Fish Story Panned Out Though Grunion Didn’t Run

When the Chun family of Irvine decided to go grunion hunting at Doheny State Beach last week, probably the last thing they expected was to be ambushed by a reporter.

After all, it was 2 a.m. and drizzling. The lights from the ocean-view condominiums perched above the sea had long been turned off. The fluttering sea gulls seemed to be the only other life on the beach.

Jong Chun, 46, was startled when park ranger Doug Harding and I hopped out of a white pickup truck and headed toward him, his wife and two sons.

Harding, who carried a gun on his waist, aimed his flashlight in Chun’s direction, who was minding his own business, out for a night with the family hoping to catch the grunion running in the low surf.

I whipped out my notebook, and after exchanging the usual pleasantries, asked Chun whether he would mind being interviewed for a story on those who brave the cold night air to watch the grunion run.

He agreed, but the grunion would not cooperate. They didn’t run as scheduled and the hoped-for feature story on the wonders of nature never saw its day in the newspaper.

A reporter sometimes spends odd--and long--hours collecting information for a story that never materializes. But nevertheless, the reporting process itself can be fascinating, even if it doesn’t lead to a bylined piece in the next day’s paper.

Such was the case with my grunion hunt; I learned a lot about the grunion and their habits, even if I didn’t get up close and personal with the tiny fish.

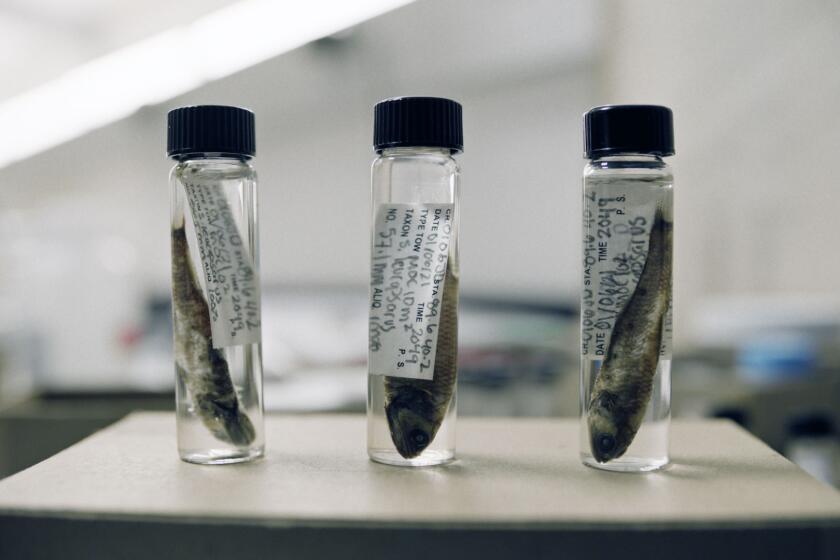

Before a Times photographer and I headed out on our grunion expedition, we had done our research on these small, sardine-shaped fish that leave the deep to spawn on beaches of the California coast.

The fish are supposed to run in four-night cycles from March to August. The spawning run always follows a full moon, when tides are at their highest.

Before heading to the shoreline, biologists say, schools of grunion send scouts to see if the coast is clear. The female grunion hit the beaches first, digging their tails in the wet sand and laying up to 3,000 eggs--each the size of a pinhead.

It takes two, three or four male grunion to fertilize the clutch of eggs. After that, the adult grunion catch the first wave back to sea, leaving the eggs hidden in the sand. About two weeks later, when the full-moon high tides return, the eggs are swept into the ocean where they quickly hatch--if they are not eaten by predators.

The grunion population is not threatened or endangered. Grunion stalkers by law can only use their hands to grab the fish, and grunion hunting is prohibited in April and May, the height of the mating season.

For the record, grunion do make tasty morsels. Most people deep fry them, but the Chuns say they prefer theirs Japanese tempura style. Others fancy grunion sushi, Chun said.

Over the years, dozens of grunion enthusiasts have gathered along sandy beaches from Santa Barbara south to northern Baja California to see how the slithery, silver grunion do their thing.

So I missed the grunion, but as in many stories reporters are called on to cover, there is always that little surprise that makes it all worthwhile. In this case, that surprise came in the form of Chun’s brother-in-law, 33-year-old Jason Hong of Orange. As it turns out, Hong was a junior high student in Seoul, South Korea, when he first saw a documentary about the grunion of California.

“I will always remember it,” he said. “It was called ‘The Silent World,’ and I remember how amazed I was about how they multiplied and survived. They’re almost like turtles.”

Hong credited the documentary with sparking his interest in pursuing a biology degree from Whittier College after he migrated to California nine years ago.

He now considers himself something of a grunion expert, and he passes on his wisdom to his nephews.

“You don’t want to get too excited when you see them come out of the water,” he said. “If you get excited, you’ll want to grab all at the same time and get none.”

On the night I met Hong he carried a fishing rod, and it was clear that he was going after bigger fish, using grunion as bait.

“Last year, I caught about 10 big halibut and bass using grunion bait,” he said.

But it was not Hong’s night, nor mine. The grunion, it turned out, did not appear.

“I’m disappointed but it’s just the way Mother Nature works,” Hong said.

And if I had not met Hong, the grunion story would have been one that got away.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.