CALIFORNIA ELECTIONS : Playing Fast With Loose Spending Rules : Campaign: O.C. incumbents among those more likely to give cash to other candidates than use it for their own ads.

California congressional candidates may be raising campaign funds at a record pace, but that doesn’t mean that all the money is being used to woo voters in their districts on Tuesday. Far from it.

Rep. Christopher Cox (R-Newport Beach), for example, flush with cash and facing only token opposition, handed out nearly $19,000 from his campaign coffers to other candidates and political organizations in and out of California. Rep. Robert K. Dornan (R-Garden Grove) spent $961,591 on national direct-mail solicitations to raise just more than $1 million. Dornan has used his high-powered national fund-raising operation to dissuade potential challengers and to build a network of conservative supporters.

Rep. Jerry Lewis (R-Redlands), the third-ranking Republican leader in the House, dipped into his campaign treasury to take his entire congressional staff on a two-day summer retreat in the Virginia countryside last year. Lewis called the “brainstorming” session “probably the best campaign dollars one might spend.” The total tab: $9,150.

And Rep. John T. Doolittle (R-Rocklin), one of the seven freshmen lawmakers who blew the whistle on abuses of House perks, used $9,206 in campaign funds to pay Pacific Storage to transport and store his personal belongings when he moved here from California in 1991.

The lawmakers have plenty of company among their California colleagues seeking reelection when it comes to dispensing campaign largess, according to a computer-assisted survey by The Times of the nearly $35 million spent by Golden State candidates as of Oct. 15.

Despite widespread anti-incumbent sentiment, many longtime lawmakers are still more likely to donate money to other candidates or charities, buy meals or plane tickets, or, in one instance, spring for prize-winning rabbits, than they are to pay for bumper stickers, mailings, radio ads or other conventional campaign trappings.

“You would expect that members would be more concerned about their ‘legitimate’ use of campaign funds in an era in which public anger and disgust at their perks of office are at an all-time high,” said Ellen Miller, executive director of the Center for Responsive Politics, a nonpartisan research group that supports campaign reform.

“If money is used in these ways for non-direct campaign expenses, it raises the costs of campaigns, and means they have to raise even more money from special interests.”

This pattern is hardly unique to California. Incumbents nationwide routinely take advantage of election laws that require only that campaign funds be used for a loosely defined “political purpose.”

In addition, House rules require that a member “shall expend no funds from his campaign account not attributable to bona fide campaign or political purposes.” Some of the expenditures of campaign funds for non-campaign purposes clearly accrue at least indirect political benefits.

Relying heavily on special-interest political action committees, most incumbents maintain permanent campaign operations to rake in contributions throughout the two-year election cycle--generally harvesting far more than their challengers could ever hope to raise.

Many lawmakers, usually those with overwhelming voter registration advantages, have not felt the need to dig too deeply into their campaign coffers to court voters.

Cox raised more than $395,476 between Jan. 1, 1991, and Oct. 15 of this year, but expended less than $11,000 on direct voter contact. He spent $61,000 on fund-raising, $151,000 on maintaining his campaign organization, and retired debts of more than $61,000 left over from earlier campaigns. On Oct. 15, Cox had $81,865 in campaign funds available in the bank.

In marked contrast, the two-term congressman’s Democratic opponent, John F. Anwiller, had raised less than $5,000, not even enough to require him to file campaign finance reports with the Federal Election Commission. In an interview, Cox argued that the bulk of his campaign money has gone for direct political purposes.

“The greater portion of the money was used either to eliminate debt or was applied to cash on hand. . . . The cash on hand is useful because you can turn it instantly into a mail piece, if you need to,” Cox said. “The fact that everyone who might challenge you knows you have a broad base of support and can defend yourself is very important. . . . One of the best ways in the world to campaign is to show some fund-raising prowess so you deter aggressors,” the congressman added. Among the other candidates to whom Cox’s campaign contributed were state Sen. Edward R. Royce, who is running for Congress in the Fullerton-based congressional district being vacated by retiring Rep. William E. Dannemeyer, and Assemblyman Tom McClintock, who his challenging Rep. Anthony Beilenson in a Los Angeles County race. Other Orange County incumbents facing stiffer primary or general election challenges have devoted more resources to contacting voters in their own districts.

Rep. Dana Rohrabacher (R-Huntington Beach), who defeated two high-profile challengers in the June 2 Republican primary, has spent about $103,000 on advertising and persuasion mail in the 1992 election cycle. But he invested only $35,500 in fund raising, compared to the $105,650 Rohrabacher spent on fund raising in the 1990 campaign. He is outspending his Democratic challenger, Patricia McCabe, by a margin of $269,000 to $14,000.

Rep. Ron Packard (R-Oceanside), who represents South County, channeled an unusually large amount to voter contact activities in the 1992 campaign, in which he faces his most spirited challenge in years.

Of the nearly $270,000 that Packard has spent in this election cycle, $141,370 paid for mailings to voters. He spent only $47,350 to maintain his campaign organization.

Packard is opposed by Democrat Mike Farber, a businessman who has spent nearly $48,000 of his $62,000 investment in the campaign on a sophisticated computer system. However, Farber has been able to muster just $750 for voter mail pieces.

The average incumbent has spent less than a quarter of his or her $462,032 total costs on campaign advertising, according to reports filed with the Federal Election Commission. Another 28% has paid for fund-raising expenses and 21% for overhead.

In contrast, California candidates in races for 16 open seats--half of which are hotly contested--have tended to channel far larger percentages of their campaign funds into directly soliciting voters.

The average candidate seeking an open seat has spent half of his or her $503,874 total on radio, television, mail and newspaper advertising. Only 8% has gone for fund-raising and 24% for overhead, including salaries, office rent, telephones and taxes. Royce, running in the open 39th District in Orange County, has spent nearly two-thirds of the $389,000 he has raised on direct voter contact, including $161,408 on persuasion mail. His Democratic opponent, Fullerton Council member Molly McClanahan, has spent slightly more than $50,000, including $21,000 on mail.

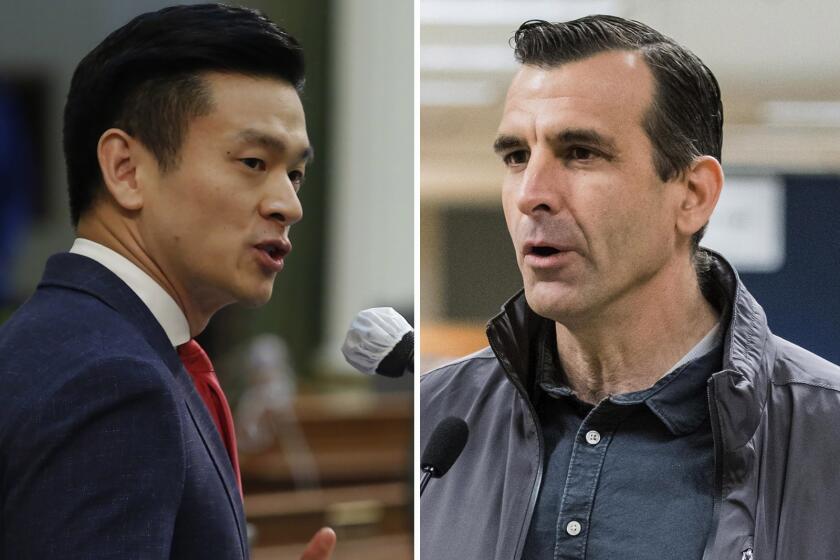

In the open 41st District, which straddles Orange, Los Angeles, and San Bernardino counties, Diamond Bar Mayor Jay C. Kim, the Republican, has spent more than $355,000 of his $546,000 campaign investment on mail and advertising, including ads run on cable television. Much of that money was spent to win a bruising party primary.

Kim’s Democratic opponent, Bob Baker, has not filed a report with the FEC, indicating he has raised less than $5,000.

In the Long Beach-based 38th District,Republican Steve Horn, a political science professor, has marshaled a stunning 86% of his $249,876 in expenditures for advertising and campaigning by relying on a distinctly home-grown approach.

Until recently, Horn has run the campaign out of his residence and his son’s Long Beach apartment, and has relied extensively on family and volunteers rather than consultants.

And not all incumbents enjoy the luxury of being able to take voters largely for granted this year. Reapportionment and public anger have thrust about a dozen members of the congressional delegation into uncomfortably tight races--and their spending patterns show it.

Rep. Vic Fazio (D-West Sacramento), the state’s most powerful member of Congress, who is fighting to stave off a 3rd District challenge from former Republican state Sen. H.L. (Bill) Richardson, has earmarked nearly half of his $1.2 million for radio and television advertising and persuasion mail. At the same time, Fazio spent $192,313 on expensive fund-raising events.

Even 10-term Rep. Carlos J. Moorhead (R-Glendale), who is not thought to be endangered, has stepped up his spending considerably after he was given a less solidly conservative district. Moorhead has spent $522,258--45% of it for direct campaigning--against under-financed Democrat Doug Kahn in the GOP-leaning 27th District that includes Burbank, Glendale and Pasadena.

Still, half the state’s incumbents who are seeking reelection have spent less than a third of their campaign funds directly trying to influence voters, including six who spent less than 10%. Conversely, only six have spent more than 50% on advertising and campaigning.

Rep. Tom Lantos (D-Burlingame), who has devoted only 14% of his funds to direct campaigning, donated $12,500 to the New Hampshire Democratic Party and made eight contributions totaling $15,500 to various candidates in that state. This included $5,000 to one contender and $2,500 each to two others in a Democratic gubernatorial primary and two $1,000 contributions to two mayoral aspirants in Nashua, N.H.

The Federal Election Commission is still reviewing a 1990 complaint filed by Lantos’ 1990 Republican opponent, accusing the California lawmaker of contributing $30,000 to the Democratic National Committee with the understanding that it would be used by the party in New Hampshire on his son-in-law’s behalf.

“I feel that when people give money to (a) political campaign they are doing so to get that person elected and I don’t think they should have that be spent elsewhere for other purposes,” said Glenn Tenney, a San Mateo Democrat who Lantos defeated in the June primary.

Repeated efforts to reach Lantos were unsuccessful.

Lewis, who is chairman of the House Republican Conference, said his two-day retreat “was a major effort to bring all of my Washington staff together far from the telephones, away from the office, where we could communicate with one another about the work we do . . . to coordinate and interrelate the work my conference does and my office does and how that may affect my constituency.”

His campaign paid $680 for rustic cabin lodging, $1,481 for catering and $6,990 for a firm that was hired to lead the discussion.

Lewis has also spent $23,731 of his campaign funds for meals, most at tony Washington restaurants. He said that he was entertaining visiting constituents, colleagues and lobbyists. He said that he wined and dined the lobbyists either “to tap them for information” or to get “to know those who influence others on giving money to campaigns.”

Doolittle, who faces a tough rematch with Democrat Patricia Malberg in the 4th District, has spent 51% of his funds on direct voter contact. But, the lawmaker, who was first elected to Congess in 1990, reported that his campaign paid for “storage and moving” costs on Nov. 11, 1991. An aide said this was to transport Doolittle’s personal belongings.

Doolittle could not be reached for comment.

Rep. Howard L. Berman (D-Panorama City), whose 26th District in the East San Fernando alley is safely Democratic, has given away $305,371, or 53% of his total spending. Most has gone to other Democratic candidates, including $152,251 to Californians. In contrast, he has spent only $22,014, or 4% of his total, directly contacting voters.

Rep. Henry A. Waxman (D-Los Angeles) has shown similar generosity, donating $296,303, 59% of his spending, to other candidates and causes. Berman and Waxman--who built a liberal political alliance in the Westside and San Fernando Valley partially through such campaign largess--gave a total of $140,000 to state Sen. Herschel Rosenthal (D-Los Angeles), a longtime ally who narrowly lost a June state Senate primary race to Assemblyman Tom Hayden (D-Santa Monica).

“There’s a benefit in a number of ways for me to help progressive Democrats,” said Waxman, who also raises funds and stumps for Democratic candidates. “First of all, they vote for or fight for the issues I care about. Secondly, when you help somebody, you develop a good working relationship with them.”

Critics of this practice say it is tantamount to trying to buy influence in the House.

Rep. Gary A. Condit (D-Ceres), who is unopposed Tuesday, has a 15-year tradition of buying the prize-winning rabbits at the Stanislaus County Fair Junior Live stock Auction. In 1991, Condit’s campaign paid $600 to take the longhairs off the auction block and return them to the children who raised them.

Fred Eiland, a spokesman for the Federal Election Commission said: “The law itself contains nothing that gives clear direction on what money can or cannot be spent for. In the past, the commission has always held that the (campaign) committees have broad latitude to determine how they spend their money.”

However, this year he said that a newly constituted commission split 3 to 3 over the question of whether a campaign committee could pay the candidate a salary.

Times staff writer Dwight Morris and researchers Mureille Gamache, Charlotte Huff and Michael Cheek contributed to this story.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.