Food Labels May Be More Honest, but Are the Ads?

Now that the Food and Drug Administration has taken a tough stand on health and nutritional claims that can be made on food labels, does that mean consumers will finally be getting honest information about the foods they eat?

Not necessarily, consumer activists say.

To be sure, the new food labels--which should start showing up on grocery shelves sometime in 1993--will make a big difference.

But food labels are not the only source of information for consumers.

Public-interest consumer groups assert that a huge loophole still exists that allows the food industry to persist in making false or misleading claims about their products: advertising.

Mark Green, consumer affairs commissioner for New York City, recently released a study that concluded that advertising continues to be rife with deceptive claims about food.

This discrepancy between the nutritional information that will soon appear on labels and what is still in the ads is “like giving consumers a drivers’ manual saying to hit the gas and the brake at the same time,” Green complains.

BACKGROUND: The reason for the informational gap is divided jurisdiction, consumer groups say. The FDA has the authority to regulate information on food labels, except for meat and poultry, which are regulated by the Department of Agriculture. Now, both agencies have finally agreed on what those labels should say.

The labels will provide uniform nutrition information, especially about fat, sodium, carbohydrates and protein. They should begin appearing on products in mid-1993 and are required to be on virtually all processed foods by May, 1994.

But neither agency has any power over advertising--claims made in newspapers, magazines and on television--which is solely the responsibility of the Federal Trade Commission.

Green calls the FTC the “Federal Trade Omission” because of what he and others say is its failure to crack down on food ads. His report, based on several months of scrutiny of magazine and television ads, listed numerous examples of sleight-of-hand practiced by food manufacturers.

Among them were instances of ads for highly sugared children’s cereals that emphasized the grain content but failed to be up front about the sweeteners; a vegetable juice that stressed its low calories but did not mention its high sodium content; and a promotion for a “low fat” salad dressing that showed “gobs of dressing poured on lettuce,” whereas only one tablespoon could be accurately described as low fat.

FTC officials counter that they are vigorously pursuing instances of deceptive advertising. Spokesman Don Elder defended his agency’s record, citing 11 cases that have been brought against food companies since Oct. 1, 1989.

Elder says deceptive food claims continue to be “a priority,” although he acknowledged that “with only a couple hundred attorneys, we have to be careful with our resources.”

Nevertheless, “we have brought a fair number of cases in recent years regarding what we allege were deceptive or misleading claims in food advertising,” Elder said. “It’s widely known we have an industrywide focus on diet, and already have brought action against several companies. We place a high priority on anything that puts a human life or health at risk.”

OUTLOOK: Consumer groups believe that the FTC’s approach--dealing on a case-by-case basis--is too time-consuming and cumbersome, and will barely make a dent in the problem.

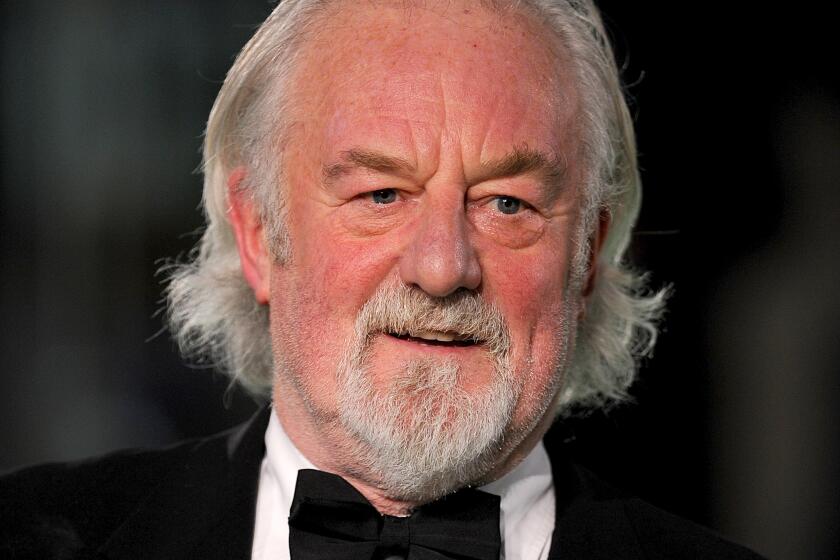

“It pales in comparison to what the FDA has done,” said Bruce Silverglade of the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a consumer group that deals in nutrition issues.

His group and others support legislation, first introduced in Congress in 1991 but never approved, that would require food advertising to be bound by the same standards, definitions and regulations as food labeling.