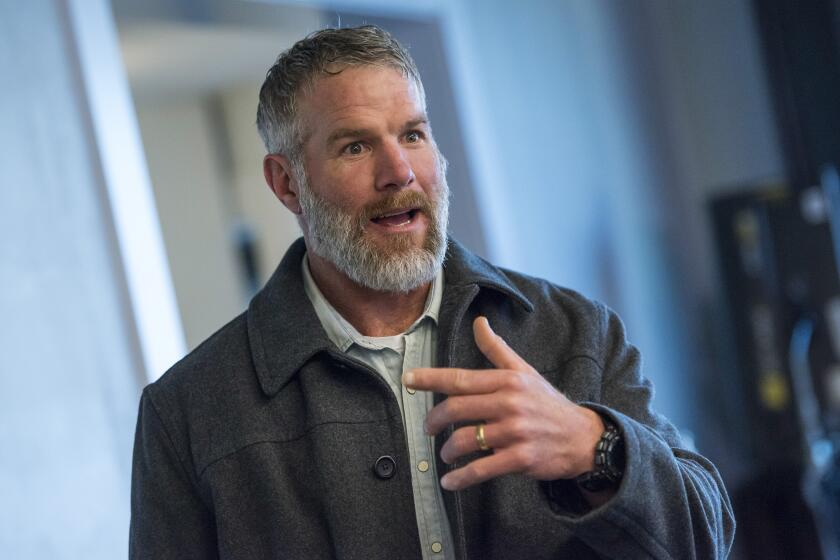

Dr. Stuart Jamieson, the UCSD Medical Center head of cardiothoracic surgery who was in charge of the surgery, said Steveley’s recuperation was remarkable.

“It was very quick,” Jamieson said of Theresa’s recovery. “ . . . She hasn’t been on oxygen at all for the past week.”

Steveley said most cystic fibrosis patients require two to three weeks for an antibiotic therapy to clear the lungs of infection. “I went in for the same period and had a double-lung transplant. That’s pretty miraculous,” she said.

Theresa’s new lungs were transplanted without the use of a heart-lung machine, Jamieson said. The machine is normally employed in lung and heart transplants to oxygenate blood and relieve the heart’s blood outflow, functions performed by a healthy heart and pair of lungs. The technique employed by the medical center’s cardiothoracic transplant team rendered use of the machine unnecessary, Jamieson said.

“We did a left lung transplant while she was living off the right lung, and then we did a right lung transplant with her living off the newly transplanted left lung,” he said.

The team had to work quickly, Jamieson said, since a patient can live with one diseased or newly transplanted lung for only about 30 minutes. A heart-lung machine was on standby just in case, he said.

Cystic fibrosis, a genetic disorder that infects and damages the lungs, is the most common fatal genetic disease in the United States, according to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. About 1,400 new cases are diagnosed each year, usually within the first few years of life. The disorder causes the body to produce a thick mucous that clogs the lungs, causing persistent coughing, recurrent wheezing, frequent pneumonia, salty-tasting skin and excessive appetite but poor weight gain.

Thirty years ago, Anne Steveley told doctors at a military hospital in Japan that her daughter’s body secreted so much salt that it burned her lips to kiss the 1-year-old. The physicians told her she worried too much, she said.

One year later, the same doctors stopped shrugging off her complaints and informed her that her baby Theresa had been born with cystic fibrosis. There was very little known about the disease, they told her, but one thing was sure: There was no cure.

“Take her home and enjoy her,” Anne Steveley said she was told. “She will never live to see school.”

Thirty-one years later, there is still no cure for this genetic disorder, but a wave of recent lung transplant operations now offers hope for Steveley and others with cystic fibrosis, Jamieson said.

Steveley is only the 22nd cystic fibrosis patient in the world to undergo the surgery, but Jamieson said he believes the operation will become more common in the future. “It will open up a whole new field of lung operations for people with cystic fibrosis,” he said. ‘About six people are now on the medical center’s waiting list while donors are sought. The operation and hospital recuperation cost about $100,000, he said.

Steveley has survived the riskiest period--the first several weeks following surgery--but is not yet risk-free, Jamieson said. “She’ll need to take immunosuppressive drugs all her life to prevent rejection of the transplanted organs,” he said.

“The fact that she’s done so well makes us very optimistic about her future,” he said.

From her Hillcrest home, Steveley credited God, her organ donor, family and friends, church groups, the hospital staff and a positive attitude for her recovery. Balloons and a large, colorful ‘Welcome Home, Theresa’ sign were tied and taped to the front porch. A picture of St. Therese, for which she was named, hung on the living room wall.

“I want to specify the importance of the donors,” she said. “If it wasn’t for the donors, I wouldn’t be here right now.”

A lab assistant at a diagnostic, clinical testing manufacturer, she said she hoped to return to work by July.

Steveley’s determination and quick recovery did not surprise her mother. Anne Steveley credited Theresa’s positive attitude with carrying her through a long and risky surgery.

“You need to know my daughter,” she said. “She’s one dynamic woman.”

Melissa Steveley, 25, the youngest of Anne Steveley’s five daughters, was also diagnosed with cystic fibrosis. She said she has not yet considered having the same operation.

“Hopefully, by the time I need one, they’ll have a cure,” she said.