Business Is on the Move--Is That Terrible?

Uh-oh. Reliable old Zero Corp., which makes electronics enclosures and aluminum luggage, is moving two of its operations and 460 jobs from Burbank to Salt Lake City.

Zero isn’t the only leak in the dike. In January, California Business magazine listed 40 companies moving operations out of state, and more will surely follow. Last November, a California Business Roundtable survey of 836 companies with more than 100 employees found that 14% plan to leave and 41% plan to expand elsewhere.

Is this bad? Probably. Should we worry? A little. Can we do anything about it? Well, not much.

The state’s business climate can surely be improved. California firms feel burdened by regulations and costs, and a 1990 study of manufacturing conditions by Grant Thornton, an accounting and consulting firm, ranked California 22nd among 29 significant manufacturing states.

But the movement of some manufacturers and other firms is probably inevitable for a single ironic reason: California’s economy is just too strong.

Consider why companies move. James Semradek of PHH Fantus, a leading relocation consultant, says California manufacturers are first and foremost concerned about environmental regulations.

But California’s environmental rules arise from its tremendous growth, which would be impossible if the economy weren’t so robust. More people and more business activity have meant more pollution and more alarm. Thus, regulation.

Another big factor in relocation is money. In the Roundtable survey, the two things rated as having the worst effect on business in the state were the costs of housing and labor.

But housing tends to cost less in places where you can’t make much money or probably wouldn’t live--say, Utica, N.Y. As people in the Northeast are beginning to discover, you start worrying when homes get cheap. High-priced housing is a consequence of California’s success.

Same for labor. High wages in the absence of unions imply scarcity and productivity and that people have money to buy things, which is why Southern California is a great retailing market.

So California has trouble competing in certain businesses. The Bureau of Labor Statistics says 1989 average annual pay in California was $24,921. That’s above the U.S. average of $22,567 but lower than New York’s $27,303. Now look at Arizona: $20,808. Utah was $19,362. New Mexico was a mere $18,667, 25% less than California.

The difference in housing costs is also large. In the latest survey by Coldwell-Banker, a 2,200-square-foot home in a good neighborhood cost $606,667 in Newport Beach, $370,000 in San Rafael and $203,750 in Riverside, but $131,975 in Reno and $122,800 in Salt Lake City.

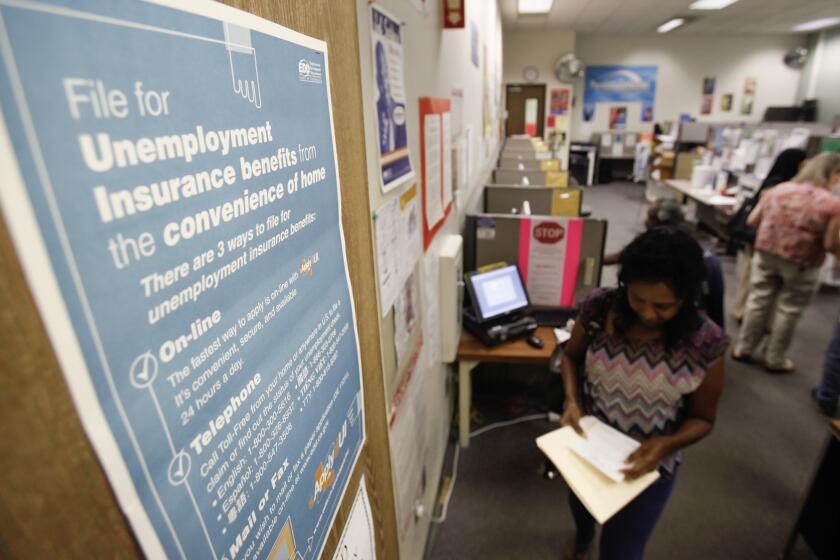

Like some California homeowners, some companies find themselves sitting on real estate so valuable that it pays to cash out. Other states make it easy with local recruitment offices, toll-free numbers and seductive ads.

What we have here is the marketplace working. Prices in California are sky-high. The state grows increasingly crowded. So some firms think about moving.

(General Motors’ plans to close its Van Nuys plant are in a different category, although it’s noteworthy that Honda and other new American car makers haven’t chosen California.)

If other states succeed in bringing in business, prices in them will rise. Regulations will accrete. California, meanwhile, might get more affordable. Our dizzying rate of growth--for many residents a paramount concern--might slow. And we’ll be more competitive.

Besides, it’s almost unseemly to complain now about the same restlessness and enterprise that made California so big and rich in the first place--the same spirit that brought the movie business and the Dodgers out from New York.

The state isn’t about to collapse. Now the world’s eighth-largest economy, it’s made jobs for millions of immigrants and for women who previously might have kept house. In 1940, 39% of the state’s 7 million residents worked. In 1990, it was 47%--of 29 million Californians.

Zero President Wilford D. Godbold Jr., who now heads a California Chamber of Commerce task force on keeping jobs in state, cites staggering workers’ compensation and health-care costs and a frustrating array of agencies and rules governing California business.

He’s right about a lot of this; by moving, Zero will save perhaps $5 million a year, and not just on wages. That’s why, although remote parts of California are almost as cheap as Utah, businesses leave anyway.

Their departure hurts. California has had a huge influx of relatively unskilled immigrants for whom such losses are tragic; Zero provided steady employment with health insurance. Without such companies, California could face a costly and painful mismatch between its work force and the jobs available.

Still, the challenge ahead won’t be figuring out how to keep some of the companies that want to move relatively low-skill operations elsewhere. The challenge instead will be twofold.

First, we need intelligent choices for collective prosperity. Assuming the law and the electorate tolerate a given level of pollution, do we use it up driving or manufacturing?

Second, California must remain the place to be for high-value enterprises. Education, skills and productivity will be crucial.