Treasures of Deep Spur Fight : Booty: Head of U.S. salvage firm squares off against Canadian government over rights to luxury steamer that sank in Lake Erie in 1852.

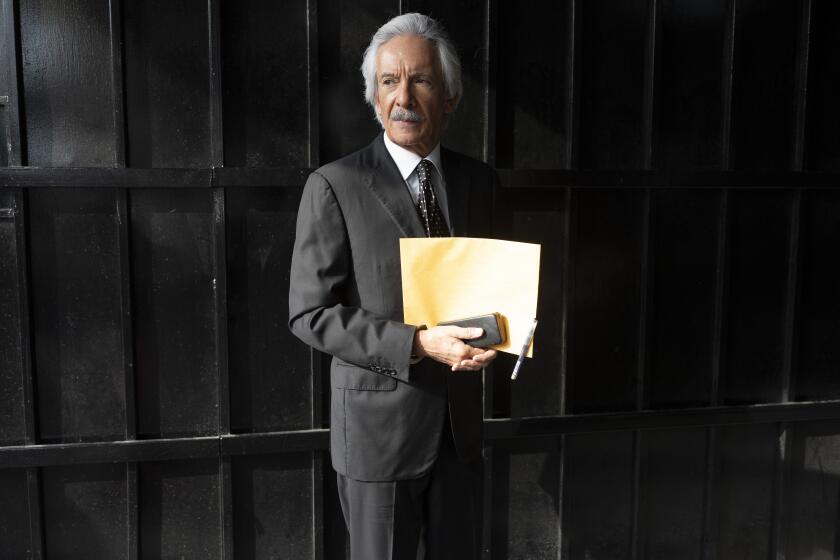

To hear treasure hunter Steven Morgan tell it, national pride--not to mention all that loot--is at stake in a rapidly escalating tiff with Canadian authorities over rights to a luxury steamship that sank nearly 140 years ago in the frigid waters of Lake Erie.

With characteristic fanfare, Morgan vowed Friday to fight efforts by Canada to block his San Pedro salvage company’s attempted recovery of the Atlantic, a 266-foot luxury steamer that sank in 1852 and may have millions of dollars worth of gold aboard.

“We’re not going to be kicked around,” Morgan said in an interview. “This is a U.S. vessel. . . . We own the ship and have a treaty protecting our rights to it.”

But officials in Ontario have a different opinion. Provincial police on Thursday issued arrest warrants for Morgan’s two divers and said they have orders to stop the salvaging project. Morgan and his company could face at least $250,000 in fines and one year in jail for removing archeological items without a license.

Citing cultural heritage laws, Ontario officials said that removing artifacts from the shipwreck constitutes an attack on their nation’s patrimony. The wreckage, they said, is a valuable archeological site that must be protected from scavengers.

Morgan, president of the Mar Dive Corp., rejected those arguments. His is a “responsible” salvage operation that only has the best interests of the ship at heart, he said.

“To allow her to lay there . . . on the bottom (of the lake) . . . and rot is doing no one a service,” Morgan said.

Ultimately, the matter is likely to be settled in court, where attorneys and experts will explore the depths of maritime law, international treaties and theories of ownership versus abandonment.

Last month, Morgan held a press conference in Los Angeles to trumpet his company’s discovery. He said he believes the vessel conceals at least $60 million in antique gold coins. Historians are skeptical of such a find, saying the ship’s principal safe was recovered shortly after the wreck. Morgan countered by saying that he believes there are additional safes.

Regardless of the potential booty, everyone seems to agree that study of the wreckage could provide a rare glimpse into 19th-Century life, when steamships regularly plied the Great Lakes as a main mode of transportation for the affluent ladies and gentlemen of the era.

The Atlantic, with side paddle wheels the size of three-story buildings, collided with a freighter in the middle of a summer’s night during a regularly scheduled voyage from Detroit to Buffalo, N.Y. Approximately half of the ship’s 600 passengers drowned as the elegant liner plunged to the muddy bed of Lake Erie.

Coming to rest finally six miles southwest of Long Point, Ontario, the ship’s contents are believed to be well-preserved because of the cold, clear water that entombs the steamer 160 feet below the lake’s surface.

Morgan maintains that his firm entered into a partnership two years ago with the vessel’s owner, Western Wrecking Co. of Ohio, and began salvaging small articles from the wreck shortly thereafter. Under a 1908 treaty between the governments of the United States and Canada, Morgan said, Mar Dive has complete claim to the Atlantic and is only required to notify Canadian authorities when the salvage has been completed.

Not so, said the Ontario Ministry of Culture and Communication. Under the 1974 Ontario Heritage Act, archeological exploration--which is what the Canadians regard Morgan’s people as doing--requires a special license.

Believing that Morgan’s divers did not have that license, Ontario police ordered their arrest. The case is still under investigation and additional charges may be brought against Morgan and the company.

At the crux of the matter, of course, is who retains rights to the Atlantic, and what the ill-fated vessel’s destiny should be.

“We feel we have a potential claim to the contents and the vessel,” said Armando de Peralta, spokesman for the culture and communication ministry. “We consider any vessel at the bottom of an Ontario lake bed for more than 100 years to be an object of antiquity and . . . important to Ontario’s cultural heritage.”

His government’s interest is primarily in preserving the wreckage for scientific and historical study, de Peralta said. Some experts have advised the ministry that removing the ship’s hull could be dangerous because portions of the wood might dissolve when exposed to air, he said.

“We don’t want to disturb the site,” de Peralta said. “We want to protect it from being looted. People are using the word ‘salvage’; that is not quite the word we are looking at.”

To say that the Atlantic might belong to Ontario is, well, downright un-American, Morgan argues. When it sank, he said, the Atlantic was U.S.-registered; its crew and passengers were largely U.S. citizens; it was on a regular route between U.S. cities, and was even contracted to carry the U.S. mail.

Morgan said the only reason the ship sits in Canadian waters is because it headed for the nearest shore--Long Point, Ontario--in a desperate attempt to save itself after it was hit.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.